Dramaturgical techniques in news stories.

This post is adapted from a longer piece by one of our founders on his personal Substack. Read the full article here (just click “no thanks” if you don’t want to subscribe).

If we’re watching a movie or reading a novel, we want a good story that reaches us on an emotional level. We demand to be excited, moved, aroused, even outraged or scared witless.

People enjoy the emotions that stories provoke. Emotional responses are the reason we succumb to stories, and storytellers deliberately try to elicit the “visceral” effect that powerful feelings engender. In order to root for the heroine, she must be placed in danger; in order to empathise with the hero, the audience must be able to identify with him and care about his fate. Writers and storytellers do a lot to engage the audience and keep them reading or viewing. The best techniques to maintain the audience’ attention are the ones that grab the audience emotionally. Stir them! Excite them! Make them feel! Boredom sets in when there is no increased heart rate, no sweaty palms, no rapt attention.

“Our top story tonight: …”

Newspapers and other news media such as television or online news portals know as well as novelists and moviemakers that the promise of emotion is what gets the audience’ attention in the first place and the delivery of emotion is what maintains it. Hence news media employ some similar techniques to fiction authors and screenwriters. Not for nothing is a news show or paper divided into “stories”. (more…)

A story has a beginning, a middle, and an end. How to avoid the ‘saggy middle’.

The middle bit of a story is really the story proper. It is usually the longest section. It comes after the introduction of the main character(s) and the setting up of the context, that is the world of the story, as well as the problems and themes the story deals with.

At the end of the first section – prior to what we’re here calling ‘the middle bit’ –, the protagonist has decided to set off on the story journey. Obviously, this does not have to be physical journey through a particular geography, but it does mean that the main character is somehow entering into new and unfamiliar terrain. In this sense, every story is a ‘fish out of water’ story. The heroine must leave the comfort zone in order for the audience to feel interest in her plight.

Some authors jump right into this unfamiliar territory, showing the run up to it in flashbacks. Anita Brookner’s heroine Edith Hope has already arrived in the Hotel du Lac in the first sentence of the novel. Gradually the reasons for her stay here are revealed as the reader progresses through the novel.

Nonetheless, for an author, it may be advisable to create a marked threshold where the protagonist enters into the alien territory of the middle bit. The exploration and transversal of this territory is what on a plot level the middle bit is about, and it takes up the greater part of the story journey. (more…)

The midpoint is structurally the most significant point in a narrative.

Given that stories have a tendency to symmetry, the centre of a narrative should mark the zenith of the story arc, and with that, the pivotal point of the story.

So, to get to (mid)point: What happens in the middle of a story?

Here are some typical midpoint events:

- Something searched for is found (Star Wars IV, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Lolita)

- A hidden truth is unveiled (to the audience, at least) – if not yet understood (Matrix, Pride and Prejudice, The Gruffalo)

- A dramatic event thwarts all plans made hitherto (James Cameron’s Titanic)

The centre of the narrative may be the discovery of something missing – in crime stories a vital piece of the puzzle may be revealed here (either to the audience or to the audience as well as the protagonist).

In any genre or dramatic category, the midpoint may be a moment of truth. This might be just a clue for the audience or perhaps an initial revelation of the true state of things.

If a character realises or finds out something that has so far been hidden, then this is the point at which the character begins to gain awareness. This counts in particular for the recognition of the character’s own internal problem. From here on the story might possibly lead up to a moment of choice at the crisis, when it becomes clear to the audience whether the character has learnt from this new awareness or not. In other words, the real need begins to overcome or supplant the character’s initial want due to what happens at the midpoint.

Some well-known examples of the midpoint

(more…)

Today’s guest post is by author Stefan Emunds.

Today’s guest post is by author Stefan Emunds.

Stefan’s favorite genre is visionary fiction – stories that have an enlightenment dimension. Enlightenment and storytelling have interesting parallels, which prompted Stefan to write a book about storytelling – The Eight Crafts of Writing.

Get a glimpse of his approach to story craft in his article.

Art and Craft

Storytelling is both art and craft, authoring and writing, plotting and pantsing.

