A story has a beginning, a middle, and an end. How to avoid the ‘saggy middle’.

The middle bit of a story is really the story proper. It is usually the longest section. It comes after the introduction of the main character(s) and the setting up of the context, that is the world of the story, as well as the problems and themes the story deals with.

At the end of the first section – prior to what we’re here calling ‘the middle bit’ –, the protagonist has decided to set off on the story journey. Obviously, this does not have to be physical journey through a particular geography, but it does mean that the main character is somehow entering into new and unfamiliar terrain. In this sense, every story is a ‘fish out of water’ story. The heroine must leave the comfort zone in order for the audience to feel interest in her plight.

Some authors jump right into this unfamiliar territory, showing the run up to it in flashbacks. Anita Brookner’s heroine Edith Hope has already arrived in the Hotel du Lac in the first sentence of the novel. Gradually the reasons for her stay here are revealed as the reader progresses through the novel.

Nonetheless, for an author, it may be advisable to create a marked threshold where the protagonist enters into the alien territory of the middle bit. The exploration and transversal of this territory is what on a plot level the middle bit is about, and it takes up the greater part of the story journey. (more…)

Today’s guest post is by author Stefan Emunds.

Today’s guest post is by author Stefan Emunds.

Stefan’s favorite genre is visionary fiction – stories that have an enlightenment dimension. Enlightenment and storytelling have interesting parallels, which prompted Stefan to write a book about storytelling – The Eight Crafts of Writing.

Get a glimpse of his approach to story craft in his article.

Art and Craft

Storytelling is both art and craft, authoring and writing, plotting and pantsing.

1.1 Art and Authoring

Art is creativity. Creativity requires receptivity to the Muse and its inspirations.

Inspirations arrive as thought-images, which writers put into words. How to turn thought-images into words and assemble those into a structured story with vivid characters and an engrossing world is a matter of craft and skill.

1.2 Craft and Writing

The literal meaning of Kung Fu is a discipline achieved through hard work and persistent practice. Writing is Kung Fu.

Craft gives form to inspirations. Forms limit. Writers love the artistic side of writing, less so crafting, in particular, Story Outline. Writers are prone to procrastinate crafting.

But no limitations, no story. No canvas, no painting. No net, no tennis.

Understanding the difference between freedom and dominion helps to appreciate the constraints of craft. Freedom is a means to an end. We want to be free to do something, for example, to write a book. That’s all there is to freedom. Dominion, on the other hand, is mastery of structure. (more…)

Universal storytelling principles behind the most successful movie series ever.

The sumptuous music of John Barry, the stunning set designs of Ken Adam, the directorial skills of Terence Young or Guy Hamilton, the innovative editing of Peter Hunt, the screen presence of Sean Connery, the zangy theme tune by Monty Norman, memorable actresses, spectacular stunts, and exotic location scouting – a fortunate convergence of individual talents built up the abiding popularity of Ian Fleming’s literary creation, the British MI6 agent James Bond.

Most writers don’t have access to such a talent pool, nor do most authors write action-packed spy capers. Also, 007 stories in particular seem so specific a category that authors might not consider that their own works have much in common with them. So one might be tempted to think that most writers can’t learn anything useful from James Bond.

Many people say there is a James Bond formula. Guy Hamilton, director of four of the early Bond movies, has said not. But there are certainly recurring scene types and structural elements that bear examination. A closer look reveals at least seven dramaturgical principles that any author could consider applying.

- The Kick-off Event

- The Real Reason for M

- The Real Reason for Q

- A Timely Death

- The Antagonist

- Revelation and Confrontation

- Humps

(more…)

