The Two Types of Non-Fiction Book.

Here at Beemgee, we know a lot about how stories work. We consider ourselves experts on dramaturgy and narrative. Fiction is our forte.

But we don’t claim to understand non-fiction anywhere near as well. That’s why we were very keen to attend a session on non-fiction by Yvonne Kraus at the author conference at this year’s Leipzig book fair.

Here’s a brief summary of what she taught us.

The Two Basic Structures of Non-Fiction Books

1. Reference and articles

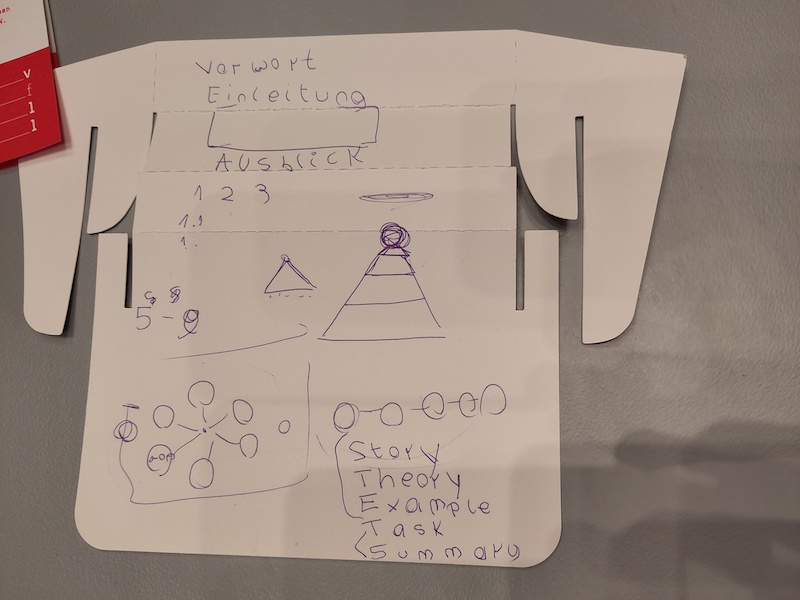

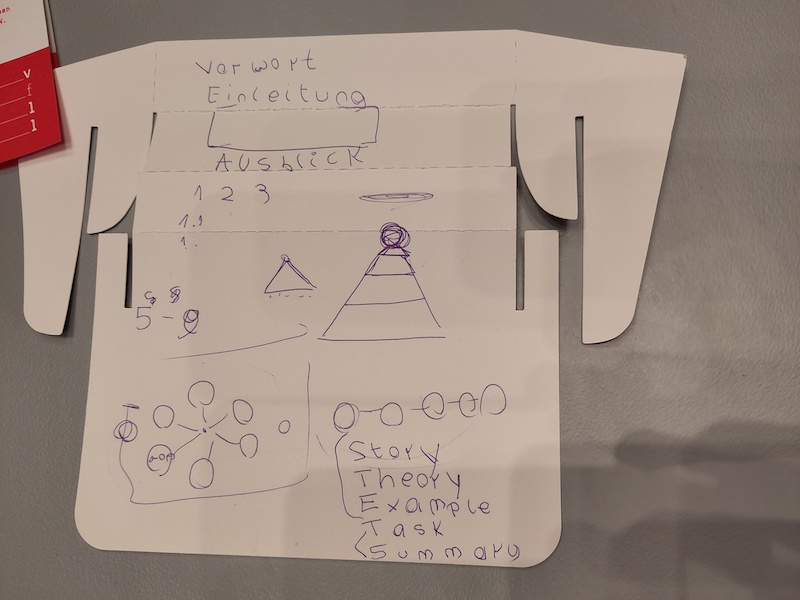

Look at the bottom left of the scribble in the photo and you’ll see circles arranged in a circle, with lines going from the individual circles into the center of the arrangement. Each individual circle stands for a unit of content, or a chapter. This representation is trying to express a way of reading a book. The reader can dip into any chapter at will, they each function independently of each other, it is not necessary to read them in sequence or to read all of them. Cookbooks are a good example. Each recipe constitutes a chapter, a unit, and can be consulted without knowing the other units.

