When the bad guy makes the hero’s journey difficult.

Let’s say your hero or heroine is a falsely accused fugitive from the law. While on the run, every policeman or government agent is effectively an antagonistic obstacle. This is particularly the case if there is a specific character who represents the state and whose mission it is to catch the heroine. This detective or agent casts out the net to catch the fugitive, using all the instruments of the state at his or her disposal in order to actively thwart the heroine’s escape.

Or maybe your story is about a soldier behind enemy lines on a mission to find and destroy (or steal) the enemy’s new super weapon, or perhaps rescue an important person who has been captured. Any enemy soldiers the hero encounters are, of course, obstacles. One could say that they are external obstacles if they just happen to be there, like a patrol unit. But if there is on the enemy side a character who is aware of our hero’s approach and is actively seeking to stop him achieving his mission, then the soldiers and/or henchmen this character sends out to find the hero are not external obstacles but antagonistic obstacles.

As we have said before, this division into three classes of obstacles – internal, external, and antagonistic – is not cut and dried and need not be followed too strictly. But differentiating between the different kinds of obstacles a hero or heroine must face while designing and planning your story can lead to a more exciting plot, simply because you can disperse the obstacles systematically within the story journey and have all the different kinds of obstacle build up to a great crescendo at the climax. (more…)

A story has a beginning, a middle, and an end. How to avoid the ‘saggy middle’.

The middle bit of a story is really the story proper. It is usually the longest section. It comes after the introduction of the main character(s) and the setting up of the context, that is the world of the story, as well as the problems and themes the story deals with.

At the end of the first section – prior to what we’re here calling ‘the middle bit’ –, the protagonist has decided to set off on the story journey. Obviously, this does not have to be physical journey through a particular geography, but it does mean that the main character is somehow entering into new and unfamiliar terrain. In this sense, every story is a ‘fish out of water’ story. The heroine must leave the comfort zone in order for the audience to feel interest in her plight.

Some authors jump right into this unfamiliar territory, showing the run up to it in flashbacks. Anita Brookner’s heroine Edith Hope has already arrived in the Hotel du Lac in the first sentence of the novel. Gradually the reasons for her stay here are revealed as the reader progresses through the novel.

Nonetheless, for an author, it may be advisable to create a marked threshold where the protagonist enters into the alien territory of the middle bit. The exploration and transversal of this territory is what on a plot level the middle bit is about, and it takes up the greater part of the story journey. (more…)

Today’s guest post is by author Stefan Emunds.

Today’s guest post is by author Stefan Emunds.

Stefan’s favorite genre is visionary fiction – stories that have an enlightenment dimension. Enlightenment and storytelling have interesting parallels, which prompted Stefan to write a book about storytelling – The Eight Crafts of Writing.

Get a glimpse of his approach to story craft in his article.

Art and Craft

Storytelling is both art and craft, authoring and writing, plotting and pantsing.

1.1 Art and Authoring

Art is creativity. Creativity requires receptivity to the Muse and its inspirations.

Inspirations arrive as thought-images, which writers put into words. How to turn thought-images into words and assemble those into a structured story with vivid characters and an engrossing world is a matter of craft and skill.

1.2 Craft and Writing

The literal meaning of Kung Fu is a discipline achieved through hard work and persistent practice. Writing is Kung Fu.

Craft gives form to inspirations. Forms limit. Writers love the artistic side of writing, less so crafting, in particular, Story Outline. Writers are prone to procrastinate crafting.

But no limitations, no story. No canvas, no painting. No net, no tennis.

Understanding the difference between freedom and dominion helps to appreciate the constraints of craft. Freedom is a means to an end. We want to be free to do something, for example, to write a book. That’s all there is to freedom. Dominion, on the other hand, is mastery of structure. (more…)

Universal storytelling principles behind the most successful movie series ever.

The sumptuous music of John Barry, the stunning set designs of Ken Adam, the directorial skills of Terence Young or Guy Hamilton, the innovative editing of Peter Hunt, the screen presence of Sean Connery, the zangy theme tune by Monty Norman, memorable actresses, spectacular stunts, and exotic location scouting – a fortunate convergence of individual talents built up the abiding popularity of Ian Fleming’s literary creation, the British MI6 agent James Bond.

