How perceptive a character is of her surroundings may have dramaturgical relevance.

A character who is good at noticing small details may make a good spy or detective, so if you are developing a detective or spy you may want to give your character this ability. But whatever your character’s profession, stop at least once per scene and ask yourself,

What is a detail that only this character might notice?

Why is this important? Because their perceptions can make characters more interesting and vivid.

If a certain plot event hinges on a character perceiving some small detail or other, it may be a good idea to plant a foreshadowing moment long before the scene, to heighten the impact of the act of perception.

Furthermore, a character’s perception may influence how your audience understands and enjoys the entire story. How exactly depends on two important factors:

- narrator

- point of view

(more…)

Creation Takes Time.

This is an age of faster, faster, more, more. At the latest since the advent of the internet, everything seems to be speeding up. Processes that took weeks a few decades ago now take only a few hours, things that in the twentieth century took hours now take place within minutes or seconds. You can get from A to B in less time than ever. The requirements on most of us for most of our work call for ever greater efficiency. We must not waste time. We must be quick.

Composing a story is a painstaking process. And yes, here at Beemgee we built our fiction tool in order to make the process of composing a story more efficient. We want to make it easier to organise a plot and determine the characters’ motivations – for the authors themselves, and for all the people communicating about the story, so between interested parties such as authors and their editors or screenwriters and producers.

But though we might want our authors’ efficiency to increase, let’s not kid ourselves. Composing a story is still a painstaking process. Because most of the time is spent thinking.

Thinking takes time. And that is mostly what plotting and outlining a story really is, thinking. (more…)

Here at Beemgee, we’re into the thought behind the writing of stories more than the writing itself. So we’re all the more pleased that Writer.com approached us to talk about character development. While their speciality is AI-assisted text generation for companies, in their guest post, they have some good general advice on creating fictional characters. Thanks to Nicholas Rubright for this article. Nickolas is a digital marketing specialist and expert at Writer. In his free time, he enjoys playing guitar, writing music, and building cool things on the internet.

Here at Beemgee, we’re into the thought behind the writing of stories more than the writing itself. So we’re all the more pleased that Writer.com approached us to talk about character development. While their speciality is AI-assisted text generation for companies, in their guest post, they have some good general advice on creating fictional characters. Thanks to Nicholas Rubright for this article. Nickolas is a digital marketing specialist and expert at Writer. In his free time, he enjoys playing guitar, writing music, and building cool things on the internet.

Writing characters with whom readers can identify and empathize should be the goal of every writer, but it’s not a simple task.

To fully grasp a character’s motivations, desires, and anxieties, writers must dive deep into the character’s psyche. Character flaws and strengths work together to build a solid character.

But what is the most effective way to develop a character? And how can you establish a connection between your character’s dramatic decisions and the story itself?

Your characters are the heart and soul of your story. Thus, before you can write a single word, you must first understand your characters.

When it comes to character creation, you have several choices to make, and each choice affects the story in its own way. You must, however, choose what works best for your character.

While an unexpected detail can make the character more interesting, if it isn’t chosen carefully it can damage the character’s believability and ruin your reader’s immersion in your story.

Here are some guidelines and tricks to help you successfully create mouldable character templates for your story.

So, let’s dive in! (more…)

What a character might know that others don’t – including the audience

Some characters have secrets. We are not necessarily talking about their internal problem or the need that arises out of it (they may be aware of such a problem or not.) We are talking about information that makes a difference to the story once it is shared.

Character secrets are intimately bound to the scene type called a reveal (which does not necessarily have to entail a revelation).

In terms of story (or rather the dramaturgy of the story), if a character has a secret that is never revealed, the secret is irrelevant. Only if the secret is made known at some point in the narrative does it really exist as a component of the plot.

For authors, the main aspects of character secrets to control are:

- What plot event brings the secret about (this may be a backstory event)?

- How does the secret alter or determine the character’s decisions or behaviour?

- Does the character share the secret with another character at any point, and if so when (in which scene)?

- At what point in the narrative (in which scene) does the audience receive knowledge of this secret?

Who are you, really?

If it is so important the character has a secret, then, often, the secret becomes part of who this character is. Their role in the story, their identity within the story, is determined by their secret. So secrets are dramaturgically important. (more…)

Today’s guest post is by author Stefan Emunds.

Today’s guest post is by author Stefan Emunds.

Stefan’s favorite genre is visionary fiction – stories that have an enlightenment dimension. Enlightenment and storytelling have interesting parallels, which prompted Stefan to write a book about storytelling – The Eight Crafts of Writing.

Get a glimpse of his approach to story craft in his article.

Art and Craft

Storytelling is both art and craft, authoring and writing, plotting and pantsing.

1.1 Art and Authoring

Art is creativity. Creativity requires receptivity to the Muse and its inspirations.

Inspirations arrive as thought-images, which writers put into words. How to turn thought-images into words and assemble those into a structured story with vivid characters and an engrossing world is a matter of craft and skill.

