Guest post by Ali Luke.

Ali Luke is a freelance writer and novelist who blogs about making the most of your writing time at Aliventures. For her best tips on making time to write, sign up for her email newsletter: you’ll receive a free copy of her mini ebook Time to Write: How to Fit More Writing Into Your Busy Life, Right Now.

Ali Luke is a freelance writer and novelist who blogs about making the most of your writing time at Aliventures. For her best tips on making time to write, sign up for her email newsletter: you’ll receive a free copy of her mini ebook Time to Write: How to Fit More Writing Into Your Busy Life, Right Now.

Pacing in fiction is how quickly—or slowly—the story progresses. The right pace for a story depends on its genre. If you’re reading a thriller, you’ll expect a fast-paced read with lots of action; if you’re reading a historical novel or epic fantasy, you might enjoy a slower pace with lots of emphasis on the world of the story.

It’s tough to get pacing spot-on when you’re drafting. It might take you years to write a book that takes just hours for someone to read. What feels “slow” to you as you write might actually go by pretty quickly on the page. Or, you may find that you repeat yourself, going over the same narrative ground multiple times, because you barely remembered what you wrote six months ago.

So, don’t worry about your pacing as you draft. Instead, address it in the redrafts—ideally, with the help of beta readers, but even simply reading over your full manuscript yourself can help you spot areas where the pace feels off.

Here’s what to look for when redrafting your work. (more…)

Some theorists have posited that stories are all about problem-solving. And certainly – as we have seen – problems are at the very core of story. So by giving the audience a chance to vicariously experience protagonists dealing with problems, a story is in effect a sort of playground or simulation where we can experience what potential problems and solutions feel like – but without any real-life consequences.

An important consideration here is cause and effect. In real life, what we experience has so many causes that it is well-nigh impossible to accurately pinpoint them all. We constantly feel the effects, but it’s hard to pinpoint all the causes. Nonetheless, we really like to have explanations for what’s going on, it gives us a greater sense of control over our own lives. As a species, we seek agency, we’re always looking for what caused something to happen, for the why behind things being as they are. We find it very confusing when we don’t know the reason for the events we live through, and we build elaborate mental constructs to explain to ourselves the world as we perceive it. In this context, we sometimes speak of “narratives”.

In stories, every scene must be the result of a preceding plot event. As we have said before, in between each plot event of a narrative you should be able to place the words not “and then”, but “because of that …”. (more…)

If you dont know what your story is really about, start finding out now (and don’t stop).

By Amos Ponger

Mankind’s Stories

The human ability of creating stories and the consumption and absorption of stories are very deeply connected to the core of our civilizations. Our efficiency as a species and cooperation in all scales of human endeavor rely on our ability to tell, decode, understand, and believe in stories.

Story has been so important for mankind’s cooperation, development and the way humans have understood themselves that all of our grand evolutions and revolutions – from the agricultural, religious, economic and cultural revolutions, the invention of money and law, the renaissance and humanism, the American, French and Russian revolutions, modernism, to socialism and capitalism – have actually happened through processes of rewriting collective Story. Revolutionaries and evolutionaries from Moses through Jesus, to Buddha, have actually risen upon a grand scale transformation of how humans understand themselves and cooperate with each other. And that has been done by story. Often the seeds of politics of whole centuries had actually been sown by poets, philosophers and prophets. STORYTELLERS.

Your Story

Now, even if you don’t plan on a revolution(more…)

by Amos Ponger

A pledge to transformational storytelling

Working for over 20 years as an award winning film editor and story consultant, Amos Ponger studied film science, cultural sciences, art history and multidisciplinary art sciences at The FU Berlin, Humboldt University Berlin and the Tel Aviv University. He has a Master’s degree from the Steve Tisch School of Film in the Tel Aviv University, worked as an editing teacher in two Israeli film academies, is senior advisor to our story development tool Beemgee.com, and recently co-founded the story consulting service Mrs Wulf. Book his services directly here.

The Transformational Process of Creating a Great Story

We all know that creating a great story is a process that can sometimes take many months and even years to fulfill.

If you talk to professional writers they will probably tell you that they have complex relationships with these processes of writing. Involving dilemmas, fear and joy, suffering and excitement. And that these self-reflexive processes are also processes of self-exploration.