Most writers don’t have access to such a talent pool, nor do most authors write action-packed spy capers. Also, 007 stories in particular seem so specific a category that authors might not consider that their own works have much in common with them. So one might be tempted to think that most writers can’t learn anything useful from James Bond.

Many people say there is a James Bond formula. Guy Hamilton, director of four of the early Bond movies, has said not. But there are certainly recurring scene types and structural elements that bear examination. A closer look reveals at least seven dramaturgical principles that any author could consider applying.

- The Kick-off Event

- The Real Reason for M

- The Real Reason for Q

- A Timely Death

- The Antagonist

- Revelation and Confrontation

- Humps

(more…)

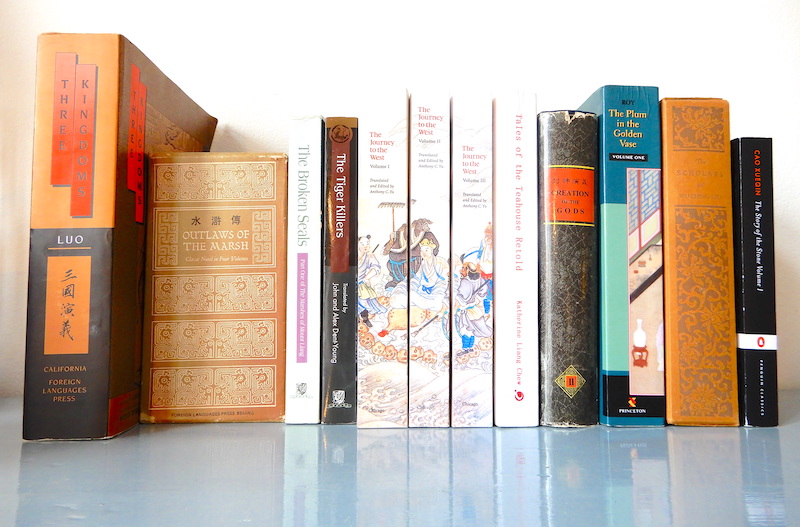

Take a look at your book shelf. Chances are there are European and North American authors there. Perhaps you have some Central or South American writers too. And maybe some Indian or Pakistani novels. And perhaps some Russians.

All of these authors wrote or write in the tradition of European storytelling, via colonial or cultural influence. Modern African authors writing novels, for example, have adopted this written prose text form although African storytelling traditions are primarily oral.

What most of us, at least in the western world, know about how to tell stories is influenced heavily by Aristotle’s Poetics. In this rather thin book, Aristotle describes some basic precepts of dramatic composition that continue to be circulated in creative writing classes and how-to books today.

Another strong influence on western storytelling is the protagonist/antagonist duality which arose along with Christianity. Would there be a Sauron without Satan? A Darth without the Devil? A Voldemort without Lucifer?

So what about stories that were created without any knowledge of Aristotle or Christianity? How are stories that had no contact with the western way of composing narratives different?

Let’s find out by asking … (more…)

Three sorts of opposition, and two things to remember.

Opposition causes conflict

For any character in a story, there may be opponents, not just for the protagonist. So while the protagonist-antagonism struggle may be at the forefront of the story, actually there is a whole system of opposing forces.

Let’s examine how characters in stories work against each other.

- Opposition can come from striving for the same or for opposite ends.

- Opponents can be antagonistic or incidental.

- There are two sorts of opponents, those from without, and those from within.

Same same or different?

An author might take each character at a time and arrange their opponents, which means characters who are either trying to get to the same thing first or whose success in attaining something else would thwart the character’s efforts.

In other words, the opposition (unless it arises by chance, see below) takes the form of either competition or threat. Competition for the same goal: Who will reach the South Pole first? Threat, because the goal of the opponent is opposed to the goal of the other figure: a nature reserve or a hotel complex. Imagine this for yourself using your own example: Your opponents strive for the same goal as you, and if your competitor wins, you get nothing. So your opponents are competing with you for the same goal, for example the same person. Or your opponent wants something completely different from you, and if he achieves that, it means you cannot get what you want. The success of the opponent is therefore a threat to your own well-being.

