When the bad guy makes the hero’s journey difficult.

Let’s say your hero or heroine is a falsely accused fugitive from the law. While on the run, every policeman or government agent is effectively an antagonistic obstacle. This is particularly the case if there is a specific character who represents the state and whose mission it is to catch the heroine. This detective or agent casts out the net to catch the fugitive, using all the instruments of the state at his or her disposal in order to actively thwart the heroine’s escape.

Or maybe your story is about a soldier behind enemy lines on a mission to find and destroy (or steal) the enemy’s new super weapon, or perhaps rescue an important person who has been captured. Any enemy soldiers the hero encounters are, of course, obstacles. One could say that they are external obstacles if they just happen to be there, like a patrol unit. But if there is on the enemy side a character who is aware of our hero’s approach and is actively seeking to stop him achieving his mission, then the soldiers and/or henchmen this character sends out to find the hero are not external obstacles but antagonistic obstacles.

As we have said before, this division into three classes of obstacles – internal, external, and antagonistic – is not cut and dried and need not be followed too strictly. But differentiating between the different kinds of obstacles a hero or heroine must face while designing and planning your story can lead to a more exciting plot, simply because you can disperse the obstacles systematically within the story journey and have all the different kinds of obstacle build up to a great crescendo at the climax. (more…)

How perceptive a character is of her surroundings may have dramaturgical relevance.

A character who is good at noticing small details may make a good spy or detective, so if you are developing a detective or spy you may want to give your character this ability. But whatever your character’s profession, stop at least once per scene and ask yourself,

What is a detail that only this character might notice?

Why is this important? Because their perceptions can make characters more interesting and vivid.

If a certain plot event hinges on a character perceiving some small detail or other, it may be a good idea to plant a foreshadowing moment long before the scene, to heighten the impact of the act of perception.

Furthermore, a character’s perception may influence how your audience understands and enjoys the entire story. How exactly depends on two important factors:

- narrator

- point of view

(more…)

Here at Beemgee, we’re into the thought behind the writing of stories more than the writing itself. So we’re all the more pleased that Writer.com approached us to talk about character development. While their speciality is AI-assisted text generation for companies, in their guest post, they have some good general advice on creating fictional characters. Thanks to Nicholas Rubright for this article. Nickolas is a digital marketing specialist and expert at Writer. In his free time, he enjoys playing guitar, writing music, and building cool things on the internet.

Here at Beemgee, we’re into the thought behind the writing of stories more than the writing itself. So we’re all the more pleased that Writer.com approached us to talk about character development. While their speciality is AI-assisted text generation for companies, in their guest post, they have some good general advice on creating fictional characters. Thanks to Nicholas Rubright for this article. Nickolas is a digital marketing specialist and expert at Writer. In his free time, he enjoys playing guitar, writing music, and building cool things on the internet.

Writing characters with whom readers can identify and empathize should be the goal of every writer, but it’s not a simple task.

To fully grasp a character’s motivations, desires, and anxieties, writers must dive deep into the character’s psyche. Character flaws and strengths work together to build a solid character.

But what is the most effective way to develop a character? And how can you establish a connection between your character’s dramatic decisions and the story itself?

Your characters are the heart and soul of your story. Thus, before you can write a single word, you must first understand your characters.

When it comes to character creation, you have several choices to make, and each choice affects the story in its own way. You must, however, choose what works best for your character.

While an unexpected detail can make the character more interesting, if it isn’t chosen carefully it can damage the character’s believability and ruin your reader’s immersion in your story.

Here are some guidelines and tricks to help you successfully create mouldable character templates for your story.

So, let’s dive in! (more…)

What a character might know that others don’t – including the audience

Some characters have secrets. We are not necessarily talking about their internal problem or the need that arises out of it (they may be aware of such a problem or not.) We are talking about information that makes a difference to the story once it is shared.

Character secrets are intimately bound to the scene type called a reveal (which does not necessarily have to entail a revelation).

In terms of story (or rather the dramaturgy of the story), if a character has a secret that is never revealed, the secret is irrelevant. Only if the secret is made known at some point in the narrative does it really exist as a component of the plot.

For authors, the main aspects of character secrets to control are:

- What plot event brings the secret about (this may be a backstory event)?

- How does the secret alter or determine the character’s decisions or behaviour?

- Does the character share the secret with another character at any point, and if so when (in which scene)?

- At what point in the narrative (in which scene) does the audience receive knowledge of this secret?

Who are you, really?

If it is so important the character has a secret, then, often, the secret becomes part of who this character is. Their role in the story, their identity within the story, is determined by their secret. So secrets are dramaturgically important. (more…)

Stories tend to show characters getting together.

Stories don’t get going until there are at least two characters.

That’s because the characters in themselves are not really what interests the audience. What the audience likes to experience is relationships.

At a fundamental level, there are only these three ways that people – or characters within a story – can interact with each other:

- they can cooperate

- they might oppose each other

- or they may get together

It is the complexities of these types of relationship that authors present to their audiences.

At least two of the three types of relationships are likely to be depicted in any story, cooperation and conflict. To make the story feel complete, authors especially of popular stories such as Hollywood movies often include the third type in the form of a love interest. (more…)

Three sorts of opposition, and two things to remember.

Opposition causes conflict

For any character in a story, there may be opponents, not just for the protagonist. So while the protagonist-antagonism struggle may be at the forefront of the story, actually there is a whole system of opposing forces.

Let’s examine how characters in stories work against each other.

- Opposition can come from striving for the same or for opposite ends.

- Opponents can be antagonistic or incidental.

- There are two sorts of opponents, those from without, and those from within.

Same same or different?

An author might take each character at a time and arrange their opponents, which means characters who are either trying to get to the same thing first or whose success in attaining something else would thwart the character’s efforts.

In other words, the opposition (unless it arises by chance, see below) takes the form of either competition or threat. Competition for the same goal: Who will reach the South Pole first? Threat, because the goal of the opponent is opposed to the goal of the other figure: a nature reserve or a hotel complex. Imagine this for yourself using your own example: Your opponents strive for the same goal as you, and if your competitor wins, you get nothing. So your opponents are competing with you for the same goal, for example the same person. Or your opponent wants something completely different from you, and if he achieves that, it means you cannot get what you want. The success of the opponent is therefore a threat to your own well-being.

In either case, the opposition may be … (more…)

Why The Hero Is Never Alone.

Allies Embody the Principle of Cooperation

Despite their complexity and diversity, there are essentially only three different kinds of human relationships.

That’s right, if you take a step back and try to categorize human interactions, you’ll find three distinct types. Biologists know this, because the principle applies to any species that lives in groups. Within the group, three types of behavior may be observed:

- individuals cooperate with each other

- individuals compete with each other

- individuals mate

Evolutionary biologists describe a spectrum of individual to group selection. Some animals will typically try to maximize their individual gain, as exhibited in behaviors such as taking the biggest share of food or the best space for offspring, without regard for other animals in the group. On the other hand, some species have evolved social organizations in which individuals may act purely for the group’s benefit rather than individual gain. Think of ants, bees, or termites.