Yet many writers, scriptwriters, filmmakers tend to put a lot of energy into their external journey towards completing their story, focusing on drama, act structure, “cliff hanging”, while neglecting minding their own internal processes on their journey.

What many film and story editors encounter while working with directors and writers is that authors and directors tend to have a very strong drive. They endure months in writing solitude, or filming in deserts, storms, war zones, perhaps even putting themselves in danger in order to realize their artistic vision. Yet at the same time very often they have a remarkable incapability of explaining WHY they HAVE to do it, and can only do so in very vague terms. (more…)

How narrative structure turns a story into an emotional experience.

Image: Comfreak, Pixabay

Storytelling is a bit of an overused buzzword. While we are all – by dint of being human – storytellers, how aware are you of the principles of dramaturgy? What exactly constitutes a story, in comparison to, say, a report or an anecdote?

And just to be clear, the following is not a story. It’s an how-to article.

Whatever the medium – film or text, online or offline –, storytelling has something to do with emotionally engaging an audience, that much seems clear. So is a picture of a cute puppy a story? Hardly.

Stories exist in order to create a difference in their audience. Stories always address problems and tend to convey the benefits of co-operative behaviour.

While there simply is no blueprint to how stories work, let’s examine the elements that recur in stories and try to find some patterns.

Who is the story about?

All stories are about someone. That someone does not have to be a person, it can be an animal (Bambi) or a robot (Wall-e). But a story needs a character. In fact, all stories have more than one character, with virtually no exceptions. This is because the interaction between several characters provides motivation, conflict and action.

Moreover, stories usually have a main character, the figure that the story seems to be principally about – the protagonist. It is not always obvious why one character is the protagonist rather than another. Is she simply the most heroic? Is she the one that develops most? Or does she just have the most scenes?(more…)

In stories, characters are faced with obstacles.

These obstacles come in various forms and degrees of magnitude. And they may have different dimensions: they may be internal, external, or antagonistic.

Often the obstacles that resound most with a significant proportion of the audience are the ones that force the main characters to face and deal with problems within themselves, in their nature. In other words, with their internal problem.

Internal obstacles are the symptoms of the characters’ flaws or shortcomings, i.e. of the internal problem. The audience perceives them in scenes in which the character’s flaw prevents her progress.

Not every story features characters with internal problems. An internal problem is not strictly speaking necessary in order to create an exciting story.

But it helps.

The Emotional Truth

An internal problem makes the character appear fallible – and thus more credible, more human, more like us. Internal problems are invariably emotional and private. They express(more…)

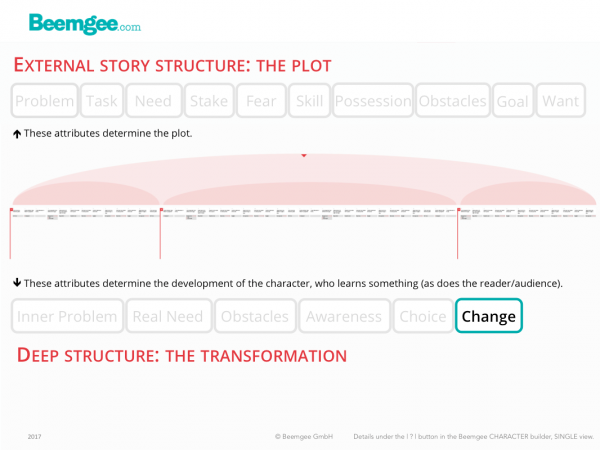

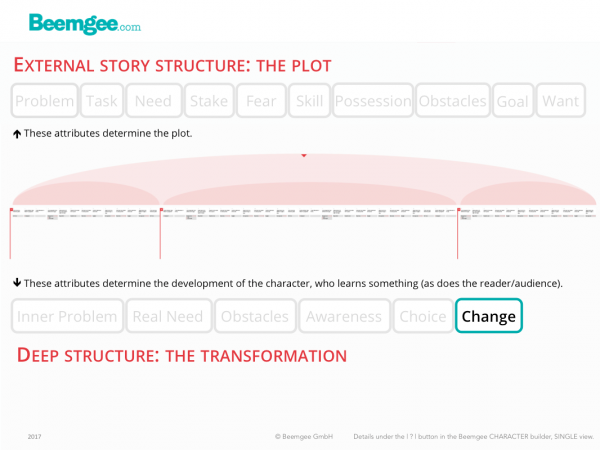

If there is one thing that ALL stories have in common, it is change.