1.2 Craft and Writing

The literal meaning of Kung Fu is a discipline achieved through hard work and persistent practice. Writing is Kung Fu.

Craft gives form to inspirations. Forms limit. Writers love the artistic side of writing, less so crafting, in particular, Story Outline. Writers are prone to procrastinate crafting.

But no limitations, no story. No canvas, no painting. No net, no tennis.

Understanding the difference between freedom and dominion helps to appreciate the constraints of craft. Freedom is a means to an end. We want to be free to do something, for example, to write a book. That’s all there is to freedom. Dominion, on the other hand, is mastery of structure. (more…)

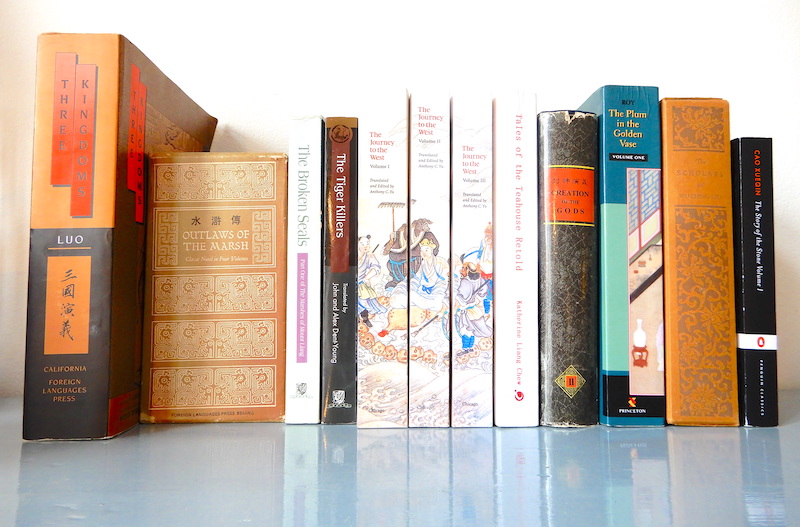

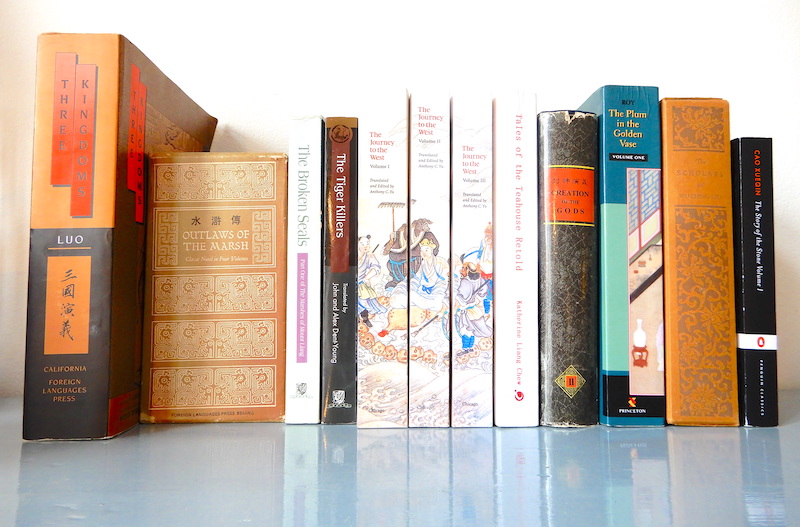

Take a look at your book shelf. Chances are there are European and North American authors there. Perhaps you have some Central or South American writers too. And maybe some Indian or Pakistani novels. And perhaps some Russians.

All of these authors wrote or write in the tradition of European storytelling, via colonial or cultural influence. Modern African authors writing novels, for example, have adopted this written prose text form although African storytelling traditions are primarily oral.

What most of us, at least in the western world, know about how to tell stories is influenced heavily by Aristotle’s Poetics. In this rather thin book, Aristotle describes some basic precepts of dramatic composition that continue to be circulated in creative writing classes and how-to books today.

Another strong influence on western storytelling is the protagonist/antagonist duality which arose along with Christianity. Would there be a Sauron without Satan? A Darth without the Devil? A Voldemort without Lucifer?

So what about stories that were created without any knowledge of Aristotle or Christianity? How are stories that had no contact with the western way of composing narratives different?

Let’s find out by asking … (more…)

Nothing should be more important to an author than how their story makes the audience feel.

As an author, consider carefully the emotional journey of the reader or viewer as they progress through your narrative.

The audience experiences a sequence of emotions when engaged in a narrative. So narrative structure is a vital aspect of storytelling. The story should be touching the audience emotionally during every scene. Furthermore, each new scene should evoke a new feeling in order to remain fresh and surprising.

The author’s job is to make the audience feel empathy with the characters quickly, so that an emotional response to the characters’ situation is possible. Only this can lead to physical reactions like accelerated heartbeat when the story gets exciting. We have to care.