Interestingly, on this spectrum between profit maximization and altruism, homo sapiens sit pretty much exactly in the middle. Humans are genetically programmed to selfishness, to seek what is perceived as best for oneself and one’s immediate family, and at the same time have a strong and innate instinctive and natural urge towards cooperation and social behavior – which ultimately also increases our survival chances.

Cooperation, neighborliness, charitable behavior, acts of kindness – even if they costs us, they generally make us feel better and they make life in the tribe, clan, or community so much easier. Mind you, we do like to look after number one. We’re not going to simply give up our salaries, our homes, our lifestyles. Our own needs and those of our families come first. Who is not aware of this dichotomy?

The pull in opposite directions between egoism and altruism is perhaps one of the specifics of human beings as a species that has caused us to evolve abstract thought processes as well as complex societal and cultural forms. It also sheds light on basic principles of storytelling such as conflict. (more…)

Where a character comes from may determine their values.

It is not always necessary to explain where a character comes from. Knowing their origin may not help the audience to understand a character.

But for some stories, origins can be vital.

As an example, take a contrast story like In The Heat Of The Night. Police Chief Bill Gillespie lives in the USA’s deep south and is a racist bigot. Such are his values, and for the purpose of this story also his internal problem. That he is a racist does not surprise the audience at all. It is completely credible given his origins. He comes from an area where, at the time at least, such bigotry was rife, and when the African American detective Virgil Tibbs turns up, their conflict is utterly plausible.

What we’re getting at here is that the values of a character have to be made plausible to the audience, which may be achieved by making the origins of that character explicit. In many stories, where a character comes from has to be fitting to what that character is like. Their origin produces the character’s values.

Setting, Origin, and Story World

Are we talking about setting? Well, only to an extent. (more…)

Archetypal Antagonism in Documentary Film and Fiction

by Amos Ponger of Mrs Wulf Story Consulting

Stories are intricate mechanisms

Documentary film is a powerful genre that draws much of its energy from the material of real-life action. Consuming documentaries, we as spectators often ignore the fact that documentaries, like fiction, are a constructed clockwork of storytelling. Since the digital revolution, the amounts of raw material for documentary productions have probably grown tenfold, shifting much of the dramaturgical construction work to the editing room. Dealing with hundreds of hours of material you may say that 90 percent of the editing work in documentary film is “finding the story“, discovering what your story is about.

One issue editors often encounter while working on the narratives of documentary films is that many directors tend to neglect the importance of understanding and designing their antagonist or their antagonistic powers, the Antagonism.

Sure, you love your protagonists. You identify with their strivings and journeys, and you as a storyteller have probably given a lot of thought to making them appealing to your audience, giving the audience someone they can identify with. Your protagonists may be an inspiration to you, or you may yourself strongly identify with them, you may share or appreciate some of their characteristics and values.

At the same time you have probably not given your Antagonist/m the same attention. Have you? (more…)

by Amos Ponger

A pledge to transformational storytelling

Working for over 20 years as an award winning film editor and story consultant, Amos Ponger studied film science, cultural sciences, art history and multidisciplinary art sciences at The FU Berlin, Humboldt University Berlin and the Tel Aviv University. He has a Master’s degree from the Steve Tisch School of Film in the Tel Aviv University, worked as an editing teacher in two Israeli film academies, is senior advisor to our story development tool Beemgee.com, and recently co-founded the story consulting service Mrs Wulf. Book his services directly here.

The Transformational Process of Creating a Great Story

We all know that creating a great story is a process that can sometimes take many months and even years to fulfill.

If you talk to professional writers they will probably tell you that they have complex relationships with these processes of writing. Involving dilemmas, fear and joy, suffering and excitement. And that these self-reflexive processes are also processes of self-exploration.

Yet many writers, scriptwriters, filmmakers tend to put a lot of energy into their external journey towards completing their story, focusing on drama, act structure, “cliff hanging”, while neglecting minding their own internal processes on their journey.

What many film and story editors encounter while working with directors and writers is that authors and directors tend to have a very strong drive. They endure months in writing solitude, or filming in deserts, storms, war zones, perhaps even putting themselves in danger in order to realize their artistic vision. Yet at the same time very often they have a remarkable incapability of explaining WHY they HAVE to do it, and can only do so in very vague terms. (more…)

Stories are driven by yearning.

In order to get somewhere, there has to be a current position and a destination. Stories fundamentally describe a change of state – things are different at the end of the story than at the beginning. Hence a story has a starting point and a final end point, a resolution.

But that’s not enough. There has to be fuel, energy to power the motion between the one position and the other. In stories, this driving force is the motivation of the characters.

Motivation is so important to storytelling that we are going to look at several aspects of it. We’ll break it down into what we call the wish, the want, and the goal, all of which are interlinked but also distinct from each other. Here in this post, we’ll deal with the wish.

A wish is inherent in the character from the beginning. We might call it a character want, as distinct from a plot want (which we deal with elsewhere).

Some examples: (more…)

In stories, the characters’ emotions are ultimately the sources of their actions, because motivations are ultimately based on emotions.

Determining the emotional core of a character in a story may lead to a clearer understanding of that character’s behaviour, i.e. their actions.

What we’re getting at here is essentially a premise for creating a story. We have noted that if you plonk a group of contrasting characters in a room – or story-world –, then a plot can emerge out of the arising conflicts of interest. If you’re designing a story, one approach is to create the contrasts between the characters (their essential differences of character) by giving each character a core trait or emotion. One character may be frivolous, another penny-pinching. One may be fearful, another cheeky.

You might object: Isn’t that a bit one-dimensional? Aren’t characters with just one core emotion flat?

Not necessarily. Focusing on one core emotion is not a cheap trick. It is as old as storytelling.

Classical Storytelling

Ancient(more…)

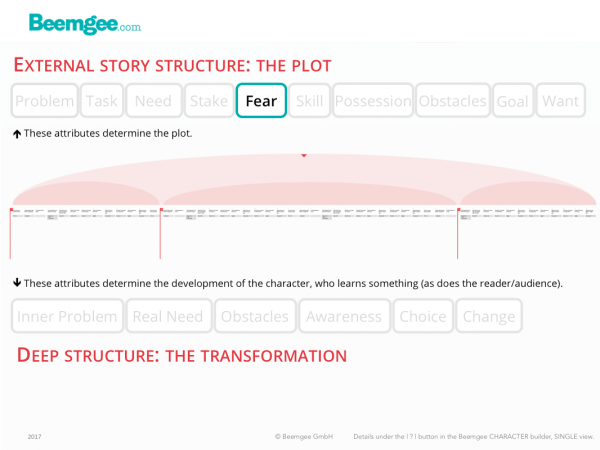

Certain universals are feared by almost everyone. Such as death.

If a character in a story has loved ones, losing them is an even stronger fear.

A story engages the audience or readers more strongly when there is something valuable at stake for the character, such as his or her own life or that of a loved one. So giving a character a universal fear is usually a good place to start.

Giving a character a specific fear to overcome requires this information to be placed early in the narrative. The fear is then faced at a crisis point in the story, usually the midpoint or the climax.

Characters can have specific fears. A fear which is specific to one character must be set(more…)

You’re on a boat, and you see somebody fall into the water. Which of the following two cases would cause you to react with stronger emotion?