In either case, the opposition may be … (more…)

Archetypal Antagonism in Documentary Film and Fiction

by Amos Ponger of Mrs Wulf Story Consulting

Stories are intricate mechanisms

Documentary film is a powerful genre that draws much of its energy from the material of real-life action. Consuming documentaries, we as spectators often ignore the fact that documentaries, like fiction, are a constructed clockwork of storytelling. Since the digital revolution, the amounts of raw material for documentary productions have probably grown tenfold, shifting much of the dramaturgical construction work to the editing room. Dealing with hundreds of hours of material you may say that 90 percent of the editing work in documentary film is “finding the story“, discovering what your story is about.

One issue editors often encounter while working on the narratives of documentary films is that many directors tend to neglect the importance of understanding and designing their antagonist or their antagonistic powers, the Antagonism.

Sure, you love your protagonists. You identify with their strivings and journeys, and you as a storyteller have probably given a lot of thought to making them appealing to your audience, giving the audience someone they can identify with. Your protagonists may be an inspiration to you, or you may yourself strongly identify with them, you may share or appreciate some of their characteristics and values.

At the same time you have probably not given your Antagonist/m the same attention. Have you? (more…)

How narrative structure turns a story into an emotional experience.

Image: Comfreak, Pixabay

Storytelling is a bit of an overused buzzword. While we are all – by dint of being human – storytellers, how aware are you of the principles of dramaturgy? What exactly constitutes a story, in comparison to, say, a report or an anecdote?

And just to be clear, the following is not a story. It’s an how-to article.

Whatever the medium – film or text, online or offline –, storytelling has something to do with emotionally engaging an audience, that much seems clear. So is a picture of a cute puppy a story? Hardly.

Stories exist in order to create a difference in their audience. Stories always address problems and tend to convey the benefits of co-operative behaviour.

While there simply is no blueprint to how stories work, let’s examine the elements that recur in stories and try to find some patterns.

Who is the story about?

All stories are about someone. That someone does not have to be a person, it can be an animal (Bambi) or a robot (Wall-e). But a story needs a character. In fact, all stories have more than one character, with virtually no exceptions. This is because the interaction between several characters provides motivation, conflict and action.

Moreover, stories usually have a main character, the figure that the story seems to be principally about – the protagonist. It is not always obvious why one character is the protagonist rather than another. Is she simply the most heroic? Is she the one that develops most? Or does she just have the most scenes?(more…)

Antje Tresp-Welte is the winner of the Your Perfect Plot challenge set by BoD and Beemgee.

In her guest blog post, she gives frank insight into her writing process and her experiences with Beemgee.

Short stories were child’s play

Short stories were child’s play

When something intrigues me, I spin a story out of it. Until a few years ago I wrote mostly fairy tales, short stories for adults, poetry and stories for younger children, some of which were published in magazines. My story about a bad-tempered spectacled snake was published as a little book, “Charlotte and the Blue Lurker”. For all these stories I only sketched a few thoughts as planning and then wrote them down relatively quickly.

By now, book projects fascinate me too. Currently they are crime novels and fantasy for children from 8 or 10 years.

Long takes longer …

During a holiday at the North Sea I had the idea for my first crime novel. In it, the protagonist, an eleven-year-old very imaginative boy with a penchant for drawing, not only saves his grandma’s tea room from demolition, but is also involved in a mysterious story about a pirate who died long ago. I developed the original idea into a plot at a seminar for authors. I found the topic so great that I couldn’t wait to start writing it. Beforehand, I made notes on the individual characters and considered important cornerstones of the plot with the help of the hero’s journey. I started off with a great momentum and was soon able to read the first chapters to my son. Unfortunately his comment was, “Mama, that is much too long!”

… not to be longwinded

My two test readers came to a similar conclusion and I too had noticed that it somehow “grated”. I wasn’t really getting to the point. Was it due to my preliminary planning? Was it not detailed enough? I dived into the text, shortened passages, removed individual characters and worked out others more precisely. This changed entire storylines. At the same time my story gained more (narrative) speed and I found the tone for the language. (more…)

The logline is probably the hardest sentence to write.

The logline sums up a story in one sentence. This sentence should be memorable and clear, which means it is unlikely to be much longer than thirty words or to have complex syntax.