This “capturing” of the audience, making the reader or viewer rapt and enthralled, requires authors to create events that will show who the characters are and how they react to the problems they must face. The audience is more likely to feel with the characters as the plot unfolds when the characters’ reactions to events reveal something about who they really are – and how they might be similar to us.

One Journey to Spellbind Them All

Here we present a loose pattern that we think probably fits for any type of story, whatever genre or medium, however “literary” or “commercial”. It’s not prescriptive, just a rough checklist of the stages in the emotional journey the audience tacitly expects when they let themselves in on a story. The emotions are in more or less the order they might be evoked by any narrative.

Curiosity

(more…)

Guest Post by KT Mehra.

KT Mehra knows a thing or two about writing from her own experience, not only as an author but as a supplier to writers and authors of fine stationary, in particular fountain pens. Not only that, she is digital savvy too.

Back in 1999, KT and her husband Sal started a small web company to create websites for local businesses and provide internet access. They both had a passion for fountain pens, and one day KT, in an excess of enthusiasm, ordered far too many from a pen company. Just for fun, she decided not to return any of them and instead asked her team to design an e-commerce website to sell the extra pens.

To everyone’s surprise and just like that, the website came together quickly and was an instant success.

KT believes that in the modern digitally saturated world, it’s more important than ever to stay true to your thoughts and create something tangible. In that spirit of creation, she feels that something as elemental as putting pen to paper is ever more essential.

Despite offering a digital tool for authors, we couldn’t agree more!

Develop a romantic relationship that your readers will engage with and root for.

Most of the romance novels you love so much use certain secrets to hook their readers in and keep them engaged.

Learning the secrets to create such compelling romance novels will help you perfect your characters’ love story.

The Basics

The best way for your readers to relate and root for your relationship is for you to make it realistic and dynamic. To build the foundation of any great love story, you need to have a few things down first. (more…)

A blurb is a short text on the back of a paperback book designed to get you to purchase that book.

Received wisdom in the publishing industry has it that the cover design triggers browsing bookshoppers to pick up a particular book from the table, after which most people will turn it over to read what’s on the back. The short text on the back cover must then arouse so much interest about the content of the book that the impulse to purchase is triggered. Many customers might glance into the book first before actually going to the checkout.

The blurb text is also used to advertise the book in some print magazines and online shopping platforms. Again, the cover is likely to determine whether the blurb text gets read, but in most cases a sale is unlikely without the blurb having done its job of persuading the prospective customer that this is the right book for them.

Films also have blurbs, which are usually placed in combination with the film poster or a film still.

A blurb is therefore a marketing text. It is not a brief synopsis of the story! The blurb is not really designed to provide information, but to create interest. So the job of the blurb is actually to give just enough information to make withholding more information effective. Not saying quite as much as the recipient wants to know is how to arouse curiosity.

What this often boils down to is answering three key questions about the story in the blurb: (more…)

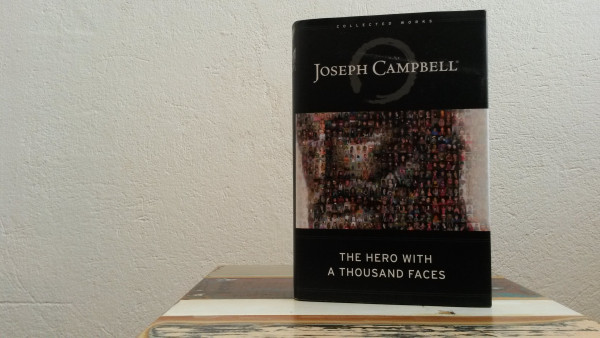

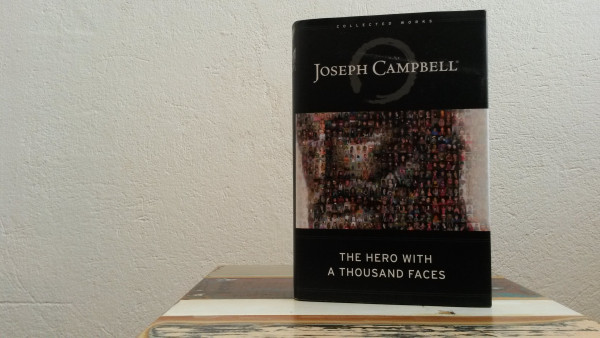

Joseph Campbell: The Hero With A Thousand Faces.

Joseph Campbell’s study of worldwide myths, The Hero With A Thousand Faces (1949), has become massively influential in commercial storytelling. Campbell was not the first to consider the concept of the hero and mythological or archetypal stories, and by no means the last (see Northrop Frye, as well as Robert Scholes and Robert Kellogg). But Campbell’s work consolidated what others, including Carl Jung, had suggested into a theory specifically about storytelling.

