Beginning and Inciting

More than any other part of a story, the beginning has to grab the audience’ or reader’s attention.

In the beginning, before audience or readers are emotionally involved and concerned about the fates of the characters, the danger of them turning away from the story is greatest.

Now, there’s more to a beginning than the kick-off event. While being an attention grabber, the entire first section of a story also has to establish the following:

- Who the story is about

- What the story is about

- Where the story takes place

That sounds self-evident, but all the elements needed to answer those three points amount to an awful lot of information. And at this stage, the audience or readers are not yet patient or forgiving, because they are not yet emotionally hooked.

In this post we will:

- look at the who/what/where

- determine the three key events that the first section of a story must include

- provide a checklist of all the elements the first part of a story requires

Who/what/where

The “who” are your principal characters; that is, your protagonist(s) and most of the main characters. It is possible that one or two important characters burst into the story later, but in general a good story starts off by introducing the people that the audience is supposed to care about.

It is usually possible to sum up the “what” in a sentence or two by the end of the first section of a narrative. For example, “this is a story about aliens invading planet Earth”. “This story is about an old man who marries an unpleasant woman in order to get close to her daughter”.

“Where” refers not just to a geographical location, but to the world in which the story takes place, the setting. Is it a world of gritty noir realism, or a magical world of fantasy with laws of physics different from ours? Is it a courtroom drama in a specific city, or a rural romantic comedy set on a farm that could be anywhere? The “where” awakens genre expectations in the recipients, which the author has to be aware of in order to either satisfy or deliberately manipulate them. Most importantly, the rest of the story has to abide by the “rules” or “laws” of the world set up in the first section. A story that starts as one thing and ends as something quite different is rarely satisfying. There is an internal logic to stories that is set up in the first section – which is why this section is often referred to as “the set-up”.

With the “where” we have established the setting in which the story takes place. In the first section this is likely to be the ordinary world inhabited by the main characters.

What triggers a story is an event that happens to disturb this ordinary world.

First key event

The trigger event is often referred to as the inciting incident. It is the occurrence that causes something to happen, i.e. the story. It could be Luke seeing the message Princess Leia sent via R2-D2. It could be Humbert Humbert seeing Lolita for the first time. It could be the fox accosting the mouse in The Gruffalo.

This incident is often a coincidence, a random or chance event that does not arise out of any internal logic of the story. It usually creates a problem that the protagonist needs to solve, which is why structurally we refer to it as the external problem.

In any story, be it a simple one or a complicated one, be it old or new, be it an epic, a tragedy, or a short children’s story, there is likely to be one single identifiable event that get’s the story moving. And this inciting incident / external problem does not have to be the kick-off event (the kick-off is the very first event the storyteller has chosen to present to the audience).

Sometimes a story begins with the inciting incident. But often it does not. Leon shooting Holden in Blade Runner is the inciting incident, because this crime needs to be investigated and Deckard is chosen to do the job. Trinity running across the rooftops in Matrix is not the inciting incident. It is a spectacular kick-off event that grabs our attention, but what gets Neo’s story moving is the white rabbit tattoo.

An example

In Raiders Of The Lost Ark the inciting incident is decidedly unspectacular: when the men in suits come to the museum to get Indiana Jones’ opinion on what the Nazis are after in Egypt. What we saw beforehand, the opening sequence the film kicks off with, provides much information (we meet Indy, we understand this is an adventure story about a guy who raids artefacts, we glean that in his experience the magic surrounding such artefacts is mechanical and not supernatural, we meet his antagonist, – oh, and we learn that he hates snakes), but this self-enclosed opening sequence – like the opening of Matrix – does not contain the inciting incident.

So these two important story functions for the first section, the kick-off and the inciting incident, may actually be fulfilled by the same event, but do not have to be. Sometimes the inciting incident is merely reported in the first section, as part of the backstory, as in Oedipus Rex, where the murder of former King Laius is the event that, years later, incites the story Sophocles tells.

Second key event

If the first scene is in itself not much of a kick-off and the trigger event is not spectacular, then an emotional hook is necessary as early in the narrative as possible, so that the audience doesn’t wander off, change channel, or grab a different book. This emotional hook scene need not be impressive or action-packed, but it does need to elicit an emotional response from the audience.

The famous screenwriter William Goldman describes a scene in a detective movie he wrote, in which Paul Newmann in the first seconds of the film wakes up in his office bleary-eyed, picks a used coffee filter out of the dustbin and pours hot water through it, because he has no fresh coffee. This simple action tells a lot about the protagonist without any dialog, and makes the audience go “oooh yuch”. Emotional response achieved.