If we are talking about content more complex than recipes, for example political articles, the units may contain information that is repetitious in the book as a whole if this information is necessary in order to understand the content of several individual chapters. I.e. it may well be the case that the same basic facts are stated in several of the chapters if they are requisite to know, because the author cannot assume that the reader will have read previous chapters in the book already. The chapters do not build on each other. Certain units of information may be referenced, for example a lasagne recipe may call for béchamel sauce, the making of which may not be described in the lasagne recipe but instead the lasagne recipe may simply say, “see the recipe for béchamel sauce on page 27 in the section ‘basic sauces'”.

The main body of the book may be subdivided into meaningful sections. The promise the book makes to the reader is that the reader will find specific information on a particular subtopic easily, and without having to read the entire book. (more…)

These are remnants of our sessions at the wonderful Author Conference at the Leipzig Book Fair, LBM24. As you can see, we really can’t draw. Nonetheless we tried to illustrate sophisticated approaches to storytelling such as:

– figural shadowing

– liminal storytelling

– cyclical and rhythmic storytelling

We hope our participants gained some valuable insights!

Click to develop a better story:

Guest post by Ali Luke.

Ali Luke is a freelance writer and novelist who blogs about making the most of your writing time at Aliventures. For her best tips on making time to write, sign up for her email newsletter: you’ll receive a free copy of her mini ebook Time to Write: How to Fit More Writing Into Your Busy Life, Right Now.

Ali Luke is a freelance writer and novelist who blogs about making the most of your writing time at Aliventures. For her best tips on making time to write, sign up for her email newsletter: you’ll receive a free copy of her mini ebook Time to Write: How to Fit More Writing Into Your Busy Life, Right Now.

Pacing in fiction is how quickly—or slowly—the story progresses. The right pace for a story depends on its genre. If you’re reading a thriller, you’ll expect a fast-paced read with lots of action; if you’re reading a historical novel or epic fantasy, you might enjoy a slower pace with lots of emphasis on the world of the story.

It’s tough to get pacing spot-on when you’re drafting. It might take you years to write a book that takes just hours for someone to read. What feels “slow” to you as you write might actually go by pretty quickly on the page. Or, you may find that you repeat yourself, going over the same narrative ground multiple times, because you barely remembered what you wrote six months ago.

So, don’t worry about your pacing as you draft. Instead, address it in the redrafts—ideally, with the help of beta readers, but even simply reading over your full manuscript yourself can help you spot areas where the pace feels off.

Here’s what to look for when redrafting your work. (more…)

So wrote the great film director Sidney Lumet.

As we have seen, there are two parts of the process to creating a story. One is concerned with the story itself, with what the story comprises and the arrangement of its elements. The other has to do with how you tell it, with the text of the manuscript or screenplay.

Or let’s try another approach to understanding how interwoven the two aspects structure and words are. In Chinese, the word for literature and writing is “wen”, and this word originally meant “pattern”, or design, as for example of woven silk. A pattern is structure.

Consider a tree in winter. Its trunk and branches are the ‘bare bones’ of the organism. Only in spring and summer, when leaves and flowers come out, does it really come alive, does it truly reach its full potential in our eyes, does it become a complete tree in its ideal state. Without the trunk and branches there would be nowhere for the leaves and flowers to grow. So perhaps as an analogy we can see the trunk and branches as the story, and the leaves are the words. And the flowers? Well, maybe they are metaphors …

As Lu Chi put it in third century C.E.,

“When the substance of a composition, trunk of a tree, is by Truth sustained,

Style aids it to branch into leafy boughs and bear fruit.”

Translation Shih-Hsiang Chen, in Cyril Birch’s Anthology of Chinese Literature (more…)

Long or short form, commercial or artistic: stories need to be developed before they are told.

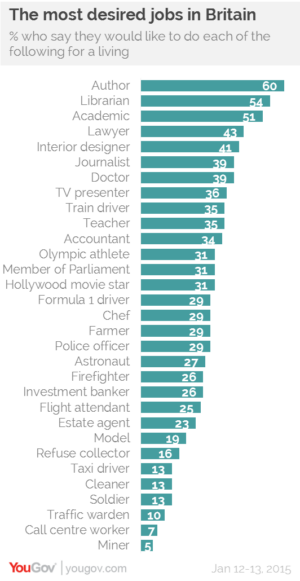

The fewest of people with the inclination to write stories actually make a living off it. There are more unsuccessful authors and screenwriters than successful ones, if we measure success in terms of monetary remuneration. And there are yet more people who would love to write that book but never seem to get around to it.

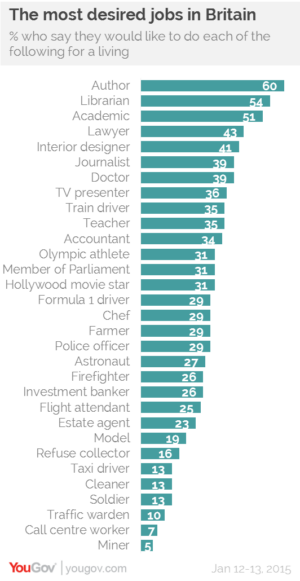

In fact, according to a 2015 YouGov poll in the UK, being an author is the most desirable job in that country. 60% of Britons want to write for a living! In the land of the Bard, J.K. Rowling, and Richard & Judy, perhaps that is not so surprising. Yet we may assume that in other countries too, the desire to tell stories is quite prevalent.

Practice makes perfect, so they say. The best way for a writer to improve their writing is to write. You may have heard of the theory that to be really, really good at something, you need to have done 10,000 hours of it.

But who has 10,000 hours to spare before producing anything readable?

We would contend that any writing is practice. The artist in the garret must eat and so a suitable option would be earning from writing. This is, after all, an age in which content is regent. Perhaps it is even true that more stories are being told today than ever before. There is an abundance of media and channels, and all must be filled with material. Hundreds of original series are being produced for the streaming services, cinema is not dead after all, and neither is TV, publishers are still publishing novels while self-publishers do it too.

Advertising is another field in which storytellers can hone their craft. Every company needs its image video, every product its presentation. Even towns, nonprofits, and unions tell stories. (more…)

A story has a beginning, a middle, and an end. How to avoid the ‘saggy middle’.

The middle bit of a story is really the story proper. It is usually the longest section. It comes after the introduction of the main character(s) and the setting up of the context, that is the world of the story, as well as the problems and themes the story deals with.

At the end of the first section – prior to what we’re here calling ‘the middle bit’ –, the protagonist has decided to set off on the story journey. Obviously, this does not have to be physical journey through a particular geography, but it does mean that the main character is somehow entering into new and unfamiliar terrain. In this sense, every story is a ‘fish out of water’ story. The heroine must leave the comfort zone in order for the audience to feel interest in her plight.

Some authors jump right into this unfamiliar territory, showing the run up to it in flashbacks. Anita Brookner’s heroine Edith Hope has already arrived in the Hotel du Lac in the first sentence of the novel. Gradually the reasons for her stay here are revealed as the reader progresses through the novel.

Nonetheless, for an author, it may be advisable to create a marked threshold where the protagonist enters into the alien territory of the middle bit. The exploration and transversal of this territory is what on a plot level the middle bit is about, and it takes up the greater part of the story journey. (more…)

Creation Takes Time.

This is an age of faster, faster, more, more. At the latest since the advent of the internet, everything seems to be speeding up. Processes that took weeks a few decades ago now take only a few hours, things that in the twentieth century took hours now take place within minutes or seconds. You can get from A to B in less time than ever. The requirements on most of us for most of our work call for ever greater efficiency. We must not waste time. We must be quick.

Composing a story is a painstaking process. And yes, here at Beemgee we built our fiction tool in order to make the process of composing a story more efficient. We want to make it easier to organise a plot and determine the characters’ motivations – for the authors themselves, and for all the people communicating about the story, so between interested parties such as authors and their editors or screenwriters and producers.

But though we might want our authors’ efficiency to increase, let’s not kid ourselves. Composing a story is still a painstaking process. Because most of the time is spent thinking.

Thinking takes time. And that is mostly what plotting and outlining a story really is, thinking. (more…)

The midpoint is structurally the most significant point in a narrative.

Given that stories have a tendency to symmetry, the centre of a narrative should mark the zenith of the story arc, and with that, the pivotal point of the story.

So, to get to (mid)point: What happens in the middle of a story?

Here are some typical midpoint events:

- Something searched for is found (Star Wars IV, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Lolita)

- A hidden truth is unveiled (to the audience, at least) – if not yet understood (Matrix, Pride and Prejudice, The Gruffalo)

- A dramatic event thwarts all plans made hitherto (James Cameron’s Titanic)

The centre of the narrative may be the discovery of something missing – in crime stories a vital piece of the puzzle may be revealed here (either to the audience or to the audience as well as the protagonist).

In any genre or dramatic category, the midpoint may be a moment of truth. This might be just a clue for the audience or perhaps an initial revelation of the true state of things.

If a character realises or finds out something that has so far been hidden, then this is the point at which the character begins to gain awareness. This counts in particular for the recognition of the character’s own internal problem. From here on the story might possibly lead up to a moment of choice at the crisis, when it becomes clear to the audience whether the character has learnt from this new awareness or not. In other words, the real need begins to overcome or supplant the character’s initial want due to what happens at the midpoint.

Some well-known examples of the midpoint

(more…)

Today’s guest post is by author Stefan Emunds.

Today’s guest post is by author Stefan Emunds.

Stefan’s favorite genre is visionary fiction – stories that have an enlightenment dimension. Enlightenment and storytelling have interesting parallels, which prompted Stefan to write a book about storytelling – The Eight Crafts of Writing.

Get a glimpse of his approach to story craft in his article.

Art and Craft

Storytelling is both art and craft, authoring and writing, plotting and pantsing.

1.1 Art and Authoring

Art is creativity. Creativity requires receptivity to the Muse and its inspirations.

Inspirations arrive as thought-images, which writers put into words. How to turn thought-images into words and assemble those into a structured story with vivid characters and an engrossing world is a matter of craft and skill.

1.2 Craft and Writing

The literal meaning of Kung Fu is a discipline achieved through hard work and persistent practice. Writing is Kung Fu.

Craft gives form to inspirations. Forms limit. Writers love the artistic side of writing, less so crafting, in particular, Story Outline. Writers are prone to procrastinate crafting.

But no limitations, no story. No canvas, no painting. No net, no tennis.

Understanding the difference between freedom and dominion helps to appreciate the constraints of craft. Freedom is a means to an end. We want to be free to do something, for example, to write a book. That’s all there is to freedom. Dominion, on the other hand, is mastery of structure. (more…)

Nothing should be more important to an author than how their story makes the audience feel.

As an author, consider carefully the emotional journey of the reader or viewer as they progress through your narrative.

The audience experiences a sequence of emotions when engaged in a narrative. So narrative structure is a vital aspect of storytelling. The story should be touching the audience emotionally during every scene. Furthermore, each new scene should evoke a new feeling in order to remain fresh and surprising.

The author’s job is to make the audience feel empathy with the characters quickly, so that an emotional response to the characters’ situation is possible. Only this can lead to physical reactions like accelerated heartbeat when the story gets exciting. We have to care.

This “capturing” of the audience, making the reader or viewer rapt and enthralled, requires authors to create events that will show who the characters are and how they react to the problems they must face. The audience is more likely to feel with the characters as the plot unfolds when the characters’ reactions to events reveal something about who they really are – and how they might be similar to us.

One Journey to Spellbind Them All

Here we present a loose pattern that we think probably fits for any type of story, whatever genre or medium, however “literary” or “commercial”. It’s not prescriptive, just a rough checklist of the stages in the emotional journey the audience tacitly expects when they let themselves in on a story. The emotions are in more or less the order they might be evoked by any narrative.

Curiosity

(more…)

Guest Post by KT Mehra.

KT Mehra knows a thing or two about writing from her own experience, not only as an author but as a supplier to writers and authors of fine stationary, in particular fountain pens. Not only that, she is digital savvy too.

Back in 1999, KT and her husband Sal started a small web company to create websites for local businesses and provide internet access. They both had a passion for fountain pens, and one day KT, in an excess of enthusiasm, ordered far too many from a pen company. Just for fun, she decided not to return any of them and instead asked her team to design an e-commerce website to sell the extra pens.

To everyone’s surprise and just like that, the website came together quickly and was an instant success.