George Lucas read The Hero With A Thousand Faces as a young man, and we may assume that Francis Ford Coppola and Steven Spielberg were also familiar with the book. We can see the influence of Campbell’s ideas on some of the most successful movies of the 1970s and 80s, and ever since.

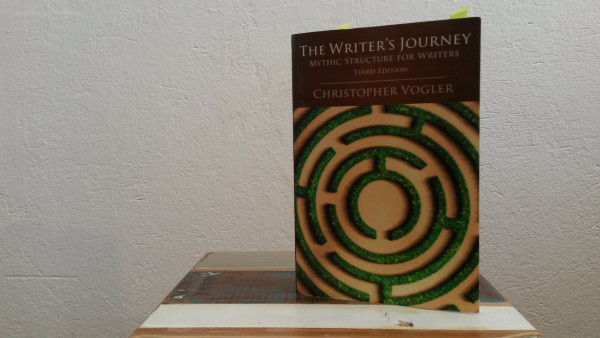

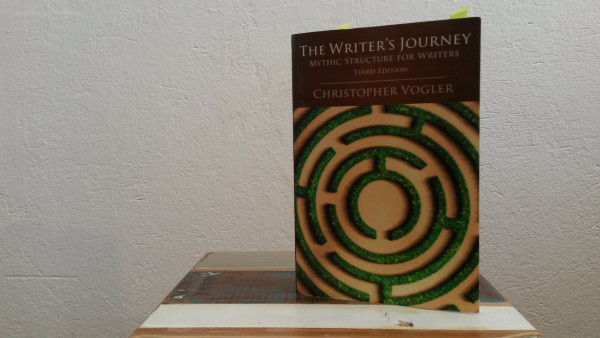

Christopher Vogler studied film at the same school as George Lucas, and subsequently while working at Disney wrote a seven-page breakdown of Campbell’s book. This in time developed into The Writer’s Journey, which has become the basis of the popular conception of The Hero’s Journey.

Campbell was an expert on James Joyce and a professor of literature with a particular interest in comparative mythology and comparative religion. The Hero With A Thousand Faces is by no means a how-to book or a storytelling manual. Rather, it posits the theory that all the myths of the world have elements in common and propounds the idea of the “monomyth” as a basic structural model of traditional storytelling. (more…)

Is there a recipe for successful stories?

In search of a recipe for success, Hollywood development executive Christopher Vogler wrote a seven-page practical guide for Disney to Joseph Campbell’s comparative analysis of worldwide myths.

George Lucas had already stated his debt to Campbell in the development of Star Wars, and the idea that there might be a template for stories that are so successful they last over centuries and across cultures caught on quickly in Tinseltown. (more…)

The essential elements of a story.

One of the many experts on storytelling to have attempted in a book to describe the essential elements of a story is John Truby.

In The Anatomy of Story (2007), Truby identifies 22 steps in any protagonist’s narrative, which may play into four aspects of the story: character, plot, story world, and moral argument. Thankfully, Truby does not insist that every story must follow the template strictly and contain all 22 steps. He does, however, identify as critical that the story show seven attributes of a main character and their storyline: (more…)

A synopsis is a summary of your story intended to be read by industry professionals.

This makes it a different text from a blurb, which is designed to be read by the public.

In both cases, you probably want the reader to purchase your story. But the reader of the blurb is merely buying a book or a movie ticket. The reader of the synopsis is taking a much greater risk if they decide to invest in your story.

An editor or publisher or a movie producer or director is accustomed to hearing story pitches. They want to find out as quickly as possible if your story is something that they might be interest in. So they need certain questions answered fast. These questions usually concern the premise(more…)

If you dont know what your story is really about, start finding out now (and don’t stop).

By Amos Ponger

Mankind’s Stories

The human ability of creating stories and the consumption and absorption of stories are very deeply connected to the core of our civilizations. Our efficiency as a species and cooperation in all scales of human endeavor rely on our ability to tell, decode, understand, and believe in stories.

Story has been so important for mankind’s cooperation, development and the way humans have understood themselves that all of our grand evolutions and revolutions – from the agricultural, religious, economic and cultural revolutions, the invention of money and law, the renaissance and humanism, the American, French and Russian revolutions, modernism, to socialism and capitalism – have actually happened through processes of rewriting collective Story. Revolutionaries and evolutionaries from Moses through Jesus, to Buddha, have actually risen upon a grand scale transformation of how humans understand themselves and cooperate with each other. And that has been done by story. Often the seeds of politics of whole centuries had actually been sown by poets, philosophers and prophets. STORYTELLERS.

Your Story

Now, even if you don’t plan on a revolution(more…)

Three sorts of opposition, and two things to remember.

Opposition causes conflict

For any character in a story, there may be opponents, not just for the protagonist. So while the protagonist-antagonism struggle may be at the forefront of the story, actually there is a whole system of opposing forces.

Let’s examine how characters in stories work against each other.

- Opposition can come from striving for the same or for opposite ends.

- Opponents can be antagonistic or incidental.

- There are two sorts of opponents, those from without, and those from within.