Third key event

Definitely separate from the inciting incident is the key event that follows as a consequence of the inciting incident. It is when the main character actually gets going into the story, the act of setting forth on the story journey.

Before the protagonist gets going, there is often some reluctance. And when the protagonist starts to get going, she or he may meet some sort of gatekeeper that she or he has to get past in order to begin the story journey. At any rate, the story is set up – the first section of the story ends – when the protagonist has committed to going on the story journey.

This important point in the narrative need not be loud or exciting, though it can be. It is when Deckard has agreed to take on the case (“No choice, huh?”). It is Neo choosing the red pill. It is Indiana Jones flying into the adventure. It is Humbert marrying the mother in Lolita, Luke discovering that his aunt and uncle have been killed by Imperial Stormtroopers, Jocasta mentioning the crossroads to Oedipus, and the mouse pretending to the fox that he will be meeting a Gruffalo.

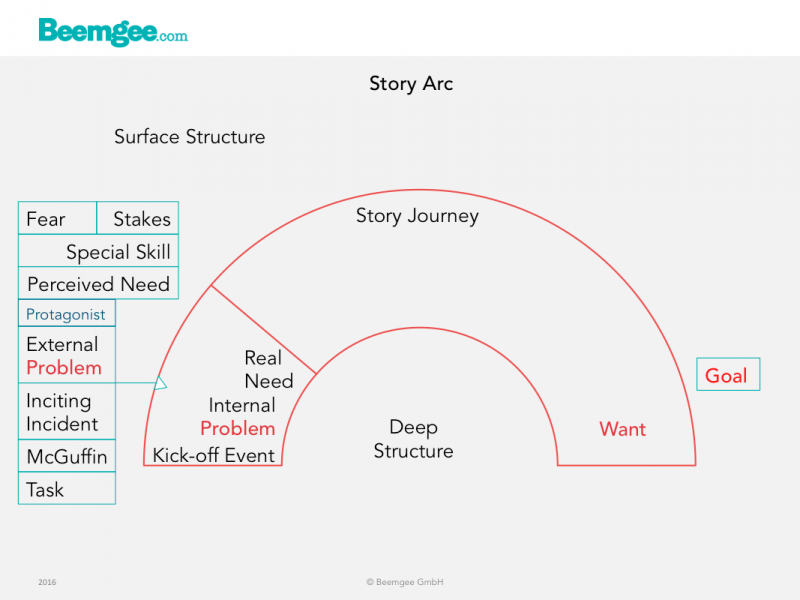

Once we are past this point, we are in the story proper. Everything the audience needs in order to understand the further developments – what the main character is after (want), how she or he intends to achieve that desire (goal), and what she or he is going to have to do to get there (task) – is likely to have been hinted at or referred to explicitly before this point already. The point locks the protagonist – and the audience or reader – into the story. It is what is often called the first major plot point.

So the first section of a story has to include three events that are fundamental to the story:

- an emotional hook

- the inciting incident / external problem

- setting forth on the story journey

The first two events might be combined. The emotional hook might be the inciting incident, but don’t rely on this. The inciting incident may possibly be shown in the very first scene, giving it the double role of being the kick-off event as well. A kick-off event might be emotionally charged enough to provide the hook, and if it isn’t, then an author should actively place a hook very soon after the first scene.

The setting forth is the first of the so-called major plot points, and marks the end of the beginning, because after that we know everything we need to know in order to enjoy the story. And ideally by then we care enough to want to find out how the story unfolds.

Feel free to refer to all of the above as Act 1, or as the set-up. In conventionally told stories, this usually takes up about a quarter of the entire narrative, conventional wisdom being that the recipient needs to be hooked fast and set off promptly on the story journey. But it does not always have to be that way. In the final story of Dubliners, for example, James Joyce devotes about forty pages to the set-up – the entire rest of the story needs only four pages more. Had he made the proportions more conventional, The Dead would have lost most of its astonishing emotional impact.

Checklist

This is a checklist for what needs to be set up in the first part of a story:

- The emotional engagement of the audience

- The setting or ordinary world of the story

- The external problem that triggers the story

- What the McGuffin is, if there is one

- What the protagonist wants

- What goal the protagonist sets her or himself

- The task that therefore presents itself

- What the protagonist believes she or he will need in order to complete the task

- Any special skills the protagonist might have – and require later in the story

- What’s at stake for the protagonist

- What the protagonist fears most – and will be confronted with later in the story

- The internal problem or shortcoming of the protagonist

- Most or all of the cast of characters

Read how the story goes on in The Middle Bit.

Related function in the Beemgee story development tool:

Structure Marker

Now compose your story. Click to open our free web-tool: