When the bad guy makes the hero’s journey difficult.

Let’s say your hero or heroine is a falsely accused fugitive from the law. While on the run, every policeman or government agent is effectively an antagonistic obstacle. This is particularly the case if there is a specific character who represents the state and whose mission it is to catch the heroine. This detective or agent casts out the net to catch the fugitive, using all the instruments of the state at his or her disposal in order to actively thwart the heroine’s escape.

Or maybe your story is about a soldier behind enemy lines on a mission to find and destroy (or steal) the enemy’s new super weapon, or perhaps rescue an important person who has been captured. Any enemy soldiers the hero encounters are, of course, obstacles. One could say that they are external obstacles if they just happen to be there, like a patrol unit. But if there is on the enemy side a character who is aware of our hero’s approach and is actively seeking to stop him achieving his mission, then the soldiers and/or henchmen this character sends out to find the hero are not external obstacles but antagonistic obstacles.

As we have said before, this division into three classes of obstacles – internal, external, and antagonistic – is not cut and dried and need not be followed too strictly. But differentiating between the different kinds of obstacles a hero or heroine must face while designing and planning your story can lead to a more exciting plot, simply because you can disperse the obstacles systematically within the story journey and have all the different kinds of obstacle build up to a great crescendo at the climax. (more…)

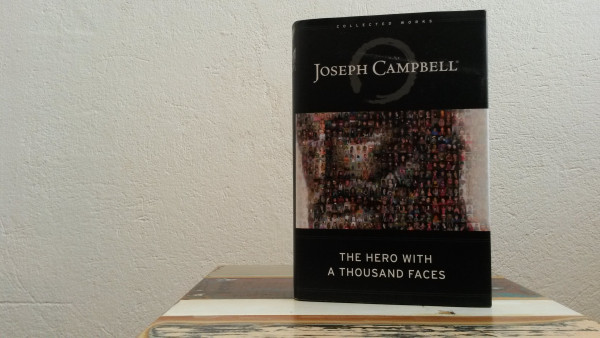

Joseph Campbell: The Hero With A Thousand Faces.

Joseph Campbell’s study of worldwide myths, The Hero With A Thousand Faces (1949), has become massively influential in commercial storytelling. Campbell was not the first to consider the concept of the hero and mythological or archetypal stories, and by no means the last (see Northrop Frye, as well as Robert Scholes and Robert Kellogg). But Campbell’s work consolidated what others, including Carl Jung, had suggested into a theory specifically about storytelling.

George Lucas read The Hero With A Thousand Faces as a young man, and we may assume that Francis Ford Coppola and Steven Spielberg were also familiar with the book. We can see the influence of Campbell’s ideas on some of the most successful movies of the 1970s and 80s, and ever since.

Christopher Vogler studied film at the same school as George Lucas, and subsequently while working at Disney wrote a seven-page breakdown of Campbell’s book. This in time developed into The Writer’s Journey, which has become the basis of the popular conception of The Hero’s Journey.

Campbell was an expert on James Joyce and a professor of literature with a particular interest in comparative mythology and comparative religion. The Hero With A Thousand Faces is by no means a how-to book or a storytelling manual. Rather, it posits the theory that all the myths of the world have elements in common and propounds the idea of the “monomyth” as a basic structural model of traditional storytelling. (more…)

Is there a recipe for successful stories?

In search of a recipe for success, Hollywood development executive Christopher Vogler wrote a seven-page practical guide for Disney to Joseph Campbell’s comparative analysis of worldwide myths.

George Lucas had already stated his debt to Campbell in the development of Star Wars, and the idea that there might be a template for stories that are so successful they last over centuries and across cultures caught on quickly in Tinseltown. (more…)

In essence, there are three kinds of opposition a character in a work of fiction may have to deal with:

- Character vs. character

- Character vs. nature

- Character vs. society

However, this way of categorising types of opposition is not equivalent to internal, external and antagonistic obstacles. Any of the three kinds of opposition listed above may be internal, external, or antagonistic. It depends on the story structure.

External opposition

In any story, the cast of characters will likely be diverse in such a way as to highlight the differences and conflicts of interests between the individuals. In some cases, certain roles may be expected or necessary parts of the surroundings, i.e. of the story world. In the story of a prisoner, it is implicit that there will be jailors or wardens, whose interest it will be to keep the prisoner in prison, which is in opposition or conflict with the prisoner’s desire for freedom.(more…)

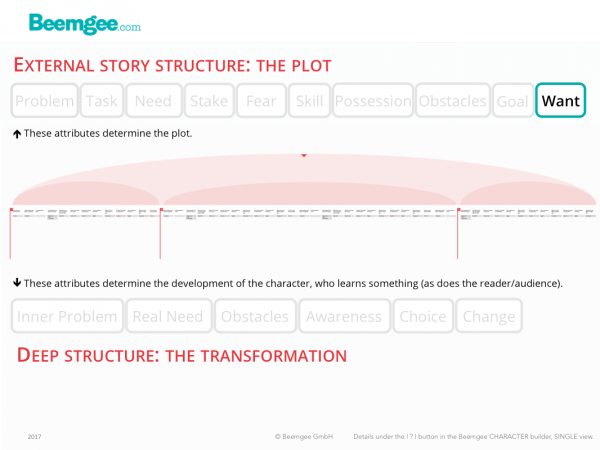

Stories are about people who want something.

We can distinguish between two different types of want:

- the wish, or character want

- the plot want

Marty McFly wishes to be a musician (character want). He also wants to get Back to the Future (plot want).

The wish or character want is a device which adds cohesion to the story, usually in the form of the set-up/pay-off. Marty is seen at the beginning of the film practicing the guitar; at the end of the film he plays at a concert. A character-inherent wish is a useful technique to make the character clearer to the audience, but it is not essential to composing a story.

Indispensable is what we have called the plot want. As a result of the external problem – the trigger event that sparks the chain of cause and effect which the bulk of the plot consists of –, the character feels an urge, which provides the motivation for the character’s actions in the story.

The want is the state for which the character strives, and is distinct from the goal.

In this post we’ll be talking about active vs. passive characters, motivation, the difference between a want and a goal, a couple of writer traps to avoid, and contradictory wants.

Active Characters

Characters have to be actively acting of their own volition. The want has to be urgent and strong enough for them to do things. If the want is missing or too weak, the character will lack motivation and appear passive. A passive character is usually not interesting enough to hold the audience’ or readers’ attention.

Why is this so?

Evolutionary explanations of stories attempt to shed light on the phenomenon. When characters react to events rather than cause them, they appear weak, as victims in a chaotic, uncontrolled world. Which means that there is not much we can learn from them. Humans try to see cause and effect in everything, not just in stories. And humans experience stories physically and emotionally (our hearts beat faster, our palms sweat), so there is really not much difference between how we experience a story and real life. Since we learn from experience, we instinctively prefer stories which provide us with experiences that benefit us in some way. In stories we vicariously experience or practice primarily social problem-solving, without suffering real-life consequences. We tend to learn more when we experience stories of self-motivated problem-solving.

Motivation

There is a good reason for that cliché about actors always asking about their motivation. It is motivation that prompts the characters in a story to do the things they do. Stories seem to work best not only when characters are active rather than passive, but often when they have comprehensible reasons for their activity.

The reason for what a character wants is usually comprehensible for the audience or reader because of the external problem. In simple terms, the character wants to solve the problem. Take the Cinderella story as an example. Her problem is that she is bound to the stepmother and her two nasty daughters.

In other words, the want is a vision the character has of his or her situation without the problem. Hence what the character wants is actually a particular state of being. Such a state might mean being in a position of wealth, power or respect, or being in a happily ever after relationship. Cinderella wants merely to be free of her involuntary servitude, if only for a little while.

This makes the want distinct from the goal, which is the specific gateway to the wanted state of being, as perceived by the character. A story usually sets up a goal the character needs to reach or attain in order to achieve the want. In Cinderella’s case, it is attending the ball.

So, a story has its characters pursue their wants. These different wants oppose each other, causing conflicts of interest. The conflicting wants make the characters active, and the audience/readers like stories about actions, that is, about characters who do things.

Sounds simple.

And yet frequently stories seem to mess up on this vital point.

Next to passive characters without a strong enough want, lack of clear motivation is a huge writer trap. It is possible to write a whole story full of characters who are reactive instead of active, or who do things of their own volition but without that volition being clearly recognisable to the audience/reader. It is perhaps even tempting to write stories like that, because they seem more lifelike. In real life, people do not necessarily have distinct goals. Often, our wants are vague and not clearly definable. What about writing a realistic story about a character with a general sense of dissatisfaction, who, like so many of us, has lost sight of any clear objective in life?

It’s doable, certainly. But the audience/readers will probably start to look for the specific want of such a character. They would probably begin to expect the story to be about this character’s search for a clear objective in life. That might be the want the audience would tacitly ascribe to the character.

And if the story does not bear such motivation out, the risk is significant. Because stories in which the audience does not understand what the characters want lack emotional impact.

Contradictory Wants

A way of adding psychological depth and emotional complexity to characters is to give them several and even contradictory wants. Gollum in Lord Of The Rings wants the ring. Yet a part of him also wants to give up the ring and help Frodo. Next to solving the case, Marty Hart in True Detective wants to be a good husband and family man, but he also wants affairs with other women. That’s three wants for one character.

A want is not merely a yearning, it is an expression of values. What a character desires shows the audience something about that character. In this sense, two contradictory wants provide the basis for a powerful scene of choice. At a crisis point, the character may face a dilemma and have to choose between two courses. Both might lead to some state the character desires, but these desires prove to be mutually exclusive. For the audience, which choice is the right one might be obvious – they will be rooting for the character to go one way. But for the character there may be a strong pull the other way. The final choice shows the character’s moral fibre – and often expresses the story’s theme.

When not to want

Is it really always absolutely necessary for every character to have a clearly defined want?

Not entirely. Because, of course, there are exceptions.

In certain cases, the author might deliberately obfuscate the why of a character’s actions in order to inject mystery. Not knowing something keeps the audience/reader guessing and turning the pages or not switching the channel. Usually this mystery is cleared up at some point. The audience tends to expect that. Which implies that even if the want was not made clear to the audience early in the story, it was there in the character nonetheless – and certainly the author was aware of it.

Injecting mystery by keeping character motivations hidden is not in itself a writer trap. But nearly. When tempted to use such a device, an author should at least consider if it would not actually be more interesting for the audience to know the character’s motivation.

Having said that, there are rare cases where a character’s motivation does remain unexplained. And those cases can be powerful. Especially when it’s a baddy we don’t understand.

Think of Iago in Shakespeare’s Othello, who is simply bad to the bone and we’ll never really know why. Shakespeare – deliberately, one presumes – gives no hint as to what Iago hopes to achieve by ruining Othello. Shakespeare might easily have given Iago some clearly understandable motivation, such as revenge of a past wrong, envy of Othello’s success, desire to usurp Othello’s position, lust for Desdemona. But he didn’t. And Iago is one of the most superb villains ever.

Another possible exception are (fiction) memoirs in the first person, such as David Copperfield, The Catcher in the Rye, Saul Bellow’s The Adventures of Augie March, or William Boyd’s Any Human Heart. In such stories, the effect of the narrator telling his or her own story creates a disparity between the time of the story told and the implicit future time of the act of telling. The narrator is relating a past from the perspective of an older self. This older self has reached a state of being which is different from that of the character being told about – the narrator is wiser than his or her younger self. This creates an effect for the reader: the reader wants to know how the character reach this older, wiser state. With this device, it is possible to make character wants less obvious or direct and still maintain an emotional drive to the story.

Perhaps the most interesting thing about a character’s want is how it stands in conflict with what that character really needs.

Related function in the Beemgee story development tool:

Character Developer

Click to open a new story project:

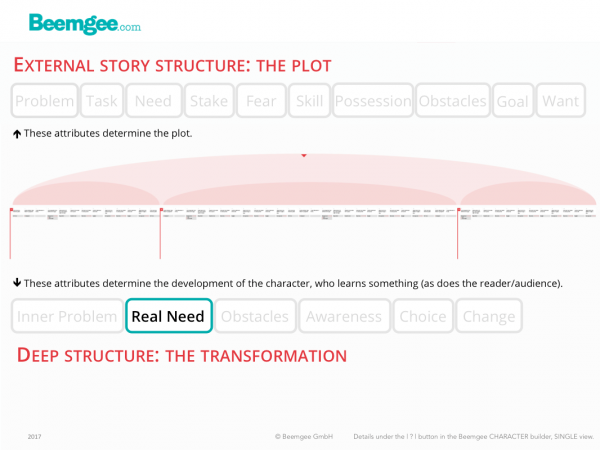

In most stories, what a character really needs is growth.