A story, pretty much by definition, describes a change. Indeed, every single scene does.

Within a story, what changes?

At the very least,

- one of the characters, usually the protagonist

- often other characters too

- sometimes the whole story-world

- who understands what – the perception of what is true or valuable

1 – The protagonist changes

We have said before that a protagonist is usually wiser at the end of the story than at the beginning. We have seen that this has something to do with the want, which – whether the character achieves it or not – is usually only attainable by causing a change. Often the change involves the character’s solving the internal problem, so the change takes place within the character. This involves the recognition of the necessity for change, i.e. the acceptance of the real need, and the struggle to achieve it. So all the incidents and events in the plot, the hindrances and obstacles the characters deal with, are in themselves not so very interesting. What interests the audience more is how these events and obstacles change the character.

Having said that, a story may well show no more change than the solving of an external problem. A story world is disturbed, but at the end returns to a similar state. For instance in a detective story, where the crime is solved but the protagonist does not really develop.

2 – Several characters change

Characters don’t change in a vacuum. They learn through interactions with each other. Relationships cause change. In many stories, subplots will tell of the characters that surround the protagonist, and their changes and developments may well cast light on various aspects of the story’s theme. Or perhaps the story is an ensemble piece, where it is not easy (or even necessary) to identify a main protagonist. Or it is a romance, or buddy-story, which apparently has two main characters. Whichever – some level of change usually occurs in all the main characters as a result of how they interact with each other.

There is, by the way, one often neglected archetype who also typically changes. This role is sometimes referred to as foil. We call it the role of the contrastor. The contrastor mirrors and contrasts the protagonist, like Han Solo to Luke Skywalker in Star Wars or the mother to the boy in Boyhood.

3 – The whole world changes

Quite possibly, the entire story-world may be different by the end of the story than it was at the beginning. Story-world as a concept refers to the scope of the world presented in the story, so if the field of action of the characters is small, the story-world is small too. If the story is an epic, the story-world will be big, a version of an entire world.

As an aside on this last point, consider the classical genres. Epics – again, almost by definition – describe a change in a whole world. In a way, so does tragedy, for at the end of the tragedy the world will have lost one or more of its population, since tragedy deals with the change from life to death.

Comedy seeks to describe a different fundamental change in the story-world. The typical structure of comedy, whether we are talking about Aristophanes or modern TV sitcoms, has a stable situation at the beginning which is disturbed by some event or problem. The disturbance causes first a lot of messy but generally non-life-threatening chaos which is resolved by a return to the original undisturbed situation. Even if the main characters end up married, for example, the story-world is brought back to its stable state.

The very serious point of comedy is to demonstrate a fundamental truth: the cyclical nature of change in the universe. Spring always returns, no matter how bleak the winter. Day always comes, no matter how dark the night. Change does not have to be final. Change can be cyclical. Change is life.

4 – The Perception of Truth

The most fundamental change that stories tend to describe is one of recognition of truth. What is not known at the beginning of the story is recognised and thus becomes known at the end. This is obvious in crime stories, but holds true for almost all other stories too. The story therefore amounts to an act of learning. Often the learning curve is observable in the protagonist, who tends to be wiser at the end than at the beginning.

But the point is really that the recipient, the reader or viewer, is actually the one doing the learning – through experiencing the story.

The audience changes.

At least, that’s the general idea. The story provides a physical, emotional and intellectual experience – physical when your heart beats faster or your palms sweat, emotional when you feel for the characters, and perhaps intellectual too if the story gives you pause for thought. If the story achieves none of these responses, then it has failed. An experience, again pretty much by definition, changes you. We learn through experience; so if you have changed, chances are it’s because you have learnt something.

Hence it is not only within the story that a change takes place. It takes place outside of the story as well, in the recipient.

Within some stories one may argue that no real change occurs – Alice does not obviously change due to her experience in Wonderland. But the reader has been taken on a wild journey, and the experience is likely to have left some sort of mark.

How does a story provide an experience?

By allowing the recipient, the audience or reader, to understand and feel change and transformation throughout the story. Every scene describes a change. The entire narrative shows a difference between the “before and after”. Stories have a tendency to symmetry: The beginning of the story makes clear what the state of the protagonist or the story world is before the story journey commences, and the end of the story has a corresponding scene or event that shows what the state is after.