- The water is four feet deep and you know that the guy who fell in is a good swimmer

- The water is four feet deep and the person who fell in is a three year old girl who can’t swim

Presumably your emotional reaction would be stronger if the child fell off the boat. Because you know that the child’s life is at stake. The first situation is not life-threatening, the only thing at stake is the dryness of the man’s clothes and his self-esteem.

The degree you care about events that happen to people, and to yourself, is directly related to what’s at stake. This applies as much to fictional characters as in the real world.

Hence it is immensely important for storytellers to(more…)

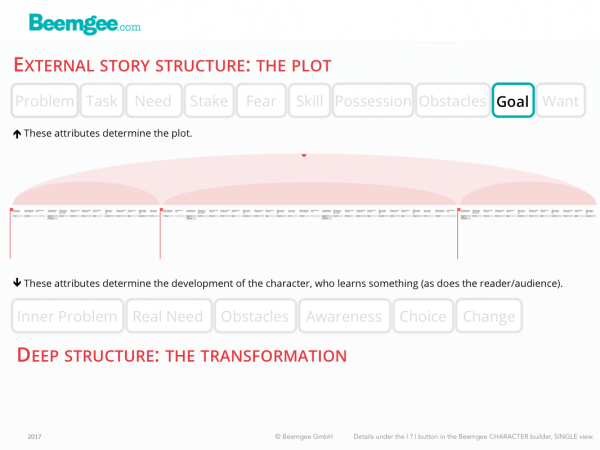

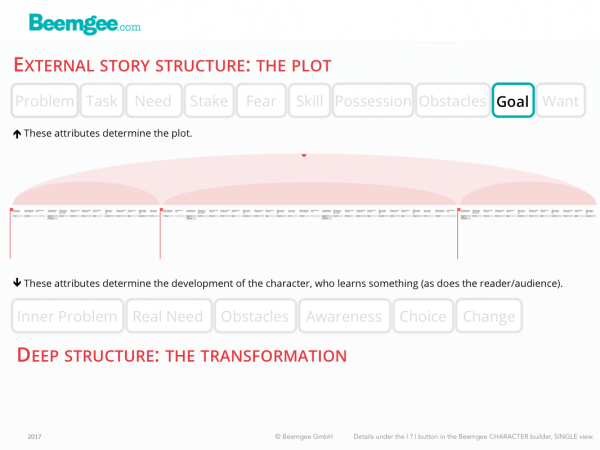

In a story, if the treasure is what the hero wants, then slaying the dragon is the goal.

The goal is what the character thinks will lead to the (satisfaction of the) want.

Since the treasure hoard has been there for ages, there must usually be some sort of trigger for the story to get started, i.e. for the character to want the hoard now, at the time the story begins. Often, an external problem creates such a trigger. It might supply a reason why the hero needs the hoard now, something more specific than just the general sense of wanting to be rich. Perhaps the hoard isn’t the reason at all. Perhaps there is a princess in distress, which certainly adds urgency to the matter. Either way, dealing with the dragon is the goal.

If somebody says the word “goal” to you, the image that springs to mind might have to do with the ends of a football pitch. The(more…)

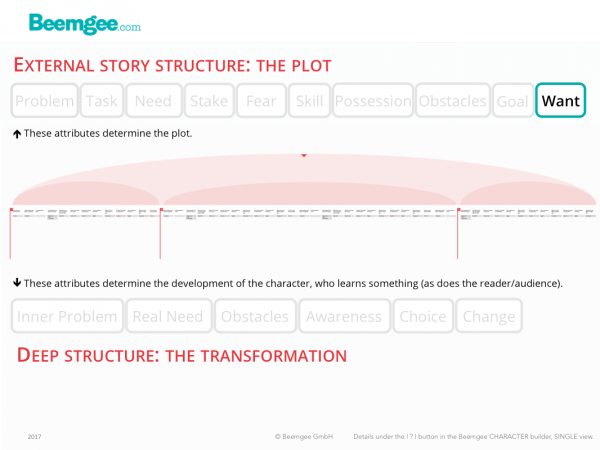

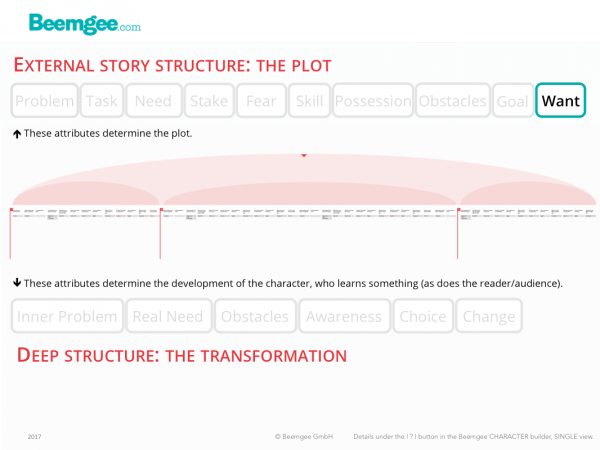

Stories are about people who want something.

We can distinguish between two different types of want:

- the wish, or character want

- the plot want

Marty McFly wishes to be a musician (character want). He also wants to get Back to the Future (plot want).

The wish or character want is a device which adds cohesion to the story, usually in the form of the set-up/pay-off. Marty is seen at the beginning of the film practicing the guitar; at the end of the film he plays at a concert. A character-inherent wish is a useful technique to make the character clearer to the audience, but it is not essential to composing a story.

Indispensable is what we have called the plot want. As a result of the external problem – the trigger event that sparks the chain of cause and effect which the bulk of the plot consists of –, the character feels an urge, which provides the motivation for the character’s actions in the story.

The want is the state for which the character strives, and is distinct from the goal.

In this post we’ll be talking about active vs. passive characters, motivation, the difference between a want and a goal, a couple of writer traps to avoid, and contradictory wants.

Active Characters

Characters have to be actively acting of their own volition. The want has to be urgent and strong enough for them to do things. If the want is missing or too weak, the character will lack motivation and appear passive. A passive character is usually not interesting enough to hold the audience’ or readers’ attention.

Why is this so?

Evolutionary explanations of stories attempt to shed light on the phenomenon. When characters react to events rather than cause them, they appear weak, as victims in a chaotic, uncontrolled world. Which means that there is not much we can learn from them. Humans try to see cause and effect in everything, not just in stories. And humans experience stories physically and emotionally (our hearts beat faster, our palms sweat), so there is really not much difference between how we experience a story and real life. Since we learn from experience, we instinctively prefer stories which provide us with experiences that benefit us in some way. In stories we vicariously experience or practice primarily social problem-solving, without suffering real-life consequences. We tend to learn more when we experience stories of self-motivated problem-solving.

Motivation

There is a good reason for that cliché about actors always asking about their motivation. It is motivation that prompts the characters in a story to do the things they do. Stories seem to work best not only when characters are active rather than passive, but often when they have comprehensible reasons for their activity.

The reason for what a character wants is usually comprehensible for the audience or reader because of the external problem. In simple terms, the character wants to solve the problem. Take the Cinderella story as an example. Her problem is that she is bound to the stepmother and her two nasty daughters.

In other words, the want is a vision the character has of his or her situation without the problem. Hence what the character wants is actually a particular state of being. Such a state might mean being in a position of wealth, power or respect, or being in a happily ever after relationship. Cinderella wants merely to be free of her involuntary servitude, if only for a little while.

This makes the want distinct from the goal, which is the specific gateway to the wanted state of being, as perceived by the character. A story usually sets up a goal the character needs to reach or attain in order to achieve the want. In Cinderella’s case, it is attending the ball.

So, a story has its characters pursue their wants. These different wants oppose each other, causing conflicts of interest. The conflicting wants make the characters active, and the audience/readers like stories about actions, that is, about characters who do things.

Sounds simple.

And yet frequently stories seem to mess up on this vital point.

Next to passive characters without a strong enough want, lack of clear motivation is a huge writer trap. It is possible to write a whole story full of characters who are reactive instead of active, or who do things of their own volition but without that volition being clearly recognisable to the audience/reader. It is perhaps even tempting to write stories like that, because they seem more lifelike. In real life, people do not necessarily have distinct goals. Often, our wants are vague and not clearly definable. What about writing a realistic story about a character with a general sense of dissatisfaction, who, like so many of us, has lost sight of any clear objective in life?

It’s doable, certainly. But the audience/readers will probably start to look for the specific want of such a character. They would probably begin to expect the story to be about this character’s search for a clear objective in life. That might be the want the audience would tacitly ascribe to the character.

And if the story does not bear such motivation out, the risk is significant. Because stories in which the audience does not understand what the characters want lack emotional impact.

Contradictory Wants

A way of adding psychological depth and emotional complexity to characters is to give them several and even contradictory wants. Gollum in Lord Of The Rings wants the ring. Yet a part of him also wants to give up the ring and help Frodo. Next to solving the case, Marty Hart in True Detective wants to be a good husband and family man, but he also wants affairs with other women. That’s three wants for one character.

A want is not merely a yearning, it is an expression of values. What a character desires shows the audience something about that character. In this sense, two contradictory wants provide the basis for a powerful scene of choice. At a crisis point, the character may face a dilemma and have to choose between two courses. Both might lead to some state the character desires, but these desires prove to be mutually exclusive. For the audience, which choice is the right one might be obvious – they will be rooting for the character to go one way. But for the character there may be a strong pull the other way. The final choice shows the character’s moral fibre – and often expresses the story’s theme.

When not to want

Is it really always absolutely necessary for every character to have a clearly defined want?

Not entirely. Because, of course, there are exceptions.

In certain cases, the author might deliberately obfuscate the why of a character’s actions in order to inject mystery. Not knowing something keeps the audience/reader guessing and turning the pages or not switching the channel. Usually this mystery is cleared up at some point. The audience tends to expect that. Which implies that even if the want was not made clear to the audience early in the story, it was there in the character nonetheless – and certainly the author was aware of it.

Injecting mystery by keeping character motivations hidden is not in itself a writer trap. But nearly. When tempted to use such a device, an author should at least consider if it would not actually be more interesting for the audience to know the character’s motivation.

Having said that, there are rare cases where a character’s motivation does remain unexplained. And those cases can be powerful. Especially when it’s a baddy we don’t understand.

Think of Iago in Shakespeare’s Othello, who is simply bad to the bone and we’ll never really know why. Shakespeare – deliberately, one presumes – gives no hint as to what Iago hopes to achieve by ruining Othello. Shakespeare might easily have given Iago some clearly understandable motivation, such as revenge of a past wrong, envy of Othello’s success, desire to usurp Othello’s position, lust for Desdemona. But he didn’t. And Iago is one of the most superb villains ever.

Another possible exception are (fiction) memoirs in the first person, such as David Copperfield, The Catcher in the Rye, Saul Bellow’s The Adventures of Augie March, or William Boyd’s Any Human Heart. In such stories, the effect of the narrator telling his or her own story creates a disparity between the time of the story told and the implicit future time of the act of telling. The narrator is relating a past from the perspective of an older self. This older self has reached a state of being which is different from that of the character being told about – the narrator is wiser than his or her younger self. This creates an effect for the reader: the reader wants to know how the character reach this older, wiser state. With this device, it is possible to make character wants less obvious or direct and still maintain an emotional drive to the story.

Perhaps the most interesting thing about a character’s want is how it stands in conflict with what that character really needs.

Related function in the Beemgee story development tool:

Character Developer

Click to open a new story project:

Action is character.

So the old storytelling adage. What does that mean, exactly?

In this post, we’ll consider:

- The central or pivotal action – the midpoint

- Actions – what the character does

- Reluctance

- Need

- Character and Archetype

The central or pivotal action – the midpoint

More or less explicitly, the main character of a story is likely to have some sort of task to complete. The task is generally the verb to the noun of the goal – rescue the princess, steal the diamond. The character thinks that by achieving the goal, he or she will get what they want, which is typically a state free of a problem the character is posed at the beginning of the story.

The action is what, specifically, the character does in order to achieve the goal (rescue the princess, steal the diamond). In many cases, this action takes place in a central scene. Central not only in importance, but central in the sense of being in the middle.

Let’s look at some examples. (more…)

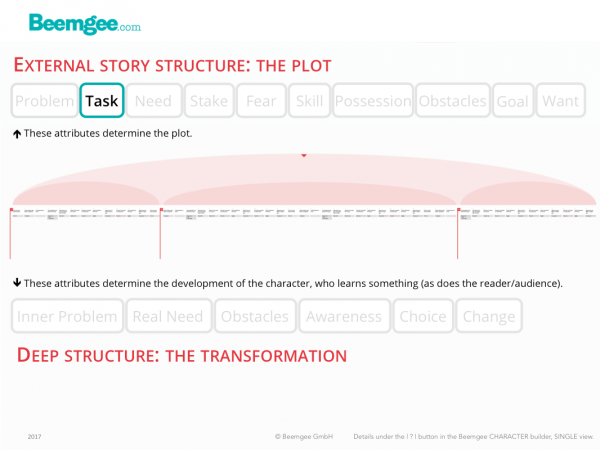

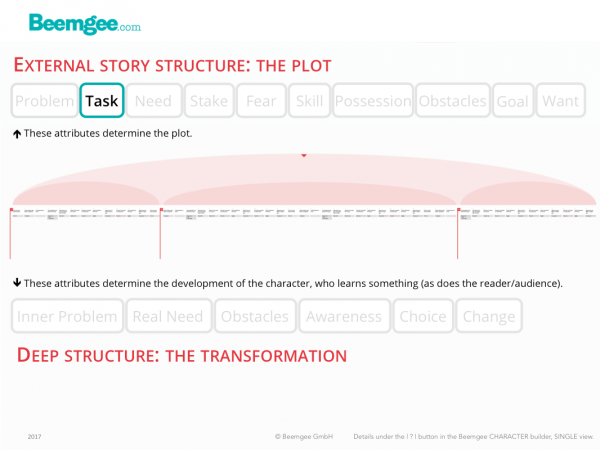

In most stories, the protagonist has something to do.

The task is the more or less explicitly defined mission a character sets out on in order to reach the goal and thereby solve the external problem.