1.1 Art and Authoring

Art is creativity. Creativity requires receptivity to the Muse and its inspirations.

Inspirations arrive as thought-images, which writers put into words. How to turn thought-images into words and assemble those into a structured story with vivid characters and an engrossing world is a matter of craft and skill.

1.2 Craft and Writing

The literal meaning of Kung Fu is a discipline achieved through hard work and persistent practice. Writing is Kung Fu.

Craft gives form to inspirations. Forms limit. Writers love the artistic side of writing, less so crafting, in particular, Story Outline. Writers are prone to procrastinate crafting.

But no limitations, no story. No canvas, no painting. No net, no tennis.

Understanding the difference between freedom and dominion helps to appreciate the constraints of craft. Freedom is a means to an end. We want to be free to do something, for example, to write a book. That’s all there is to freedom. Dominion, on the other hand, is mastery of structure. (more…)

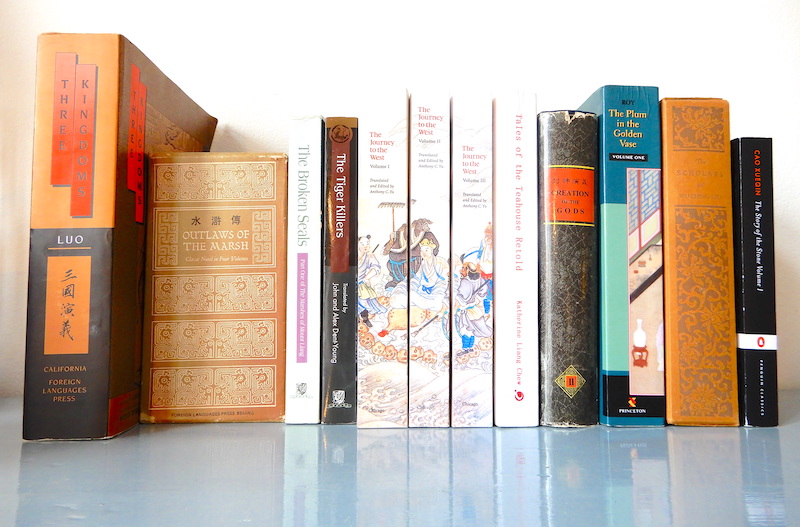

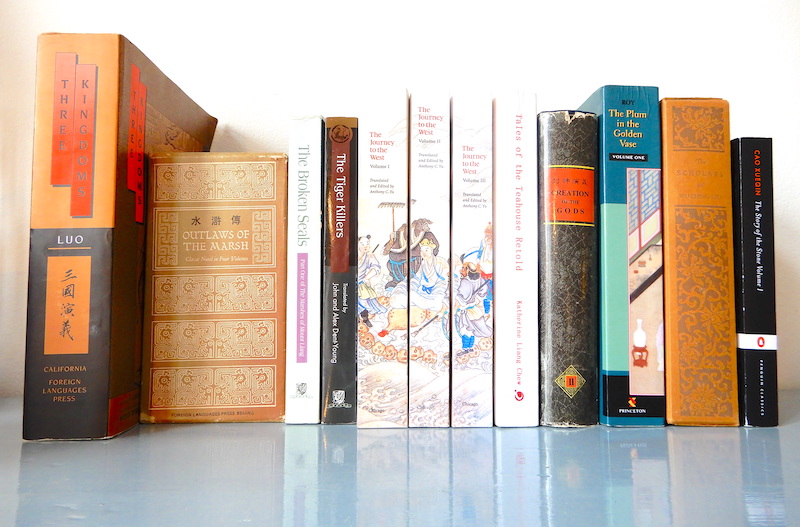

Take a look at your book shelf. Chances are there are European and North American authors there. Perhaps you have some Central or South American writers too. And maybe some Indian or Pakistani novels. And perhaps some Russians.

All of these authors wrote or write in the tradition of European storytelling, via colonial or cultural influence. Modern African authors writing novels, for example, have adopted this written prose text form although African storytelling traditions are primarily oral.