Same same or different?

An author might take each character at a time and arrange their opponents, which means characters who are either trying to get to the same thing first or whose success in attaining something else would thwart the character’s efforts.

In other words, the opposition (unless it arises by chance, see below) takes the form of either competition or threat. Competition for the same goal: Who will reach the South Pole first? Threat, because the goal of the opponent is opposed to the goal of the other figure: a nature reserve or a hotel complex. Imagine this for yourself using your own example: Your opponents strive for the same goal as you, and if your competitor wins, you get nothing. So your opponents are competing with you for the same goal, for example the same person. Or your opponent wants something completely different from you, and if he achieves that, it means you cannot get what you want. The success of the opponent is therefore a threat to your own well-being.

In either case, the opposition may be … (more…)

Why The Hero Is Never Alone.

Allies Embody the Principle of Cooperation

Despite their complexity and diversity, there are essentially only three different kinds of human relationships.

That’s right, if you take a step back and try to categorize human interactions, you’ll find three distinct types. Biologists know this, because the principle applies to any species that lives in groups. Within the group, three types of behavior may be observed:

- individuals cooperate with each other

- individuals compete with each other

- individuals mate

Evolutionary biologists describe a spectrum of individual to group selection. Some animals will typically try to maximize their individual gain, as exhibited in behaviors such as taking the biggest share of food or the best space for offspring, without regard for other animals in the group. On the other hand, some species have evolved social organizations in which individuals may act purely for the group’s benefit rather than individual gain. Think of ants, bees, or termites.

Interestingly, on this spectrum between profit maximization and altruism, homo sapiens sit pretty much exactly in the middle. Humans are genetically programmed to selfishness, to seek what is perceived as best for oneself and one’s immediate family, and at the same time have a strong and innate instinctive and natural urge towards cooperation and social behavior – which ultimately also increases our survival chances.

Cooperation, neighborliness, charitable behavior, acts of kindness – even if they costs us, they generally make us feel better and they make life in the tribe, clan, or community so much easier. Mind you, we do like to look after number one. We’re not going to simply give up our salaries, our homes, our lifestyles. Our own needs and those of our families come first. Who is not aware of this dichotomy?

The pull in opposite directions between egoism and altruism is perhaps one of the specifics of human beings as a species that has caused us to evolve abstract thought processes as well as complex societal and cultural forms. It also sheds light on basic principles of storytelling such as conflict. (more…)

Archetypal Antagonism in Documentary Film and Fiction

by Amos Ponger of Mrs Wulf Story Consulting

Stories are intricate mechanisms

Documentary film is a powerful genre that draws much of its energy from the material of real-life action. Consuming documentaries, we as spectators often ignore the fact that documentaries, like fiction, are a constructed clockwork of storytelling. Since the digital revolution, the amounts of raw material for documentary productions have probably grown tenfold, shifting much of the dramaturgical construction work to the editing room. Dealing with hundreds of hours of material you may say that 90 percent of the editing work in documentary film is “finding the story“, discovering what your story is about.

One issue editors often encounter while working on the narratives of documentary films is that many directors tend to neglect the importance of understanding and designing their antagonist or their antagonistic powers, the Antagonism.

Sure, you love your protagonists. You identify with their strivings and journeys, and you as a storyteller have probably given a lot of thought to making them appealing to your audience, giving the audience someone they can identify with. Your protagonists may be an inspiration to you, or you may yourself strongly identify with them, you may share or appreciate some of their characteristics and values.

At the same time you have probably not given your Antagonist/m the same attention. Have you? (more…)

How narrative structure turns a story into an emotional experience.

Image: Comfreak, Pixabay

Storytelling is a bit of an overused buzzword. While we are all – by dint of being human – storytellers, how aware are you of the principles of dramaturgy? What exactly constitutes a story, in comparison to, say, a report or an anecdote?

And just to be clear, the following is not a story. It’s an how-to article.

Whatever the medium – film or text, online or offline –, storytelling has something to do with emotionally engaging an audience, that much seems clear. So is a picture of a cute puppy a story? Hardly.

Stories exist in order to create a difference in their audience. Stories always address problems and tend to convey the benefits of co-operative behaviour.

While there simply is no blueprint to how stories work, let’s examine the elements that recur in stories and try to find some patterns.

Who is the story about?

All stories are about someone. That someone does not have to be a person, it can be an animal (Bambi) or a robot (Wall-e). But a story needs a character. In fact, all stories have more than one character, with virtually no exceptions. This is because the interaction between several characters provides motivation, conflict and action.

Moreover, stories usually have a main character, the figure that the story seems to be principally about – the protagonist. It is not always obvious why one character is the protagonist rather than another. Is she simply the most heroic? Is she the one that develops most? Or does she just have the most scenes?(more…)

Antje Tresp-Welte is the winner of the Your Perfect Plot challenge set by BoD and Beemgee.

In her guest blog post, she gives frank insight into her writing process and her experiences with Beemgee.