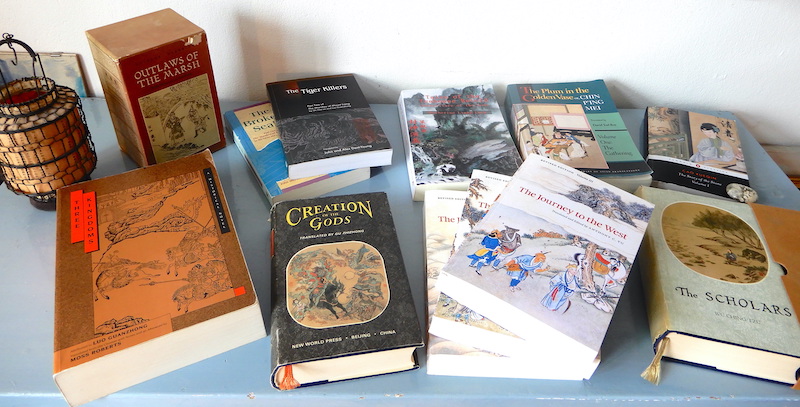

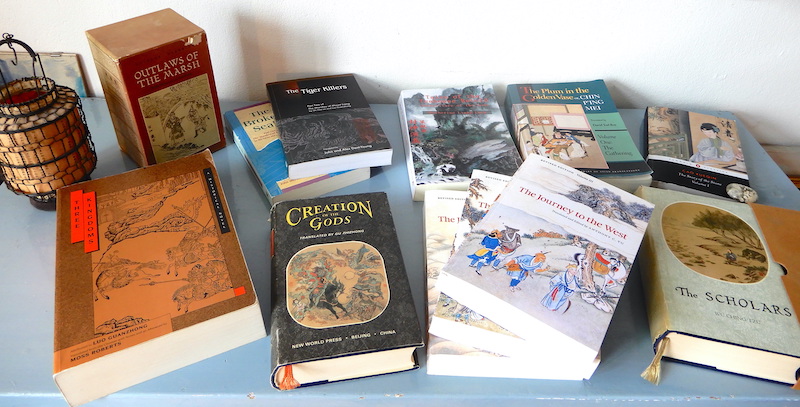

You have likely heard of The Divine Comedy, of Don Quixote, of Shakespeare – but have you heard of the Three Kingdoms? Of Sun Wukong? Of Cao Xueqin?

We asked ourselves, how are stories that had no contact with the western way of composing narratives different? Are the principles of storytelling really universal across cultures? Our idea was to find out by taking a look at classical Chinese literature. We discovered a number of interesting aspects to the Chinese way of telling stories, and have summarised them here.

In this post, we’ll tell you about the novels we read. Each was a revelation in its own way. The long-form novel came along quite suddenly in China just over 500 years ago. Generally recognised as the first great Chinese novel is Three Kingdoms, which appeared around 1494 CE. The most modern of the novels we’re considering here was published around 1760. That means we’re looking at Ming and Qing dynasty literature.

So which classical Chinese novels should you read? Here’s our list of favourites.

Our Top 7 Classical Chinese Novels

Nr 1

(more…)

Nothing should be more important to an author than how their story makes the audience feel.

As an author, consider carefully the emotional journey of the reader or viewer as they progress through your narrative.

The audience experiences a sequence of emotions when engaged in a narrative. So narrative structure is a vital aspect of storytelling. The story should be touching the audience emotionally during every scene. Furthermore, each new scene should evoke a new feeling in order to remain fresh and surprising.

The author’s job is to make the audience feel empathy with the characters quickly, so that an emotional response to the characters’ situation is possible. Only this can lead to physical reactions like accelerated heartbeat when the story gets exciting. We have to care.

This “capturing” of the audience, making the reader or viewer rapt and enthralled, requires authors to create events that will show who the characters are and how they react to the problems they must face. The audience is more likely to feel with the characters as the plot unfolds when the characters’ reactions to events reveal something about who they really are – and how they might be similar to us.

One Journey to Spellbind Them All

Here we present a loose pattern that we think probably fits for any type of story, whatever genre or medium, however “literary” or “commercial”. It’s not prescriptive, just a rough checklist of the stages in the emotional journey the audience tacitly expects when they let themselves in on a story. The emotions are in more or less the order they might be evoked by any narrative.

Curiosity

(more…)

Three sorts of opposition, and two things to remember.

Opposition causes conflict

For any character in a story, there may be opponents, not just for the protagonist. So while the protagonist-antagonism struggle may be at the forefront of the story, actually there is a whole system of opposing forces.

Let’s examine how characters in stories work against each other.

- Opposition can come from striving for the same or for opposite ends.

- Opponents can be antagonistic or incidental.

- There are two sorts of opponents, those from without, and those from within.

Same same or different?

An author might take each character at a time and arrange their opponents, which means characters who are either trying to get to the same thing first or whose success in attaining something else would thwart the character’s efforts.