Many of the major characters in a story will have something to do, which may result in them getting in each other’s way.

Task as Function

In a story, more or less everyone has a task. What characters do in a story defines them and determines their roles and narrative functions in the story. In this sense, it is an antagonist’s task to get in the way of the protagonist; an ally’s task is to help the protagonist; a mentor’s task is to advise the protagonist and set them on their way.

But while all that is true, it isn’t really what we mean by task.

Task as Action

The characters’ actions make them who they are. To define a character’s task is to state clearly what that character has to achieve in the story. It is the action that leads to(more…)

In storytelling, a character’s convictions and beliefs determine his or her choice of actions – at least in his or her conscious mind.

Convictions and beliefs are effectively values put into words. They lead to a rationalised intellectual stance and can be the basis for lifechoices and actions. A set of beliefs or convictions is the articulated version of a character’s values or emotional stance.

Consider story’s predisposition for cause and effect. If we understand the belief-system or intellectual stance as the effect, the value-set or emotional stance is the cause. Now, it may be nit-picking to make the distinction between felt values and stated beliefs. But then again, it might be quite helpful to see by what line of reasoning a character justifies his or her behaviour.

The effect can be powerful when there is a discrepancy (i.e. conflict) between what the character thinks is the reason for his or her actions and the real reason. When the audience or readers see that the words and thoughts of a character do not match with what that character is actually motivated by, the irony can be a satisfying story experience.

The Want as Beliefs, the Need as Values

(more…)

A character in a story has values and passions. In short, an emotional stance. It’s this bundle of feelings that make the character a character.

By emotional stance we mean a value-set. This is particularly important when one considers that often stories show value-sets in conflict. The protagonist and in particular the protagonist’s journey to recognition and change may represent certain values. These will be in direct contrast to the antagonist’s values. The theme of the story presents one value-set as preferable over the other.

In many stories, the protagonist starts out with a value-set that is warped or flawed. Their real need is to become aware that their value-set is harmful or negative, probably ultimately selfish, and find a way to gain new values that are more social, cooperative and selfless. For the purpose of such a story, the values are initially expressed in the internal problem and by the end have gone through a change.

Values do not emerge in a vacuum, they are instilled by environment or culture. Stories exhibit cause and effect, and the values of each of the characters are no exception. The audience looks for the causes of a character’s emotional stance. By the very nature of emotions and values, their causes can be hard to pinpoint – while at the same time being somewhat obvious. In stories, at least.

Furthermore, values are emotional and therefore exist before they are articulated. A character becomes conscious of a value-set in the form of a system of beliefs. The beliefs are articulated by the character as convictions, and are determined by inner values. In some cases, the stated beliefs may actually be in conflict with the character’s deeper values, of which the character may not be entirely aware. Values tend to feel right to the individual, though they may actually be wrong for the larger community or society.

A character’s values have to be plausible to the audience, which may be achieved for instance giving the characters appropriate social backgrounds or origins and making these explicit. In many stories, a character’s upbringing or their origin is named or described in order to explain their emotional stance.

Alternatively, values may be caused by certain specific events in the history or background of a character, conveyed as backstory in the narrative. A particular circumstance, possibly a trauma, leads the character to feel a certain way about life and the world.

Character Values in Historical Stories

In historical stories the time-setting is particularly challenging in terms of the emotional stance of the characters. Much popular historical fiction may justly be termed anachronistic in that it has characters – especially female protagonists! – exhibiting values and beliefs which do not fit into the time. For example: In the Middle Ages, the advent of humanism had not occurred yet. There had been no Renaissance, no Descartes, no Kant, no French Revolution and no American Constitution. Where is a character in the Middle Ages supposed to get ideas, values and convictions from that today we take for granted? Ideas about inalienable rights such as liberty and equality or concepts such as individualism. People in the past had different values and belief systems from people today, and it is almost impossible to put ourselves in their shoes. Historical fiction that does not at least implicitly deal with this challenging issue is more likely to be clichéd and trivial.

Which does not mean that trivial historical stories can’t be wildly entertaining with strong emotional impact. After all, modern stories address the audience of today. It means simply that an author usually has some sort of attitude to the issue.

Photo by Wonderlane on Unsplash

Related function in the Beemgee story development tool:

Character Developer

Already using the author tool? If not, try it here:

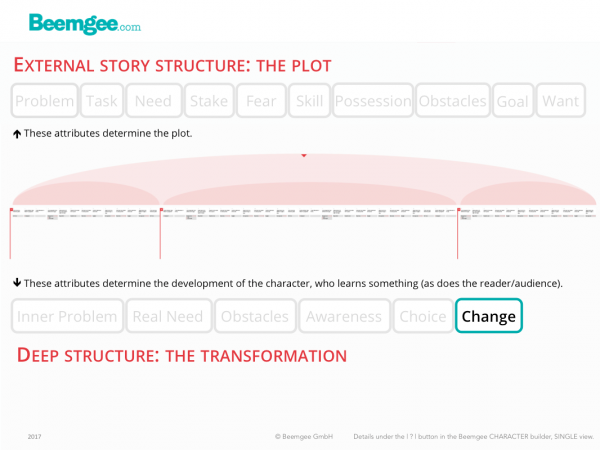

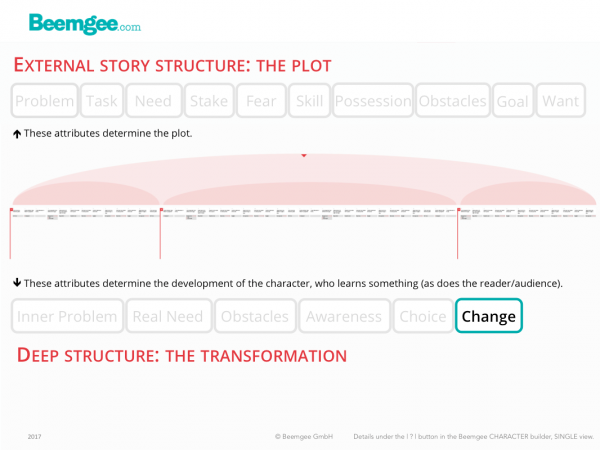

If there is one thing that ALL stories have in common, it is change.

A story, pretty much by definition, describes a change. Indeed, every single scene does.

Within a story, what changes?

At the very least,

- one of the characters, usually the protagonist

- often other characters too

- sometimes the whole story-world

- who understands what – the perception of what is true or valuable

1 – The protagonist changes

We have said before that a protagonist is usually wiser at the end of the story than at the beginning. We have seen that this has something to do with the want, which – whether the character achieves it or not – is usually only attainable by causing a change. Often the change involves the character’s solving the internal problem, so the change takes place within the character. This involves the recognition of the necessity for change, i.e. the acceptance of the real need, and the struggle to achieve it. So all the incidents and events in the plot, the hindrances and obstacles the characters deal with, are in themselves not so very interesting. What interests the audience more is how these events and obstacles change the character.

Having said that, a story may well show no more change than the solving of an external problem. A story world is disturbed, but at the end returns to a similar state. For instance in a detective story, where the crime is solved but the protagonist does not really develop.