KT believes that in the modern digitally saturated world, it’s more important than ever to stay true to your thoughts and create something tangible. In that spirit of creation, she feels that something as elemental as putting pen to paper is ever more essential.

Despite offering a digital tool for authors, we couldn’t agree more!

Develop a romantic relationship that your readers will engage with and root for.

Most of the romance novels you love so much use certain secrets to hook their readers in and keep them engaged.

Learning the secrets to create such compelling romance novels will help you perfect your characters’ love story.

The Basics

The best way for your readers to relate and root for your relationship is for you to make it realistic and dynamic. To build the foundation of any great love story, you need to have a few things down first. (more…)

Outlining a story means developing the characters and structuring the plot.

Beemgee will help you outline your plot using the principle of noting ideas for scenes or plot events on index cards and arranging them in a timeline. This is a separate process from actually writing the story. Most accomplished authors outline their stories before writing them, because it saves rewrites later.

Find a video here.

In this post we will explain –

The Beemge author tool is divided into three separate areas, PLOT, CHARACTER and STEP OUTLINE. You navigate them easily in the top menu.

Important note: Make sure to stay in the same browser window in whichever area you’re working. Having one project open in multiple windows may result in some of your input being lost.

How To Create An Event Card

(more…)

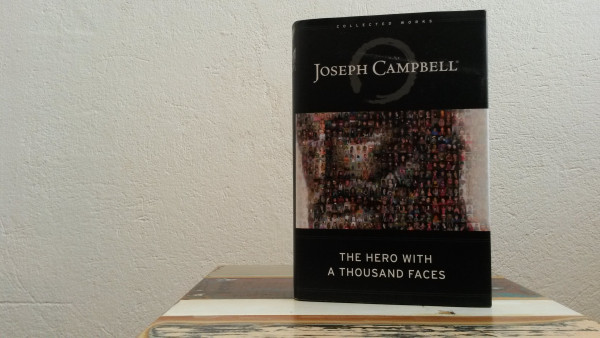

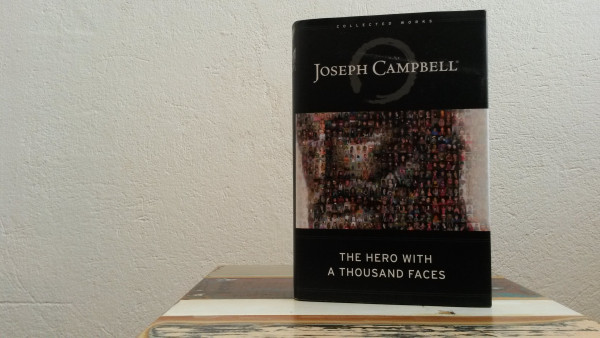

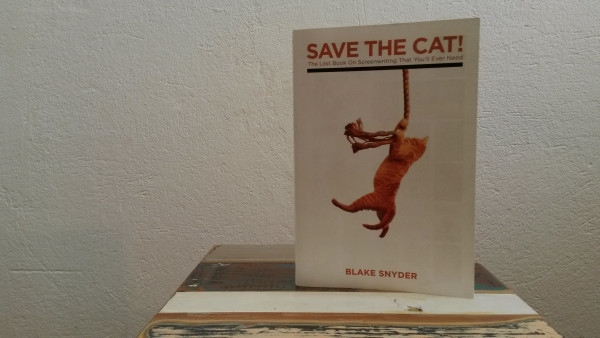

Joseph Campbell: The Hero With A Thousand Faces.

Joseph Campbell’s study of worldwide myths, The Hero With A Thousand Faces (1949), has become massively influential in commercial storytelling. Campbell was not the first to consider the concept of the hero and mythological or archetypal stories, and by no means the last (see Northrop Frye, as well as Robert Scholes and Robert Kellogg). But Campbell’s work consolidated what others, including Carl Jung, had suggested into a theory specifically about storytelling.

George Lucas read The Hero With A Thousand Faces as a young man, and we may assume that Francis Ford Coppola and Steven Spielberg were also familiar with the book. We can see the influence of Campbell’s ideas on some of the most successful movies of the 1970s and 80s, and ever since.

