If you dont know what your story is really about, start finding out now (and don’t stop).

By Amos Ponger

Mankind’s Stories

The human ability of creating stories and the consumption and absorption of stories are very deeply connected to the core of our civilizations. Our efficiency as a species and cooperation in all scales of human endeavor rely on our ability to tell, decode, understand, and believe in stories.

Story has been so important for mankind’s cooperation, development and the way humans have understood themselves that all of our grand evolutions and revolutions – from the agricultural, religious, economic and cultural revolutions, the invention of money and law, the renaissance and humanism, the American, French and Russian revolutions, modernism, to socialism and capitalism – have actually happened through processes of rewriting collective Story. Revolutionaries and evolutionaries from Moses through Jesus, to Buddha, have actually risen upon a grand scale transformation of how humans understand themselves and cooperate with each other. And that has been done by story. Often the seeds of politics of whole centuries had actually been sown by poets, philosophers and prophets. STORYTELLERS.

Your Story

Now, even if you don’t plan on a revolution(more…)

What does meaning mean? When is a tale meaningful? A few perspectives on imbuing your plot and characters with a subtext.

It’s no mean feat to make your audience feel they have learned something through your story.

Meaning is that which is intended or understood. The audience draws significance, relevance or profundity out of a story when it understands the deeper implications, reasonings and causes behind it. The meaning of a story depends on the standpoint. An author may mean something different from what the audience understands.

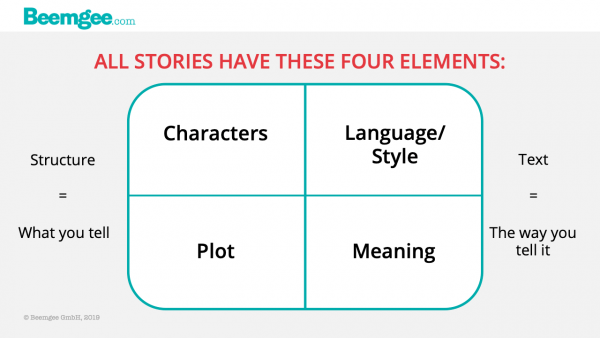

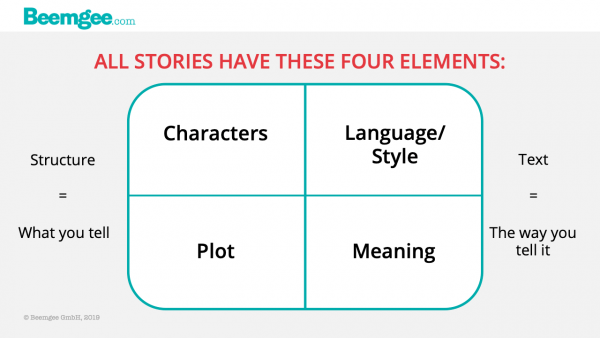

Let’s try to unravel this tricky but essential element of stories. We have noted that stories cannot help but exhibit four distinct elements:

- Characters

- Plot

- Style (aka language, or “voice”)

- Meaning

The interplay of characters and their actions form the plot, and all this is brought into a story structure, or narrative. Since there is always an author writing the novel or a team of people making the film, their stylistic choices determine the language of the work. In this post, we’ll skim the surface of the fourth element. Meaning is, of course, a broad term for something very hard to pinpoint.

We could add more story elements to the list. For instance, we have claimed that there is No Story Without Backstory. Furthermore, since the characters act within a time and place, there is always a story world. And in order to make the audience understand all this, there is always some measure of exposition. Then there is change or transformation, cause and effect, etc.

Let’s break down how we might look for the meaning of a story. (more…)

The term motif refers to any recurring element – in storytelling as in music or other arts.

Examples of elements that turn up repeatedly within a whole are an image on a tapestry or a particular sequence of notes in a symphony. The dispersal of these elements creates a pattern. It is therefore part of the artist’s craft to have some sort of design principle determine this pattern.