In other words, the opposition (unless it arises by chance, see below) takes the form of either competition or threat. Competition for the same goal: Who will reach the South Pole first? Threat, because the goal of the opponent is opposed to the goal of the other figure: a nature reserve or a hotel complex. Imagine this for yourself using your own example: Your opponents strive for the same goal as you, and if your competitor wins, you get nothing. So your opponents are competing with you for the same goal, for example the same person. Or your opponent wants something completely different from you, and if he achieves that, it means you cannot get what you want. The success of the opponent is therefore a threat to your own well-being.

In either case, the opposition may be … (more…)

A plot arises out of the actions and interactions of the characters.

On the whole, you need at least two characters to create a plot. Add even more characters to the mix, and you’ll have possibilities for more than one plot.

Most stories consist of more than one plot. Each such plot is a self-contained storyline.

The Central Plot

Often there is a central plot and at least one subplot. The central plot is usually the one that arcs across the entire narrative, from the onset of the external problem (the “inciting incident” for one character) to its resolution. This is the plot that is at the(more…)

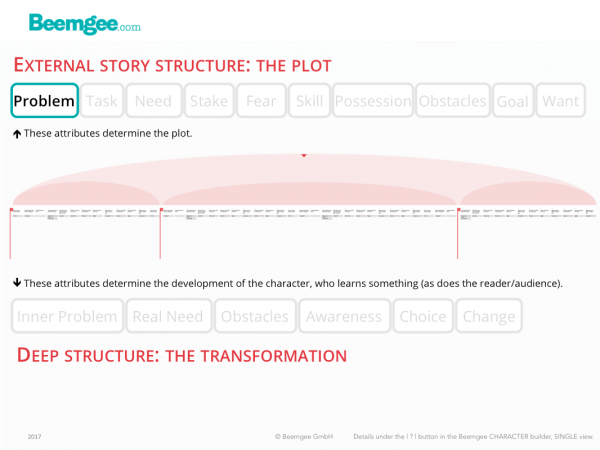

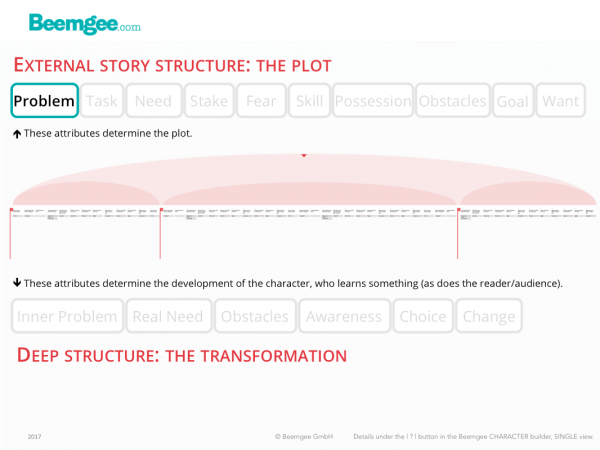

In stories, characters solve problems. This is the basic principle of story.

Problems come in all shapes and sizes. What’s more, in storytelling they come from within and without. The problems that come from within are hidden, internal, and it is quite possible for a character not to be aware of them. They are typically character flaws or shortcomings.

But they are not usually what gets the story going. Most stories begin with the protagonist being confronted with an external problem.

The external problem of the main character triggers the plot. It is shown to the audience as the incident which eventually incites the protagonist to action.

In some genres this is easy to see. In crime or mystery fiction, the external problem is almost by definition the crime or mystery that the protagonist has to deal with.(more…)

More than any other part of a story, the beginning has to grab the audience’ or reader’s attention.

In the beginning, before audience or readers are emotionally involved and concerned about the fates of the characters, the danger of them turning away from the story is greatest.

Now, there’s more to a beginning than the kick-off event. While being an attention grabber, the entire first section of a story also has to establish the following:

- Who the story is about

- What the story is about

- Where the story takes place

That sounds self-evident, but all the elements needed to answer those three points amount to an awful lot of information. And at this stage, the audience or readers are not yet patient or forgiving, because they are not yet emotionally hooked.

In this post we will:

- look at the who/what/where

- determine the three key events that the first section of a story must include

- provide a checklist of all the elements the first part of a story requires

Who/what/where

(more…)