For the author, then, the task is to clearly know the state of things for the protagonist, the cast of characters, the story world, and the audience at the end of the tale, and the state of things at the beginning of the tale. The greater the contrast, the better. Once these two points of reference are known, the author works out the many steps needed to get the protagonist, the cast of characters, the story world, and the audience from one state to the other.

There is a paradox here. The change that occurs is also an expression of new equilibrium. At a very basic level, story structure can be described as follows:

- an external problem (a change in the ordinary world of the protagonist) disturbs the equilibrium of the initial situation

- the disturbance is explored, a struggle ensues in which obstacles must be overcome

- the problem is understood and dealt with, creating a new equilibrium or resolution

So change is all-pervasive in stories, within them in the form of character development, and without in the form of audience understanding. And that is not even to consider the transformational power of telling a story, when the act of telling the story brings about change in the author.

Read here how change is important for every single scene, though we prefer to call them plot events.

Related function in the Beemgee story development tool:

Character Developer

Not developing your story yet? Click here:

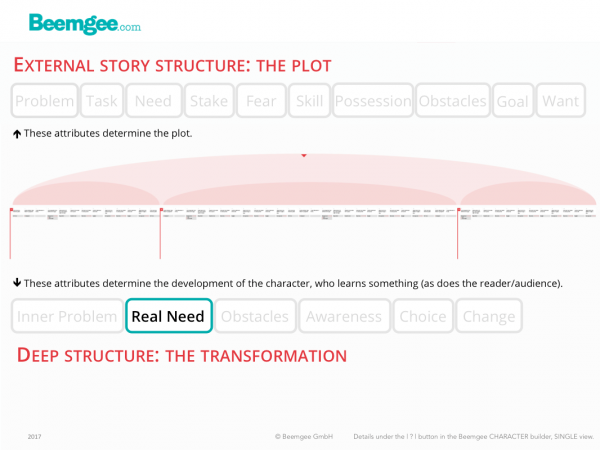

In most stories, what a character really needs is growth.

Characters display flaws or shortcomings near the beginning of the story as well as wants. What they really need to do in order to achieve what they want is likely to be something they need to become aware of first.

The real need relates to the internal problem in the same way the perceived need relates to the external problem. The character has some sort of dysfunction that really needs to be repaired.

That means the audience or reader may become aware of a character’s real need long before the character does. Most stories are about learning, and learning entails the uncovering of something previously unknown. So the real need of a character is to uncover the internal problem, to become aware of their flaw.

A character may be unaware of their real need because they are suppressing a secret from their past. Something they did (better than something that happened to them) causes shame or guilt and they therefore hide it from themselves. To get over this, they must achieve some sort of healing. The trick is to dramatise such inner conflict through plot events.

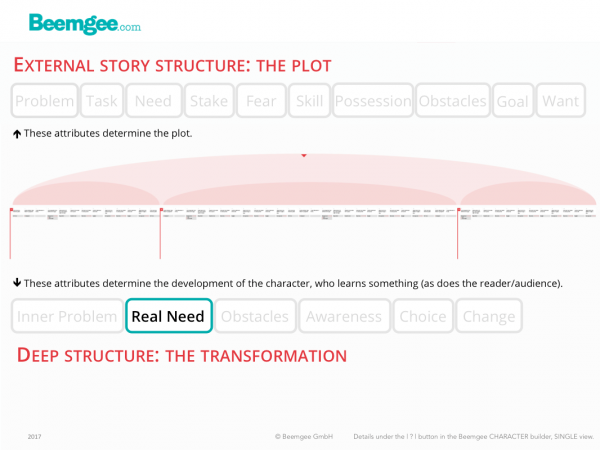

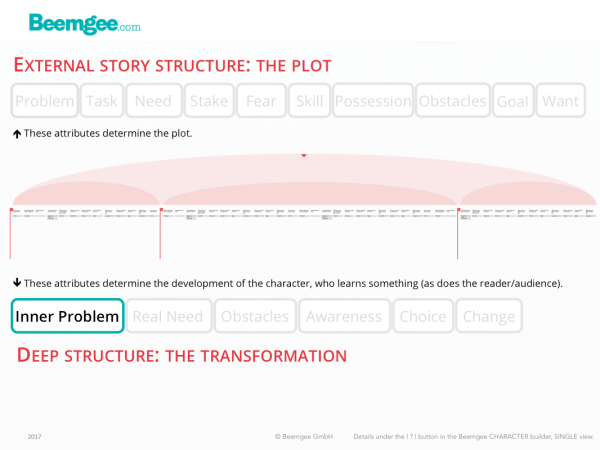

To recap: The usual mode in storytelling has a character consciously responding to an external problem with a want, a goal, and a number of perceived needs. Unconsciously, that character may well have a character trait that amounts to an internal problem, out of which arises that character’s real need – i.e. to solve the internal problem.