What motifs do

Motifs do not make a plot. But since they make patterns they are part of the structure of a story. And they help add a layer of meaning.

In other words, if a motif is present excessively in the first half of a story, and hardly at all in the second, then the author had better be aware of a reason for this uneven distribution. The distribution – the pattern – carries meaning to the audience. Remember, the audience yearns for meaning, is always striving to understand what the story is trying to convey at any given point. This demand for some sort of raison d’être for each element of a story, or for a sense of order within the whole, may well be unconscious to the audience much of the time, but ultimately the experience of the story is more satisfying when the audience can work out reasons and meaning.

In stories, motifs can be almost anything. Objects, actions, metaphors, symbols, colours, or images can be motifs. What defines an element as a motif is the systematic deployment within the story rather than the thing itself.

How motifs work

Motifs work best when(more…)

Welcome to the Beemgee blog.

This blog is about storytelling and story development. We examine how fiction works and what stories really consist of, concentrating especially on plot and character development. Many of the posts are inspired by functions and features of our outlining software. It’s all about the craft of creating stories. (more…)

This may seem like a silly question. How long is a piece of string, right? And the simple answer is:

ideally, a story is as long as it needs to be, and no longer.

There are norms that have developed over time, and which are more or less inculcated into us due to our exposure to stories in their typical media. Back in the 1970s or 80s a music album contained a total of about 40 minutes of sound, because that is as much as would fit on a long-playing vinyl 33 rpm record, approximately 20 minutes on either side. With the advent of the CD, suddenly musicians felt the artistic need to create albums that were twice as long.

You’d think that stories wouldn’t be subject to such constraints because the carrier media for stories are more flexible. However, when it comes to moving pictures at least, what is typically considered a fair attention span to expect the audience to tolerate does seem prone to popular beliefs by industry players in the respective markets. For example, a typical feature length film is roughly two hours long. This is practical because cinemas can comfortably manage two screenings an evening. If the film is good enough, it could of course easily be longer, but at some point viewers become restless and need an intermission.

A typical two hour-ish movie has between forty and sixty scenes. Formatted according to industry standards, a screenplay has approximately as many pages as the finished movie would have minutes. In terms of plot events, some people in Hollywood believe that a commercial movie should have exactly forty (which in Beemgee’s plot outlining tool would mean exactly 40 event cards).

Content and form may be mutually determined, to some degree at least. A short story is usually considered such if it has less than 10.000 words. By dint of its length, a short story probably concentrates on one character’s dealing with one specific issue or occurrence, and is unlikely to have subplots or multiplots (that is, be about more than one protagonist).

Short stories are great practice for writers cutting their teeth. Our friends at the self-publishingschool have gathered 11 Easy Steps for Satisfying Stories.

A piece of written prose fiction between 10.000 and 50.000 words is often considered a ‘novella’. This is a sort of hybrid between the short story and the novel. The narrative of a novella is likely to cover more ground – that is, relate a longer and more complex set of events – than a short story simply because it is longer than a short story. But to state that a novella perforce has more depth or more action than a short story would be a meaningless generalization. What is likely is that the focus in a longer narrative such as a novella is on a string of occurrences (or chain of events, i.e. causally linked events) rather than the story revolving around the meaning and effects of a single occurrence. (more…)