2 – Several characters change

Characters don’t change in a vacuum. They learn through interactions with each other. Relationships cause change. In many stories, subplots will tell of the characters that surround the protagonist, and their changes and developments may well cast light on various aspects of the story’s theme. Or perhaps the story is an ensemble piece, where it is not easy (or even necessary) to identify a main protagonist. Or it is a romance, or buddy-story, which apparently has two main characters. Whichever – some level of change usually occurs in all the main characters as a result of how they interact with each other.

There is, by the way, one often neglected archetype who also typically changes. This role is sometimes referred to as foil. We call it the role of the contrastor. The contrastor mirrors and contrasts the protagonist, like Han Solo to Luke Skywalker in Star Wars or the mother to the boy in Boyhood.

3 – The whole world changes

Quite possibly, the entire story-world may be different by the end of the story than it was at the beginning. Story-world as a concept refers to the scope of the world presented in the story, so if the field of action of the characters is small, the story-world is small too. If the story is an epic, the story-world will be big, a version of an entire world.

As an aside on this last point, consider the classical genres. Epics – again, almost by definition – describe a change in a whole world. In a way, so does tragedy, for at the end of the tragedy the world will have lost one or more of its population, since tragedy deals with the change from life to death.

Comedy seeks to describe a different fundamental change in the story-world. The typical structure of comedy, whether we are talking about Aristophanes or modern TV sitcoms, has a stable situation at the beginning which is disturbed by some event or problem. The disturbance causes first a lot of messy but generally non-life-threatening chaos which is resolved by a return to the original undisturbed situation. Even if the main characters end up married, for example, the story-world is brought back to its stable state.

The very serious point of comedy is to demonstrate a fundamental truth: the cyclical nature of change in the universe. Spring always returns, no matter how bleak the winter. Day always comes, no matter how dark the night. Change does not have to be final. Change can be cyclical. Change is life.

4 – The Perception of Truth

The most fundamental change that stories tend to describe is one of recognition of truth. What is not known at the beginning of the story is recognised and thus becomes known at the end. This is obvious in crime stories, but holds true for almost all other stories too. The story therefore amounts to an act of learning. Often the learning curve is observable in the protagonist, who tends to be wiser at the end than at the beginning.

But the point is really that the recipient, the reader or viewer, is actually the one doing the learning – through experiencing the story.

The audience changes.

At least, that’s the general idea. The story provides a physical, emotional and intellectual experience – physical when your heart beats faster or your palms sweat, emotional when you feel for the characters, and perhaps intellectual too if the story gives you pause for thought. If the story achieves none of these responses, then it has failed. An experience, again pretty much by definition, changes you. We learn through experience; so if you have changed, chances are it’s because you have learnt something.

Hence it is not only within the story that a change takes place. It takes place outside of the story as well, in the recipient.

Within some stories one may argue that no real change occurs – Alice does not obviously change due to her experience in Wonderland. But the reader has been taken on a wild journey, and the experience is likely to have left some sort of mark.

How does a story provide an experience?

By allowing the recipient, the audience or reader, to understand and feel change and transformation throughout the story. Every scene describes a change. The entire narrative shows a difference between the “before and after”. Stories have a tendency to symmetry: The beginning of the story makes clear what the state of the protagonist or the story world is before the story journey commences, and the end of the story has a corresponding scene or event that shows what the state is after.

For the author, then, the task is to clearly know the state of things for the protagonist, the cast of characters, the story world, and the audience at the end of the tale, and the state of things at the beginning of the tale. The greater the contrast, the better. Once these two points of reference are known, the author works out the many steps needed to get the protagonist, the cast of characters, the story world, and the audience from one state to the other.

There is a paradox here. The change that occurs is also an expression of new equilibrium. At a very basic level, story structure can be described as follows:

- an external problem (a change in the ordinary world of the protagonist) disturbs the equilibrium of the initial situation

- the disturbance is explored, a struggle ensues in which obstacles must be overcome

- the problem is understood and dealt with, creating a new equilibrium or resolution

So change is all-pervasive in stories, within them in the form of character development, and without in the form of audience understanding. And that is not even to consider the transformational power of telling a story, when the act of telling the story brings about change in the author.

Read here how change is important for every single scene, though we prefer to call them plot events.

Related function in the Beemgee story development tool:

Character Developer

Not developing your story yet? Click here:

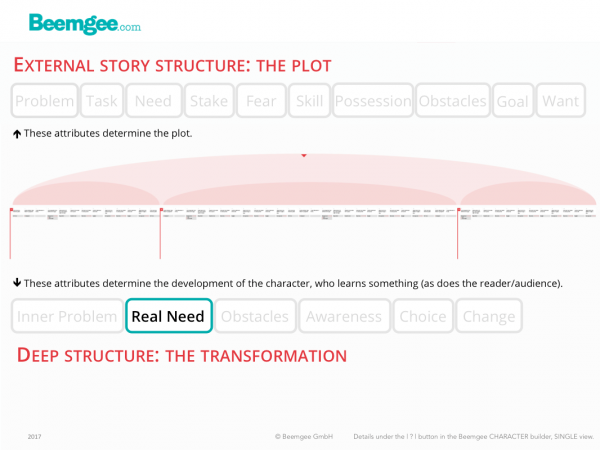

In most stories, what a character really needs is growth.

Characters display flaws or shortcomings near the beginning of the story as well as wants. What they really need to do in order to achieve what they want is likely to be something they need to become aware of first.

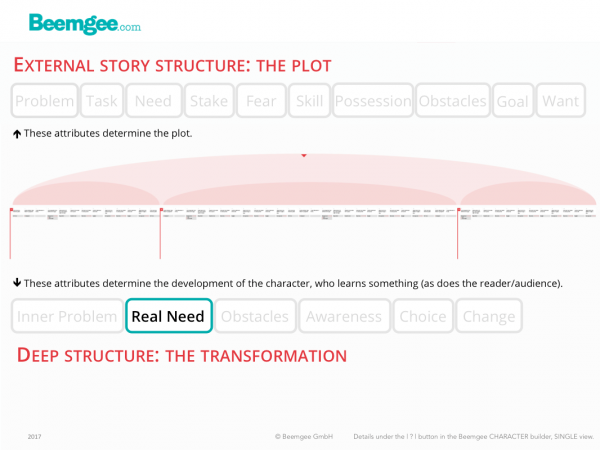

The real need relates to the internal problem in the same way the perceived need relates to the external problem. The character has some sort of dysfunction that really needs to be repaired.

That means the audience or reader may become aware of a character’s real need long before the character does. Most stories are about learning, and learning entails the uncovering of something previously unknown. So the real need of a character is to uncover the internal problem, to become aware of their flaw.

A character may be unaware of their real need because they are suppressing a secret from their past. Something they did (better than something that happened to them) causes shame or guilt and they therefore hide it from themselves. To get over this, they must achieve some sort of healing. The trick is to dramatise such inner conflict through plot events.

To recap: The usual mode in storytelling has a character consciously responding to an external problem with a want, a goal, and a number of perceived needs. Unconsciously, that character may well have a character trait that amounts to an internal problem, out of which arises that character’s real need – i.e. to solve the internal problem.