Characters display flaws or shortcomings near the beginning of the story as well as wants. What they really need to do in order to achieve what they want is likely to be something they need to become aware of first.

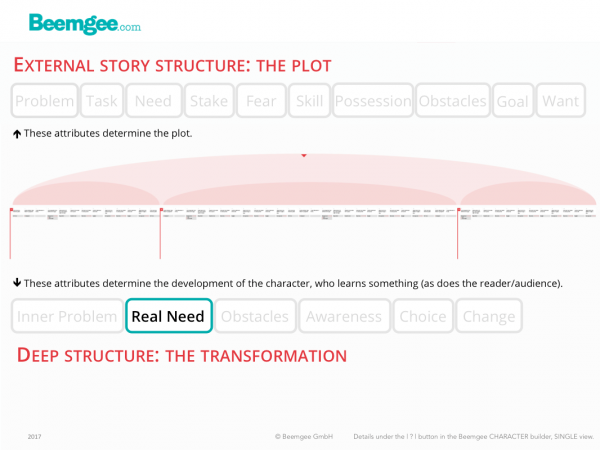

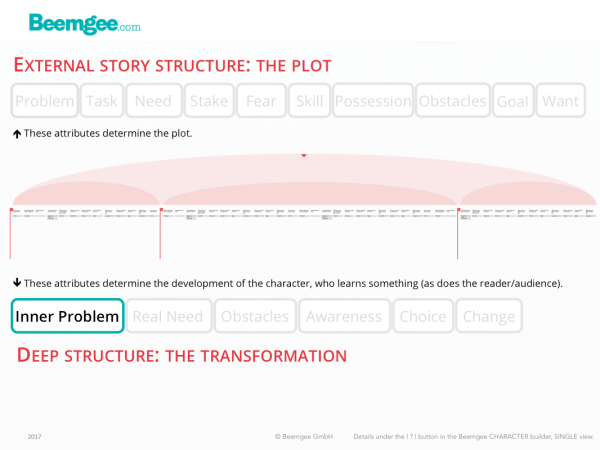

The real need relates to the internal problem in the same way the perceived need relates to the external problem. The character has some sort of dysfunction that really needs to be repaired.

That means the audience or reader may become aware of a character’s real need long before the character does. Most stories are about learning, and learning entails the uncovering of something previously unknown. So the real need of a character is to uncover the internal problem, to become aware of their flaw.

A character may be unaware of their real need because they are suppressing a secret from their past. Something they did (better than something that happened to them) causes shame or guilt and they therefore hide it from themselves. To get over this, they must achieve some sort of healing. The trick is to dramatise such inner conflict through plot events.

To recap: The usual mode in storytelling has a character consciously responding to an external problem with a want, a goal, and a number of perceived needs. Unconsciously, that character may well have a character trait that amounts to an internal problem, out of which arises that character’s real need – i.e. to solve the internal problem.

So if a character is selfish, the real need is to learn selflessness. If the character is overly proud, then he or she needs to gain some humility. In the movie Chef, the father neglects his son emotionally – his real need is to learn to involve the child in his own life. The audience sees this way before the Chef does.

Even stories in which the external problem provides the entertainment – and with that the raison d’être of the story – may profit from(more…)

What’s the problem? Does the character know?

In storytelling, discrepancy between a character’s awareness and the awareness-levels of others is one of the most powerful devices an author can use. “Others” refers here not just to other characters, but to the narrator and – most significantly – to the audience/reader.