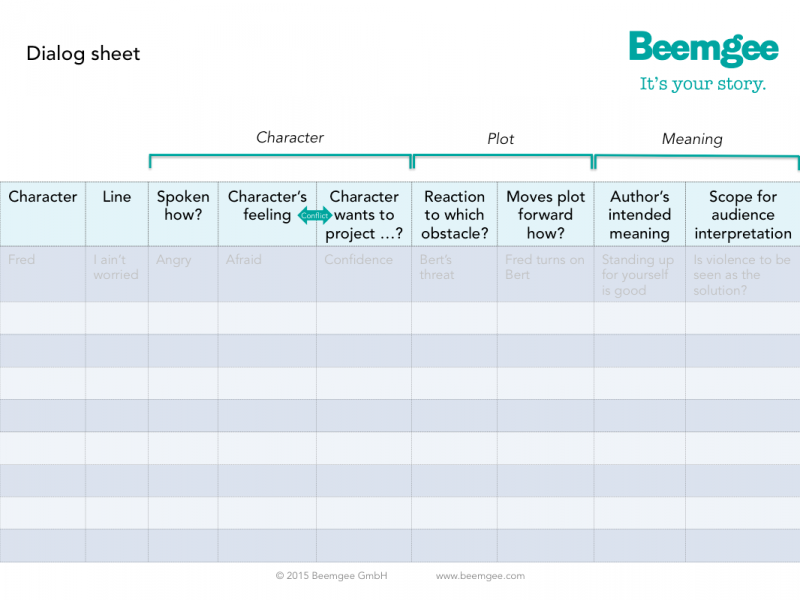

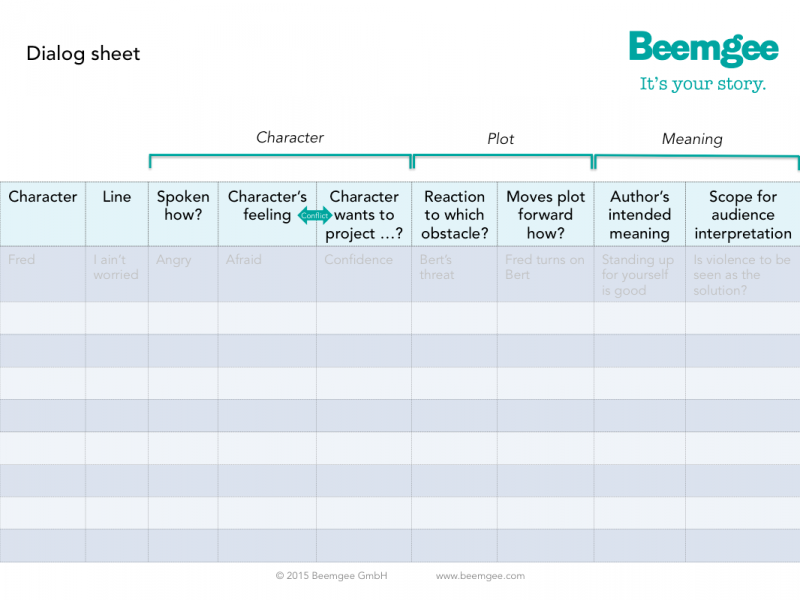

The seven elements of every line of dialog in a story.

Dialog enlivens stories. But dialog in stories is very different from real spoken language. It conveys information that the audience needs to know in order to understand the story as well as the characters – the one speaking the lines as well as the one reacting to them.

There is the rule of thumb that it’s better for the author to use action to explain things or move the plot forward than dialog, at least in film. Certainly, when the author makes characters say things solely to convey some bit of knowledge to the audience or reader, the lines tend to feel false. That’s a form of exposition, explanatory stuffing. If in doubt, leave it out. You’ll be surprised how much the audience understands even without explanations.

On the other hand, Elmore Leonard noted how readers don’t usually skip dialog. People like dialog. Dialog can be exciting. Dialog can be action. So authors had better know how to write it.

Here are seven things you ought to consider about every single line of dialog you put into your characters’ mouths. We’ve created this free table to help you. Feel free to download, use and share it.

1

If you’re writing(more…)

There is a craft to storytelling.

Much of the craft behind fabulation has to do with structuring the story being told, the construction and organisation of its narrative. Many authors design this construction first, before filling the first page with text. The process of planning how the story works is known as outlining.

There are significant benefits to outlining. For one thing, going through this process usually entails fewer rewrites later. When the author knows the direction of the storyline, it is easier to keep all its threads under control while writing. Without this direction, there is a danger of losing the plot half way through.

Stories have structure. (more…)