So if a character is selfish, the real need is to learn selflessness. If the character is overly proud, then he or she needs to gain some humility. In the movie Chef, the father neglects his son emotionally – his real need is to learn to involve the child in his own life. The audience sees this way before the Chef does.

Even stories in which the external problem provides the entertainment – and with that the raison d’être of the story – may profit from(more…)

What’s the problem? Does the character know?

In storytelling, discrepancy between a character’s awareness and the awareness-levels of others is one of the most powerful devices an author can use. “Others” refers here not just to other characters, but to the narrator and – most significantly – to the audience/reader.

Let’s sum up potential differences in knowledge or awareness:

- A character’s awareness of his or her own internal problem or motivation

- A difference between one character’s knowledge of what’s going on and another’s

- The narrator knows more about what is going on than the character

- The audience/reader knows more than the character – dramatic irony

In this post, we’ll concentrate on the first point: Awareness of the internal problem. We’ll break that down into

- Becoming Aware – the importance of the revelation

- The Story Journey – and where to place the revelation

- Surface Structure and Deep Structure

- The Need for Awareness – or, Alternatives to Revelation

Becoming Aware – the importance of the revelation (more…)

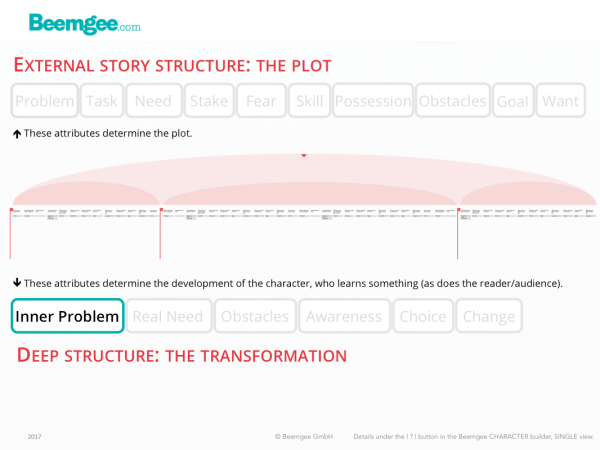

An inner or internal problem is the chance for change.

While the external problem shows the audience the character’s motivation to act (he or she wants to solve the problem), it is the internal problem that gives the character depth.

In storytelling, the internal problem is a character’s weakness, flaw, lack, shortcoming, failure, dysfunction, error, miscalculation, unresolved issue, or mistake. It is often manifested to the audience through a negative character trait. Classically, this flaw may be one of excess, such as too much pride. Almost always, the internal problem involves egoism. By overcoming it, the character will be wiser at the end of the story than at the beginning. Thus the character must learn cooperative behaviour in order to be a mature, socially functioning person.

The inner problem is the pre-condition for the character’s transformation. It is the flaw, weakness, mistake, error, or deficit that needs to be fixed. In other words, it shows what the character needs to learn.

Internal problems may be character traits that cause harm or hurt to others. They cause anti-social behaviour. And internal problems can also harm the character. They can be detrimental to his or her solving the external problem.

From Lack of Awareness to Revelation

While the external problem provides a character’s want, i.e. motivation, the internal problem provides the need.

The audience sees the flaw before the character does. The character is blinkered, has a blind spot. She first has to learn to see what the audience already knows. (more…)

Ali Luke is a freelance writer and novelist who blogs about making the most of your writing time at Aliventures. For her best tips on making time to write, sign up for her email newsletter: you’ll receive a free copy of her mini ebook Time to Write: How to Fit More Writing Into Your Busy Life, Right Now.

Ali Luke is a freelance writer and novelist who blogs about making the most of your writing time at Aliventures. For her best tips on making time to write, sign up for her email newsletter: you’ll receive a free copy of her mini ebook Time to Write: How to Fit More Writing Into Your Busy Life, Right Now.