What most of us, at least in the western world, know about how to tell stories is influenced heavily by Aristotle’s Poetics. In this rather thin book, Aristotle describes some basic precepts of dramatic composition that continue to be circulated in creative writing classes and how-to books today.

Another strong influence on western storytelling is the protagonist/antagonist duality which arose along with Christianity. Would there be a Sauron without Satan? A Darth without the Devil? A Voldemort without Lucifer?

So what about stories that were created without any knowledge of Aristotle or Christianity? How are stories that had no contact with the western way of composing narratives different?

Let’s find out by asking … (more…)

Nothing should be more important to an author than how their story makes the audience feel.

As an author, consider carefully the emotional journey of the reader or viewer as they progress through your narrative.

The audience experiences a sequence of emotions when engaged in a narrative. So narrative structure is a vital aspect of storytelling. The story should be touching the audience emotionally during every scene. Furthermore, each new scene should evoke a new feeling in order to remain fresh and surprising.

The author’s job is to make the audience feel empathy with the characters quickly, so that an emotional response to the characters’ situation is possible. Only this can lead to physical reactions like accelerated heartbeat when the story gets exciting. We have to care.

This “capturing” of the audience, making the reader or viewer rapt and enthralled, requires authors to create events that will show who the characters are and how they react to the problems they must face. The audience is more likely to feel with the characters as the plot unfolds when the characters’ reactions to events reveal something about who they really are – and how they might be similar to us.

One Journey to Spellbind Them All

Here we present a loose pattern that we think probably fits for any type of story, whatever genre or medium, however “literary” or “commercial”. It’s not prescriptive, just a rough checklist of the stages in the emotional journey the audience tacitly expects when they let themselves in on a story. The emotions are in more or less the order they might be evoked by any narrative.

Curiosity

(more…)

Stories are driven by yearning.

In order to get somewhere, there has to be a current position and a destination. Stories fundamentally describe a change of state – things are different at the end of the story than at the beginning. Hence a story has a starting point and a final end point, a resolution.

But that’s not enough. There has to be fuel, energy to power the motion between the one position and the other. In stories, this driving force is the motivation of the characters.

Motivation is so important to storytelling that we are going to look at several aspects of it. We’ll break it down into what we call the wish, the want, and the goal, all of which are interlinked but also distinct from each other. Here in this post, we’ll deal with the wish.

A wish is inherent in the character from the beginning. We might call it a character want, as distinct from a plot want (which we deal with elsewhere).

Some examples: (more…)

Action is character.

So the old storytelling adage. What does that mean, exactly?

In this post, we’ll consider:

- The central or pivotal action – the midpoint

- Actions – what the character does

- Reluctance

- Need

- Character and Archetype

The central or pivotal action – the midpoint

More or less explicitly, the main character of a story is likely to have some sort of task to complete. The task is generally the verb to the noun of the goal – rescue the princess, steal the diamond. The character thinks that by achieving the goal, he or she will get what they want, which is typically a state free of a problem the character is posed at the beginning of the story.

The action is what, specifically, the character does in order to achieve the goal (rescue the princess, steal the diamond). In many cases, this action takes place in a central scene. Central not only in importance, but central in the sense of being in the middle.

Let’s look at some examples. (more…)

What’s the problem? Does the character know?

In storytelling, discrepancy between a character’s awareness and the awareness-levels of others is one of the most powerful devices an author can use. “Others” refers here not just to other characters, but to the narrator and – most significantly – to the audience/reader.

Let’s sum up potential differences in knowledge or awareness:

- A character’s awareness of his or her own internal problem or motivation

- A difference between one character’s knowledge of what’s going on and another’s

- The narrator knows more about what is going on than the character

- The audience/reader knows more than the character – dramatic irony

In this post, we’ll concentrate on the first point: Awareness of the internal problem. We’ll break that down into

- Becoming Aware – the importance of the revelation

- The Story Journey – and where to place the revelation

- Surface Structure and Deep Structure

- The Need for Awareness – or, Alternatives to Revelation

Becoming Aware – the importance of the revelation (more…)