So if a character is selfish, the real need is to learn selflessness. If the character is overly proud, then he or she needs to gain some humility. In the movie Chef, the father neglects his son emotionally – his real need is to learn to involve the child in his own life. The audience sees this way before the Chef does.

Even stories in which the external problem provides the entertainment – and with that the raison d’être of the story – may profit from(more…)

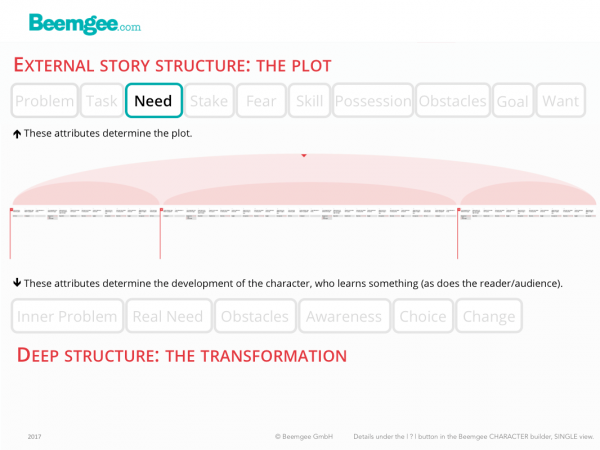

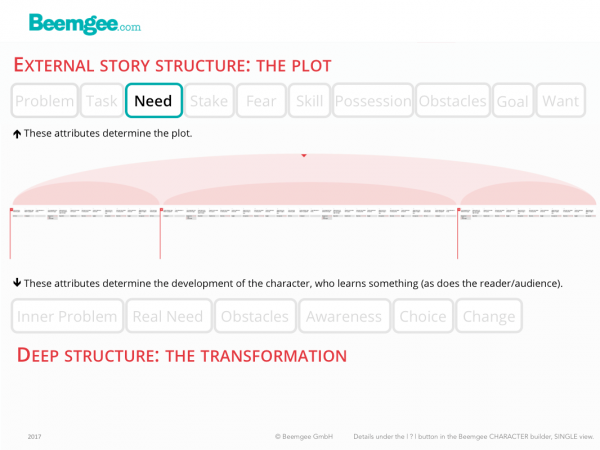

A character with a goal needs to do something in order to reach it.

The outward needs of a character – things she needs to acquire or achieve in order to reach the goal – divide the story journey into stages.

In storytelling, characters usually know they have a problem and there is usually something they want. They tend to set themselves a goal which they believe will solve their problem and get them what they want.

In order to get to the goal, the character will need something. Some examples: If the goal is a place, a means of transportation is necessary to get there. If we can’t rob the bank alone, we’ll have to persuade some allies to join our heist. If the goal is defeating a dragon, then some weapons would be helpful. If magic is needed, we’ll have to visit the magician to pick some up.

While the perceived need might be an object or a person, it usually requires an action. We’ll need a car, so do we buy one or steal one? We’ll need a sword, so do we pull one out of a stone or go to the blacksmith? If we need help, who do we ask and how do we talk them into joining us? We’ll need magic, but how do we find a magician? Ask an elf or go to the oracle for advice?

So, once the goal is set, a vision of the way to reach it opens up to the protagonist – and with that to the audience/reader. At the very least, the first step of the way presents itself. All this is what the character is conscious of.

In other words, the character forms a plan.

The plan is communicated more or less explicitly to the audience. The anticipation of how things will not go quite according to plan is part of the pleasure. There must always be surprises in store for the characters as well as for the audience.

Stages and Obstacles

The perceived needs are (more…)

What’s the problem? Does the character know?

In storytelling, discrepancy between a character’s awareness and the awareness-levels of others is one of the most powerful devices an author can use. “Others” refers here not just to other characters, but to the narrator and – most significantly – to the audience/reader.

Let’s sum up potential differences in knowledge or awareness:

- A character’s awareness of his or her own internal problem or motivation

- A difference between one character’s knowledge of what’s going on and another’s

- The narrator knows more about what is going on than the character

- The audience/reader knows more than the character – dramatic irony

In this post, we’ll concentrate on the first point: Awareness of the internal problem. We’ll break that down into

- Becoming Aware – the importance of the revelation

- The Story Journey – and where to place the revelation

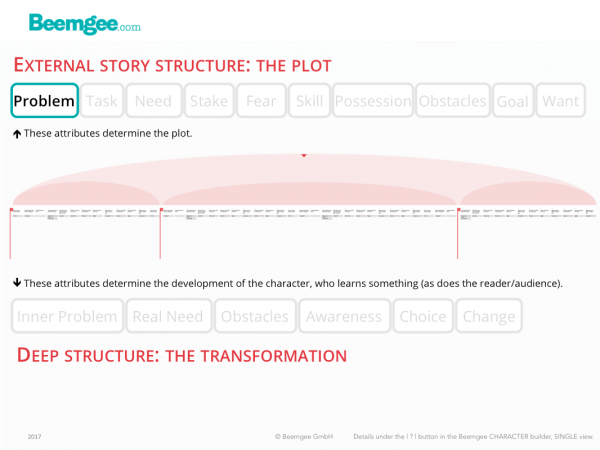

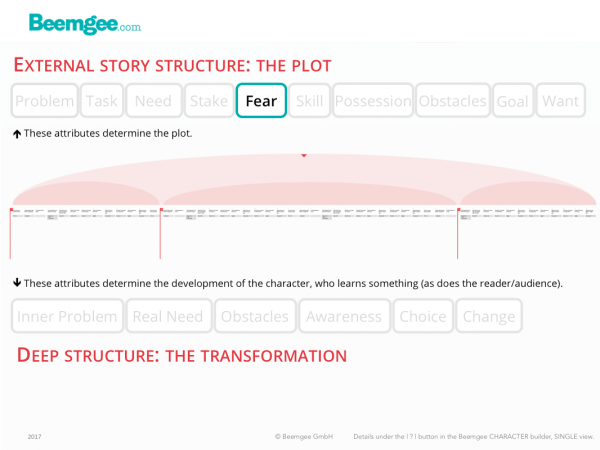

- Surface Structure and Deep Structure

- The Need for Awareness – or, Alternatives to Revelation

Becoming Aware – the importance of the revelation (more…)

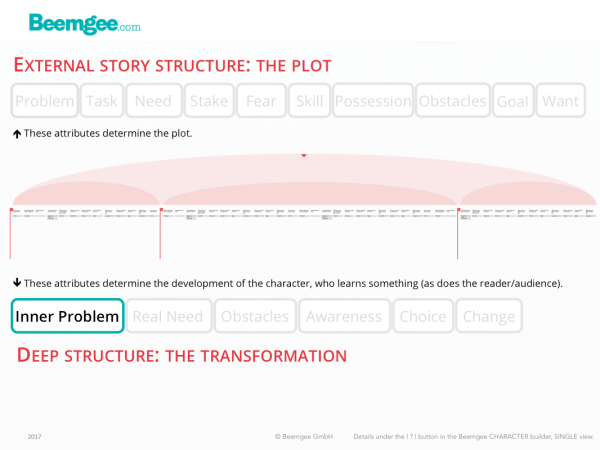

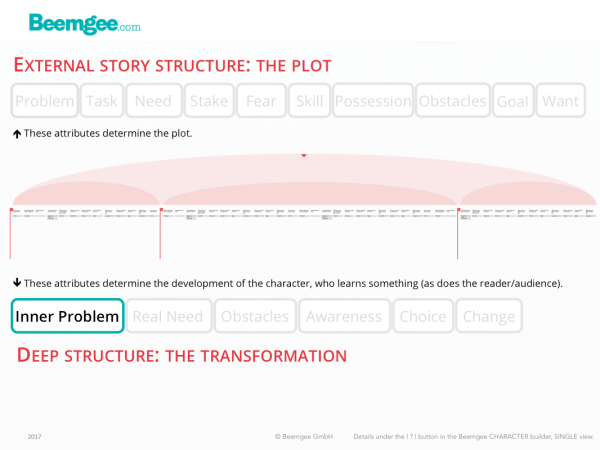

An inner or internal problem is the chance for change.