Christopher Vogler studied film at the same school as George Lucas, and subsequently while working at Disney wrote a seven-page breakdown of Campbell’s book. This in time developed into The Writer’s Journey, which has become the basis of the popular conception of The Hero’s Journey.

Campbell was an expert on James Joyce and a professor of literature with a particular interest in comparative mythology and comparative religion. The Hero With A Thousand Faces is by no means a how-to book or a storytelling manual. Rather, it posits the theory that all the myths of the world have elements in common and propounds the idea of the “monomyth” as a basic structural model of traditional storytelling. (more…)

There are two definitions of story beat. Both of them refer to a change.

One use of the term beat refers to the subtle change in the dynamic of a relationship that a line of dialogue brings about in a scene. There are usually several beats within a scene, each a marker for pushing the scene forwards dramatically.

The other meaning of the word beat in storytelling applies to changes in the plot brought about by scenes. A plot is a succession of events linked causally, a narrative chain of cause and effect. One event effects a change, determining what happens in subsequent scenes. Writers might arrange these events on a board or “beat sheet” during the planning phase. (more…)

If a story is your original idea, then the copyright to it is by default yours.

However, copyright is a complex legal issue we cannot hope and don’t even want to explain properly here.

Each country has its own copyright laws. Also, copyright usually doesn’t apply until there is a pretty concrete manifestation of a “work”. It is easier to establish the copyright of the text of a novel than of the story the novel recounts. A story idea or even a fairly detailed outline may not qualify for legal copyright. But if you have a project in the form of a detailed outline which has a date to it, you have at least a way of asserting your moral rights to the intellectual property. (more…)

What is the difference between commissioning editors, developmental editors, and line editors?

Photo by Patrick Tomasso on Unsplash

Let’s look at what each do to see the differences between the three different kinds of editors. And then find the other editorial task they all have in common.

The Commissioning Editor

An example (more…)

How narrative structure turns a story into an emotional experience.

Image: Comfreak, Pixabay

Storytelling is a bit of an overused buzzword. While we are all – by dint of being human – storytellers, how aware are you of the principles of dramaturgy? What exactly constitutes a story, in comparison to, say, a report or an anecdote?

And just to be clear, the following is not a story. It’s an how-to article.

Whatever the medium – film or text, online or offline –, storytelling has something to do with emotionally engaging an audience, that much seems clear. So is a picture of a cute puppy a story? Hardly.

Stories exist in order to create a difference in their audience. Stories always address problems and tend to convey the benefits of co-operative behaviour.

While there simply is no blueprint to how stories work, let’s examine the elements that recur in stories and try to find some patterns.

Who is the story about?

All stories are about someone. That someone does not have to be a person, it can be an animal (Bambi) or a robot (Wall-e). But a story needs a character. In fact, all stories have more than one character, with virtually no exceptions. This is because the interaction between several characters provides motivation, conflict and action.

Moreover, stories usually have a main character, the figure that the story seems to be principally about – the protagonist. It is not always obvious why one character is the protagonist rather than another. Is she simply the most heroic? Is she the one that develops most? Or does she just have the most scenes?(more…)

Antje Tresp-Welte is the winner of the Your Perfect Plot challenge set by BoD and Beemgee.

In her guest blog post, she gives frank insight into her writing process and her experiences with Beemgee.

Short stories were child’s play

Short stories were child’s play

When something intrigues me, I spin a story out of it. Until a few years ago I wrote mostly fairy tales, short stories for adults, poetry and stories for younger children, some of which were published in magazines. My story about a bad-tempered spectacled snake was published as a little book, “Charlotte and the Blue Lurker”. For all these stories I only sketched a few thoughts as planning and then wrote them down relatively quickly.

By now, book projects fascinate me too. Currently they are crime novels and fantasy for children from 8 or 10 years.

Long takes longer …

During a holiday at the North Sea I had the idea for my first crime novel. In it, the protagonist, an eleven-year-old very imaginative boy with a penchant for drawing, not only saves his grandma’s tea room from demolition, but is also involved in a mysterious story about a pirate who died long ago. I developed the original idea into a plot at a seminar for authors. I found the topic so great that I couldn’t wait to start writing it. Beforehand, I made notes on the individual characters and considered important cornerstones of the plot with the help of the hero’s journey. I started off with a great momentum and was soon able to read the first chapters to my son. Unfortunately his comment was, “Mama, that is much too long!”