Short stories were child’s play

Short stories were child’s play

When something intrigues me, I spin a story out of it. Until a few years ago I wrote mostly fairy tales, short stories for adults, poetry and stories for younger children, some of which were published in magazines. My story about a bad-tempered spectacled snake was published as a little book, “Charlotte and the Blue Lurker”. For all these stories I only sketched a few thoughts as planning and then wrote them down relatively quickly.

By now, book projects fascinate me too. Currently they are crime novels and fantasy for children from 8 or 10 years.

Long takes longer …

During a holiday at the North Sea I had the idea for my first crime novel. In it, the protagonist, an eleven-year-old very imaginative boy with a penchant for drawing, not only saves his grandma’s tea room from demolition, but is also involved in a mysterious story about a pirate who died long ago. I developed the original idea into a plot at a seminar for authors. I found the topic so great that I couldn’t wait to start writing it. Beforehand, I made notes on the individual characters and considered important cornerstones of the plot with the help of the hero’s journey. I started off with a great momentum and was soon able to read the first chapters to my son. Unfortunately his comment was, “Mama, that is much too long!”

… not to be longwinded

My two test readers came to a similar conclusion and I too had noticed that it somehow “grated”. I wasn’t really getting to the point. Was it due to my preliminary planning? Was it not detailed enough? I dived into the text, shortened passages, removed individual characters and worked out others more precisely. This changed entire storylines. At the same time my story gained more (narrative) speed and I found the tone for the language. (more…)

The logline is probably the hardest sentence to write.

The logline sums up a story in one sentence. This sentence should be memorable and clear, which means it is unlikely to be much longer than thirty words or to have complex syntax.

Once your reader has read your logline – or your listener heard it –, they will ideally know the following about your story:

- who it is about

- what the central conflict or main problem is

- what the most important characters do in the story

- why they do it, i.e. what their motivations are

- how they do it

- where all this happens, i.e. what the setting is

- when it happens, i.e. what the period is

The first of these points even counts double – since usually the logline should convey not only who the main protagonist is, but also what antagonism she faces.

What’s the logline for?

The purpose of the logline is to pitch your story.(more…)

The protagonist is the main character or hero of the story.

Photo by Jack Moreh on Freerange

But “hero” is a word with adventurous connotations, so we’ll stick to the term protagonist to signify the main character around whom the story is built. Sometimes it is not so easy to know which is your main character.

Generally speaking, the protagonist is the character whom the reader or audience accompanies for the greater part of the narrative. So usually this character is the one with most screen or page time. Often the protagonist is the character who exhibits the most profound change or transformation by the end of the story.

Furthermore, the protagonist – and in particular what the protagonist learns – embodies the story’s theme.

For simplicity’s sake, let us say for the moment that in ensemble pieces with several main characters, each of them is the protagonist of his or her own story, or rather storyline. Since the protagonist is on the whole a pretty important figure in a story, there is a fair bit to say about this archetype, so this post is going to be quite long.

In it we’ll answer some questions:

- Is the protagonist the most interesting character in the story?

- What are the most important aspects of the protagonist for the author to convey?

- What about the transformation or learning curve?

How Interesting Must The Protagonist Be?

Some say the protagonist should be the most interesting character in the story, and the one whose fate you care about most.

But while that is often the case, it does not necessarily have to be true.

(more…)

Action is character.

So the old storytelling adage. What does that mean, exactly?

In this post, we’ll consider:

- The central or pivotal action – the midpoint

- Actions – what the character does

- Reluctance

- Need

- Character and Archetype

The central or pivotal action – the midpoint

More or less explicitly, the main character of a story is likely to have some sort of task to complete. The task is generally the verb to the noun of the goal – rescue the princess, steal the diamond. The character thinks that by achieving the goal, he or she will get what they want, which is typically a state free of a problem the character is posed at the beginning of the story.

The action is what, specifically, the character does in order to achieve the goal (rescue the princess, steal the diamond). In many cases, this action takes place in a central scene. Central not only in importance, but central in the sense of being in the middle.

Let’s look at some examples. (more…)