While the external problem shows the audience the character’s motivation to act (he or she wants to solve the problem), it is the internal problem that gives the character depth.

In storytelling, the internal problem is a character’s weakness, flaw, lack, shortcoming, failure, dysfunction, error, miscalculation, unresolved issue, or mistake. It is often manifested to the audience through a negative character trait. Classically, this flaw may be one of excess, such as too much pride. Almost always, the internal problem involves egoism. By overcoming it, the character will be wiser at the end of the story than at the beginning. Thus the character must learn cooperative behaviour in order to be a mature, socially functioning person.

The inner problem is the pre-condition for the character’s transformation. It is the flaw, weakness, mistake, error, or deficit that needs to be fixed. In other words, it shows what the character needs to learn.

Internal problems may be character traits that cause harm or hurt to others. They cause anti-social behaviour. And internal problems can also harm the character. They can be detrimental to his or her solving the external problem.

From Lack of Awareness to Revelation

While the external problem provides a character’s want, i.e. motivation, the internal problem provides the need.

The audience sees the flaw before the character does. The character is blinkered, has a blind spot. She first has to learn to see what the audience already knows. (more…)

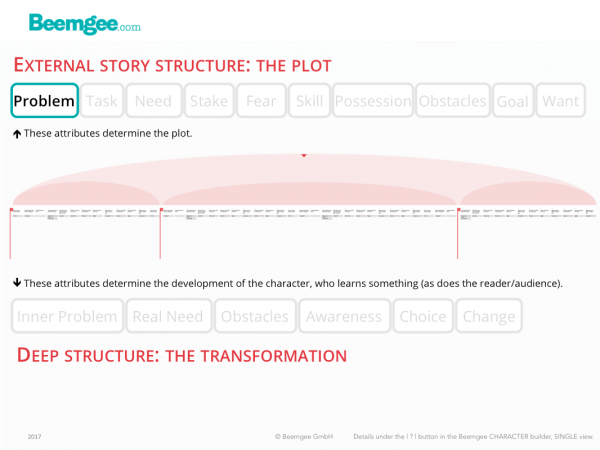

In stories, characters solve problems. This is the basic principle of story.

Problems come in all shapes and sizes. What’s more, in storytelling they come from within and without. The problems that come from within are hidden, internal, and it is quite possible for a character not to be aware of them. They are typically character flaws or shortcomings.

But they are not usually what gets the story going. Most stories begin with the protagonist being confronted with an external problem.

The external problem of the main character triggers the plot. It is shown to the audience as the incident which eventually incites the protagonist to action.

In some genres this is easy to see. In crime or mystery fiction, the external problem is almost by definition the crime or mystery that the protagonist has to deal with.(more…)

Stories need characters. What the characters do creates the plot.

With a well-rounded cast of characters, the plot will almost take care of itself. A story gets energy from the dynamic that occurs between the all the characters in it. The interaction between the characters is fueled by contrast, motivations, and conflict. Put a bunch of characters in a room – i.e. on a stage, between the covers of a book, between the first and last shots of a movie – and the plot is likely to emerge on its own. As long as there are contrasts between the characters and their motivations, conflict will arise.

So how does an author cast the characters that bring the story to life?

First of all, one character is rarely enough. Almost all stories need several characters. Even Robinson Crusoe couldn’t hold out alone. It’s the interplay between characters that creates interest. For interplay, read conflict.

Conflict in storytelling does not mean fights and battles. It means a conflict of interests.

Characters become characters because they have interests. Their interests make them do what they do, and this doing is what drives the plot.

What does that mean?

It means characters are motivated. They(more…)

Archetypes in stories express patterns.

While plots may be “archetypal” when they exhibit certain forms, in this post we are concerned with character archetypes.

In modern storytelling, to consider them as archetypes might suggest a bit of a corset, perhaps even a straightjacket for the characters. For today’s author, to present a character as an archetype does not seem conducive to achieving psychological verisimilitude.

But an archetype is not the same as a stereotype. An advisor or mentor does not need to be a wise old man like Obi-Wan Kenobi. And an antagonist does not need to be a baddy.

Consider archetypes as powers within a story. Like planets in a solar system, they have gravity and they therefore exert force as they move.

Archetypes denote certain general roles or functions for characters within the system of the story. There is ample room for variation within each role or function. Boundaries between one archetype and another may be fuzzy. And it is possible for one character to stand for more than one archetype.

Archetypes Through The Ages

(more…)

Stories are about people. Even the ones about robots, or rabbits, or whatever.

If you’re thinking about composing a story, you will probably have some characters in mind that will be performing the action of the story. In stories, action and actors (in the sense of someone who does something) are pretty much the same thing looked at from two differing perspectives, as we have noted in our post Plot vs. Character.

The most obvious difference between characters in stories and people in real life is that story characters tend to be driven. Narratives tend to be more compelling when the characters they describe are highly motivated. Rarely in life are our wants, goals, and perceived needs as clear and powerful as for characters in stories. Our real lives tend to drift rather than head in a specific direction; it is often in retrospect that we ascribe direction when we try to understand our lives by putting them into narratives. Historical personages who seem to demonstrate drive and direction (and have perhaps become historical personages because they had these qualities) make for more interesting biographies than people whose motivations were less strong.

Another aspect that sets characters in fiction apart from people in life is that characters tend to fulfil narrative functions in their story. People, on the other hand, live their lives by acting naturally according to the dictates of their personality. A story is a more or less enclosed unity, while an individual’s life is part of a greater whole. Only in retrospect do we sometimes overlay a narrative onto the biography of an individual – because we tend to feel happier when we perceive structure or direction in the lives of others or indeed our own. We can extract more meaning out of a life that can be told with structure and direction. In fact, there is no way of recounting a person’s biography without making choices concerning structure. If we’re honest, even the choice of which events to relate and how to relate them injects a fair amount of fiction into the story of a life, especially when that life is our own as we tell it to others or ourselves.

Many stories focus primarily on one protagonist. In fiction at least, the protagonist is often wiser at the end of the story than at the beginning. The(more…)

Here at Beemgee, we’re into the thought behind the writing of stories more than the writing itself. So we’re all the more pleased that

Here at Beemgee, we’re into the thought behind the writing of stories more than the writing itself. So we’re all the more pleased that