Let’s sum up potential differences in knowledge or awareness:

- A character’s awareness of his or her own internal problem or motivation

- A difference between one character’s knowledge of what’s going on and another’s

- The narrator knows more about what is going on than the character

- The audience/reader knows more than the character – dramatic irony

In this post, we’ll concentrate on the first point: Awareness of the internal problem. We’ll break that down into

- Becoming Aware – the importance of the revelation

- The Story Journey – and where to place the revelation

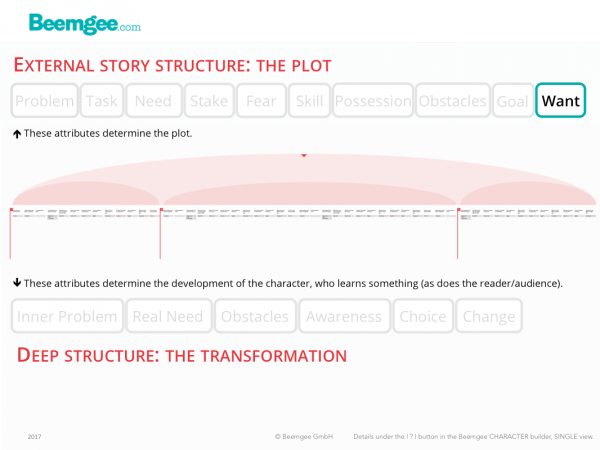

- Surface Structure and Deep Structure

- The Need for Awareness – or, Alternatives to Revelation

Becoming Aware – the importance of the revelation (more…)

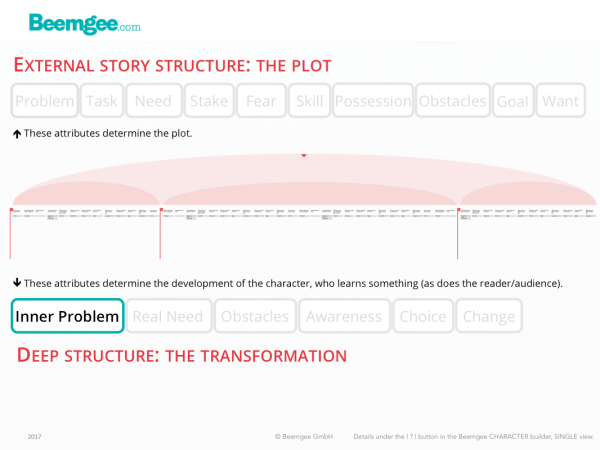

An inner or internal problem is the chance for change.

While the external problem shows the audience the character’s motivation to act (he or she wants to solve the problem), it is the internal problem that gives the character depth.

In storytelling, the internal problem is a character’s weakness, flaw, lack, shortcoming, failure, dysfunction, error, miscalculation, unresolved issue, or mistake. It is often manifested to the audience through a negative character trait. Classically, this flaw may be one of excess, such as too much pride. Almost always, the internal problem involves egoism. By overcoming it, the character will be wiser at the end of the story than at the beginning. Thus the character must learn cooperative behaviour in order to be a mature, socially functioning person.

The inner problem is the pre-condition for the character’s transformation. It is the flaw, weakness, mistake, error, or deficit that needs to be fixed. In other words, it shows what the character needs to learn.

Internal problems may be character traits that cause harm or hurt to others. They cause anti-social behaviour. And internal problems can also harm the character. They can be detrimental to his or her solving the external problem.

From Lack of Awareness to Revelation

While the external problem provides a character’s want, i.e. motivation, the internal problem provides the need.

The audience sees the flaw before the character does. The character is blinkered, has a blind spot. She first has to learn to see what the audience already knows. (more…)

Theme is a binding agent. It makes everything in a story stick together.

To state its theme is one way of describing what a story is about. To start finding a story’s theme, see if there is a more or less generic concept that fits, like “reform”, “racism”, “good vs. evil”. The theme of Shakespeare’s Othello is jealousy.

Once this broadest sense of theme is established, you could get a little more specific.

The theme is the expression of the reason why THIS story MUST be told! The theme of a story holds it together and expresses its values.

Theme may therefore be seen as an implicit message. But make sure that the message remains implicit, allowing the audience to understand it through their own interpretation.

Since a theme is usually (though not always) consciously posited by the author, it has some elements of a unique and personal vision of what is the best way to live. At best, this is expressed through the structure of the story, for instance by having the narrative culminate in a choice the protagonist has to make. The choices represent versions of what might be considered ways to live, or what is “right”.

But beware! This is a potential writer trap. See below.

How story expresses theme

Theme is expressed, essentially, through the audience’s reaction to how the characters grow. A consciously chosen theme seeks to convey a proposition that has the potential to be universally valid. Usually – and this is interesting in its evolutionary ramifications – the theme conveys a sense of the way a group or society can live together successfully.(more…)