Once your reader has read your logline – or your listener heard it –, they will ideally know the following about your story:

- who it is about

- what the central conflict or main problem is

- what the most important characters do in the story

- why they do it, i.e. what their motivations are

- how they do it

- where all this happens, i.e. what the setting is

- when it happens, i.e. what the period is

The first of these points even counts double – since usually the logline should convey not only who the main protagonist is, but also what antagonism she faces.

What’s the logline for?

The purpose of the logline is to pitch your story.(more…)

The protagonist is the main character or hero of the story.

Photo by Jack Moreh on Freerange

But “hero” is a word with adventurous connotations, so we’ll stick to the term protagonist to signify the main character around whom the story is built. Sometimes it is not so easy to know which is your main character.

Generally speaking, the protagonist is the character whom the reader or audience accompanies for the greater part of the narrative. So usually this character is the one with most screen or page time. Often the protagonist is the character who exhibits the most profound change or transformation by the end of the story.

Furthermore, the protagonist – and in particular what the protagonist learns – embodies the story’s theme.

For simplicity’s sake, let us say for the moment that in ensemble pieces with several main characters, each of them is the protagonist of his or her own story, or rather storyline. Since the protagonist is on the whole a pretty important figure in a story, there is a fair bit to say about this archetype, so this post is going to be quite long.

In it we’ll answer some questions:

- Is the protagonist the most interesting character in the story?

- What are the most important aspects of the protagonist for the author to convey?

- What about the transformation or learning curve?

How Interesting Must The Protagonist Be?

Some say the protagonist should be the most interesting character in the story, and the one whose fate you care about most.

But while that is often the case, it does not necessarily have to be true.

(more…)

Archetypes in stories express patterns.

While plots may be “archetypal” when they exhibit certain forms, in this post we are concerned with character archetypes.

In modern storytelling, to consider them as archetypes might suggest a bit of a corset, perhaps even a straightjacket for the characters. For today’s author, to present a character as an archetype does not seem conducive to achieving psychological verisimilitude.

But an archetype is not the same as a stereotype. An advisor or mentor does not need to be a wise old man like Obi-Wan Kenobi. And an antagonist does not need to be a baddy.

Consider archetypes as powers within a story. Like planets in a solar system, they have gravity and they therefore exert force as they move.

Archetypes denote certain general roles or functions for characters within the system of the story. There is ample room for variation within each role or function. Boundaries between one archetype and another may be fuzzy. And it is possible for one character to stand for more than one archetype.

Archetypes Through The Ages

(more…)

Stories are about people. Even the ones about robots, or rabbits, or whatever.

If you’re thinking about composing a story, you will probably have some characters in mind that will be performing the action of the story. In stories, action and actors (in the sense of someone who does something) are pretty much the same thing looked at from two differing perspectives, as we have noted in our post Plot vs. Character.

The most obvious difference between characters in stories and people in real life is that story characters tend to be driven. Narratives tend to be more compelling when the characters they describe are highly motivated. Rarely in life are our wants, goals, and perceived needs as clear and powerful as for characters in stories. Our real lives tend to drift rather than head in a specific direction; it is often in retrospect that we ascribe direction when we try to understand our lives by putting them into narratives. Historical personages who seem to demonstrate drive and direction (and have perhaps become historical personages because they had these qualities) make for more interesting biographies than people whose motivations were less strong.

Another aspect that sets characters in fiction apart from people in life is that characters tend to fulfil narrative functions in their story. People, on the other hand, live their lives by acting naturally according to the dictates of their personality. A story is a more or less enclosed unity, while an individual’s life is part of a greater whole. Only in retrospect do we sometimes overlay a narrative onto the biography of an individual – because we tend to feel happier when we perceive structure or direction in the lives of others or indeed our own. We can extract more meaning out of a life that can be told with structure and direction. In fact, there is no way of recounting a person’s biography without making choices concerning structure. If we’re honest, even the choice of which events to relate and how to relate them injects a fair amount of fiction into the story of a life, especially when that life is our own as we tell it to others or ourselves.

Many stories focus primarily on one protagonist. In fiction at least, the protagonist is often wiser at the end of the story than at the beginning. The(more…)