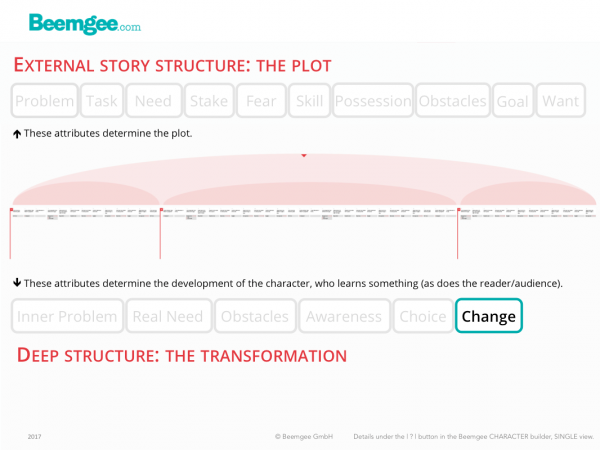

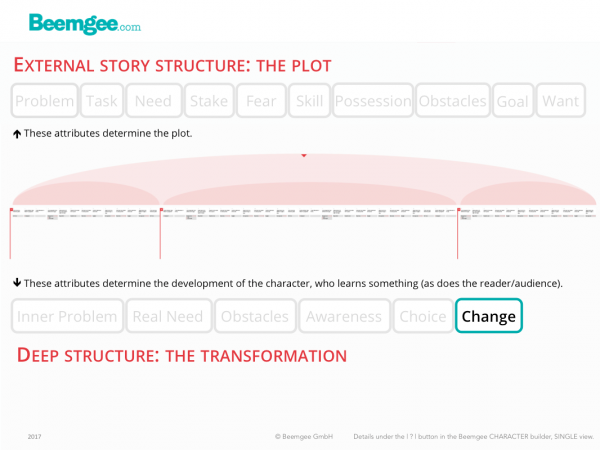

If there is one thing that ALL stories have in common, it is change.

A story, pretty much by definition, describes a change. Indeed, every single scene does.

Within a story, what changes?

At the very least,

- one of the characters, usually the protagonist

- often other characters too

- sometimes the whole story-world

- who understands what – the perception of what is true or valuable

1 – The protagonist changes

We have said before that a protagonist is usually wiser at the end of the story than at the beginning. We have seen that this has something to do with the want, which – whether the character achieves it or not – is usually only attainable by causing a change. Often the change involves the character’s solving the internal problem, so the change takes place within the character. This involves the recognition of the necessity for change, i.e. the acceptance of the real need, and the struggle to achieve it. So all the incidents and events in the plot, the hindrances and obstacles the characters deal with, are in themselves not so very interesting. What interests the audience more is how these events and obstacles change the character.

Having said that, a story may well show no more change than the solving of an external problem. A story world is disturbed, but at the end returns to a similar state. For instance in a detective story, where the crime is solved but the protagonist does not really develop.

2 – Several characters change

Characters don’t change in a vacuum. They learn through interactions with each other. Relationships cause change. In many stories, subplots will tell of the characters that surround the protagonist, and their changes and developments may well cast light on various aspects of the story’s theme. Or perhaps the story is an ensemble piece, where it is not easy (or even necessary) to identify a main protagonist. Or it is a romance, or buddy-story, which apparently has two main characters. Whichever – some level of change usually occurs in all the main characters as a result of how they interact with each other.

There is, by the way, one often neglected archetype who also typically changes. This role is sometimes referred to as foil. We call it the role of the contrastor. The contrastor mirrors and contrasts the protagonist, like Han Solo to Luke Skywalker in Star Wars or the mother to the boy in Boyhood.

3 – The whole world changes

Quite possibly, the entire story-world may be different by the end of the story than it was at the beginning. Story-world as a concept refers to the scope of the world presented in the story, so if the field of action of the characters is small, the story-world is small too. If the story is an epic, the story-world will be big, a version of an entire world.

As an aside on this last point, consider the classical genres. Epics – again, almost by definition – describe a change in a whole world. In a way, so does tragedy, for at the end of the tragedy the world will have lost one or more of its population, since tragedy deals with the change from life to death.

Comedy seeks to describe a different fundamental change in the story-world. The typical structure of comedy, whether we are talking about Aristophanes or modern TV sitcoms, has a stable situation at the beginning which is disturbed by some event or problem. The disturbance causes first a lot of messy but generally non-life-threatening chaos which is resolved by a return to the original undisturbed situation. Even if the main characters end up married, for example, the story-world is brought back to its stable state.

The very serious point of comedy is to demonstrate a fundamental truth: the cyclical nature of change in the universe. Spring always returns, no matter how bleak the winter. Day always comes, no matter how dark the night. Change does not have to be final. Change can be cyclical. Change is life.

4 – The Perception of Truth

The most fundamental change that stories tend to describe is one of recognition of truth. What is not known at the beginning of the story is recognised and thus becomes known at the end. This is obvious in crime stories, but holds true for almost all other stories too. The story therefore amounts to an act of learning. Often the learning curve is observable in the protagonist, who tends to be wiser at the end than at the beginning.

But the point is really that the recipient, the reader or viewer, is actually the one doing the learning – through experiencing the story.

The audience changes.

At least, that’s the general idea. The story provides a physical, emotional and intellectual experience – physical when your heart beats faster or your palms sweat, emotional when you feel for the characters, and perhaps intellectual too if the story gives you pause for thought. If the story achieves none of these responses, then it has failed. An experience, again pretty much by definition, changes you. We learn through experience; so if you have changed, chances are it’s because you have learnt something.

Hence it is not only within the story that a change takes place. It takes place outside of the story as well, in the recipient.