… not to be longwinded

My two test readers came to a similar conclusion and I too had noticed that it somehow “grated”. I wasn’t really getting to the point. Was it due to my preliminary planning? Was it not detailed enough? I dived into the text, shortened passages, removed individual characters and worked out others more precisely. This changed entire storylines. At the same time my story gained more (narrative) speed and I found the tone for the language. (more…)

The process of writing is unique to each author.

There is no right or wrong way to write a work of fiction. Perhaps the main thing is to just sit down and get on with it.

Many authors start by writing the beginning of the story and working their way through to the end. This seems intuitive, as it mirrors the way narratives are normally received – from opening to resolution. Furthermore, it allows a development of the material that feels natural, beginning probably with a setting and a character or two and growing in complexity as the story progresses.

But this isn’t the only way to get a story written. The author is not the recipient, after all. The author is the creator.

Creative habits seem to differ according to medium. Most screenwriters spend a lot of time working out the intricacies of plot and complexities of character before beginning to actually write the screenplay. Some novelists, on the other hand, seem to require the writing process in order to get to grips with the material. For such authors, the act of working on text is so intimately intertwined with the craft of dramaturgy that the shaping of the story has to be performed simultaneously with the writing of it.

Flow

In some cases, a writer might have a fairly clear idea in mind where the story is headed, or already be aware of certain key scenes that ought to be included. In others, the author may not know how the story ends(more…)

Events propel narrative. Narrative consists of a chain of events.

These do not have to be spectacular action events – they can be internal psychological events if your story is about a man who does not leave his room, or spiritual events if you are recounting the story of Buddha sitting beneath the tree. But events there must be if there is to be a story.

In this post we’ll discuss –

Events in a story are effectively bits of knowledge the author wants to impart – in a particular order, the narrative – to the recipient, i.e. the reader or audience. The story is told when all the pertinent knowledge has been presented, when all the bits of information necessary for the story to feel like a coherent unity are conveyed. An author(more…)

This may seem like a silly question. How long is a piece of string, right? And the simple answer is:

ideally, a story is as long as it needs to be, and no longer.

There are norms that have developed over time, and which are more or less inculcated into us due to our exposure to stories in their typical media. Back in the 1970s or 80s a music album contained a total of about 40 minutes of sound, because that is as much as would fit on a long-playing vinyl 33 rpm record, approximately 20 minutes on either side. With the advent of the CD, suddenly musicians felt the artistic need to create albums that were twice as long.

You’d think that stories wouldn’t be subject to such constraints because the carrier media for stories are more flexible. However, when it comes to moving pictures at least, what is typically considered a fair attention span to expect the audience to tolerate does seem prone to popular beliefs by industry players in the respective markets. For example, a typical feature length film is roughly two hours long. This is practical because cinemas can comfortably manage two screenings an evening. If the film is good enough, it could of course easily be longer, but at some point viewers become restless and need an intermission.

A typical two hour-ish movie has between forty and sixty scenes. Formatted according to industry standards, a screenplay has approximately as many pages as the finished movie would have minutes. In terms of plot events, some people in Hollywood believe that a commercial movie should have exactly forty (which in Beemgee’s plot outlining tool would mean exactly 40 event cards).

Content and form may be mutually determined, to some degree at least. A short story is usually considered such if it has less than 10.000 words. By dint of its length, a short story probably concentrates on one character’s dealing with one specific issue or occurrence, and is unlikely to have subplots or multiplots (that is, be about more than one protagonist).

Short stories are great practice for writers cutting their teeth. Our friends at the self-publishingschool have gathered 11 Easy Steps for Satisfying Stories.

A piece of written prose fiction between 10.000 and 50.000 words is often considered a ‘novella’. This is a sort of hybrid between the short story and the novel. The narrative of a novella is likely to cover more ground – that is, relate a longer and more complex set of events – than a short story simply because it is longer than a short story. But to state that a novella perforce has more depth or more action than a short story would be a meaningless generalization. What is likely is that the focus in a longer narrative such as a novella is on a string of occurrences (or chain of events, i.e. causally linked events) rather than the story revolving around the meaning and effects of a single occurrence. (more…)