Within some stories one may argue that no real change occurs – Alice does not obviously change due to her experience in Wonderland. But the reader has been taken on a wild journey, and the experience is likely to have left some sort of mark.

How does a story provide an experience?

By allowing the recipient, the audience or reader, to understand and feel change and transformation throughout the story. Every scene describes a change. The entire narrative shows a difference between the “before and after”. Stories have a tendency to symmetry: The beginning of the story makes clear what the state of the protagonist or the story world is before the story journey commences, and the end of the story has a corresponding scene or event that shows what the state is after.

For the author, then, the task is to clearly know the state of things for the protagonist, the cast of characters, the story world, and the audience at the end of the tale, and the state of things at the beginning of the tale. The greater the contrast, the better. Once these two points of reference are known, the author works out the many steps needed to get the protagonist, the cast of characters, the story world, and the audience from one state to the other.

There is a paradox here. The change that occurs is also an expression of new equilibrium. At a very basic level, story structure can be described as follows:

- an external problem (a change in the ordinary world of the protagonist) disturbs the equilibrium of the initial situation

- the disturbance is explored, a struggle ensues in which obstacles must be overcome

- the problem is understood and dealt with, creating a new equilibrium or resolution

So change is all-pervasive in stories, within them in the form of character development, and without in the form of audience understanding. And that is not even to consider the transformational power of telling a story, when the act of telling the story brings about change in the author.

Read here how change is important for every single scene, though we prefer to call them plot events.

Related function in the Beemgee story development tool:

Character Developer

Not developing your story yet? Click here:

Archetypes in stories express patterns.

While plots may be “archetypal” when they exhibit certain forms, in this post we are concerned with character archetypes.

In modern storytelling, to consider them as archetypes might suggest a bit of a corset, perhaps even a straightjacket for the characters. For today’s author, to present a character as an archetype does not seem conducive to achieving psychological verisimilitude.

But an archetype is not the same as a stereotype. An advisor or mentor does not need to be a wise old man like Obi-Wan Kenobi. And an antagonist does not need to be a baddy.

Consider archetypes as powers within a story. Like planets in a solar system, they have gravity and they therefore exert force as they move.

Archetypes denote certain general roles or functions for characters within the system of the story. There is ample room for variation within each role or function. Boundaries between one archetype and another may be fuzzy. And it is possible for one character to stand for more than one archetype.

Archetypes Through The Ages

(more…)

More than any other part of a story, the beginning has to grab the audience’ or reader’s attention.

In the beginning, before audience or readers are emotionally involved and concerned about the fates of the characters, the danger of them turning away from the story is greatest.

Now, there’s more to a beginning than the kick-off event. While being an attention grabber, the entire first section of a story also has to establish the following:

- Who the story is about

- What the story is about

- Where the story takes place

That sounds self-evident, but all the elements needed to answer those three points amount to an awful lot of information. And at this stage, the audience or readers are not yet patient or forgiving, because they are not yet emotionally hooked.

In this post we will:

- look at the who/what/where

- determine the three key events that the first section of a story must include

- provide a checklist of all the elements the first part of a story requires

Who/what/where

(more…)

Stories are about people. Even the ones about robots, or rabbits, or whatever.

If you’re thinking about composing a story, you will probably have some characters in mind that will be performing the action of the story. In stories, action and actors (in the sense of someone who does something) are pretty much the same thing looked at from two differing perspectives, as we have noted in our post Plot vs. Character.

The most obvious difference between characters in stories and people in real life is that story characters tend to be driven. Narratives tend to be more compelling when the characters they describe are highly motivated. Rarely in life are our wants, goals, and perceived needs as clear and powerful as for characters in stories. Our real lives tend to drift rather than head in a specific direction; it is often in retrospect that we ascribe direction when we try to understand our lives by putting them into narratives. Historical personages who seem to demonstrate drive and direction (and have perhaps become historical personages because they had these qualities) make for more interesting biographies than people whose motivations were less strong.

Another aspect that sets characters in fiction apart from people in life is that characters tend to fulfil narrative functions in their story. People, on the other hand, live their lives by acting naturally according to the dictates of their personality. A story is a more or less enclosed unity, while an individual’s life is part of a greater whole. Only in retrospect do we sometimes overlay a narrative onto the biography of an individual – because we tend to feel happier when we perceive structure or direction in the lives of others or indeed our own. We can extract more meaning out of a life that can be told with structure and direction. In fact, there is no way of recounting a person’s biography without making choices concerning structure. If we’re honest, even the choice of which events to relate and how to relate them injects a fair amount of fiction into the story of a life, especially when that life is our own as we tell it to others or ourselves.

Many stories focus primarily on one protagonist. In fiction at least, the protagonist is often wiser at the end of the story than at the beginning. The(more…)

Here at Beemgee, we’re into the thought behind the writing of stories more than the writing itself. So we’re all the more pleased that

Here at Beemgee, we’re into the thought behind the writing of stories more than the writing itself. So we’re all the more pleased that