How perceptive a character is of her surroundings may have dramaturgical relevance.

A character who is good at noticing small details may make a good spy or detective, so if you are developing a detective or spy you may want to give your character this ability. But whatever your character’s profession, stop at least once per scene and ask yourself,

What is a detail that only this character might notice?

Why is this important? Because their perceptions can make characters more interesting and vivid.

If a certain plot event hinges on a character perceiving some small detail or other, it may be a good idea to plant a foreshadowing moment long before the scene, to heighten the impact of the act of perception.

Furthermore, a character’s perception may influence how your audience understands and enjoys the entire story. How exactly depends on two important factors:

- narrator

- point of view

(more…)

How narrative structure turns a story into an emotional experience.

Image: Comfreak, Pixabay

Storytelling is a bit of an overused buzzword. While we are all – by dint of being human – storytellers, how aware are you of the principles of dramaturgy? What exactly constitutes a story, in comparison to, say, a report or an anecdote?

And just to be clear, the following is not a story. It’s an how-to article.

Whatever the medium – film or text, online or offline –, storytelling has something to do with emotionally engaging an audience, that much seems clear. So is a picture of a cute puppy a story? Hardly.

Stories exist in order to create a difference in their audience. Stories always address problems and tend to convey the benefits of co-operative behaviour.

While there simply is no blueprint to how stories work, let’s examine the elements that recur in stories and try to find some patterns.

Who is the story about?

All stories are about someone. That someone does not have to be a person, it can be an animal (Bambi) or a robot (Wall-e). But a story needs a character. In fact, all stories have more than one character, with virtually no exceptions. This is because the interaction between several characters provides motivation, conflict and action.

Moreover, stories usually have a main character, the figure that the story seems to be principally about – the protagonist. It is not always obvious why one character is the protagonist rather than another. Is she simply the most heroic? Is she the one that develops most? Or does she just have the most scenes?(more…)

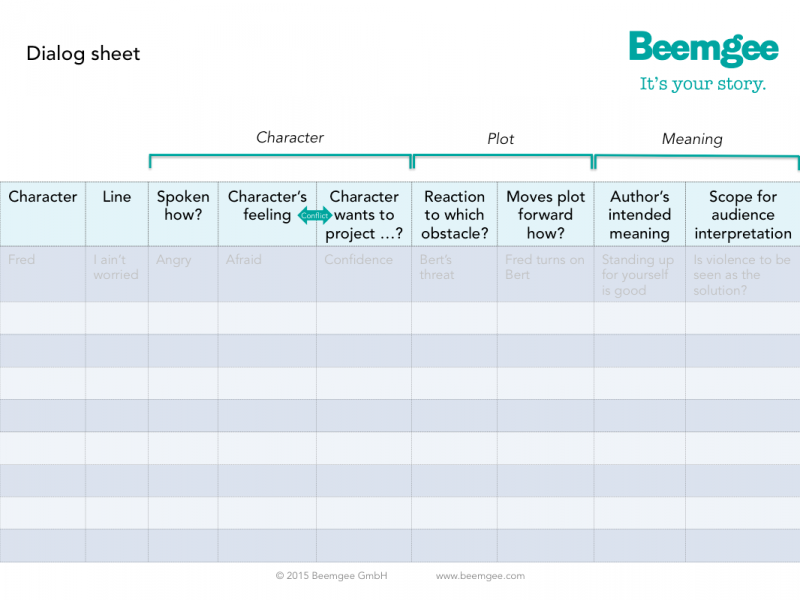

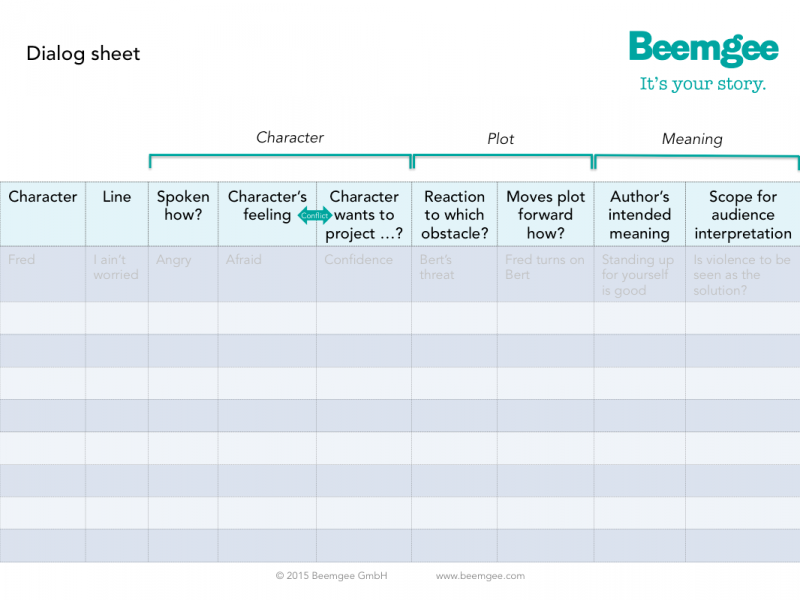

The seven elements of every line of dialog in a story.

Dialog enlivens stories. But dialog in stories is very different from real spoken language. It conveys information that the audience needs to know in order to understand the story as well as the characters – the one speaking the lines as well as the one reacting to them.

There is the rule of thumb that it’s better for the author to use action to explain things or move the plot forward than dialog, at least in film. Certainly, when the author makes characters say things solely to convey some bit of knowledge to the audience or reader, the lines tend to feel false. That’s a form of exposition, explanatory stuffing. If in doubt, leave it out. You’ll be surprised how much the audience understands even without explanations.

On the other hand, Elmore Leonard noted how readers don’t usually skip dialog. People like dialog. Dialog can be exciting. Dialog can be action. So authors had better know how to write it.

Here are seven things you ought to consider about every single line of dialog you put into your characters’ mouths. We’ve created this free table to help you. Feel free to download, use and share it.

1

If you’re writing(more…)

In stories, the characters’ emotions are ultimately the sources of their actions, because motivations are ultimately based on emotions.

Determining the emotional core of a character in a story may lead to a clearer understanding of that character’s behaviour, i.e. their actions.

What we’re getting at here is essentially a premise for creating a story. We have noted that if you plonk a group of contrasting characters in a room – or story-world –, then a plot can emerge out of the arising conflicts of interest. If you’re designing a story, one approach is to create the contrasts between the characters (their essential differences of character) by giving each character a core trait or emotion. One character may be frivolous, another penny-pinching. One may be fearful, another cheeky.

You might object: Isn’t that a bit one-dimensional? Aren’t characters with just one core emotion flat?

Not necessarily. Focusing on one core emotion is not a cheap trick. It is as old as storytelling.

Classical Storytelling

Ancient(more…)

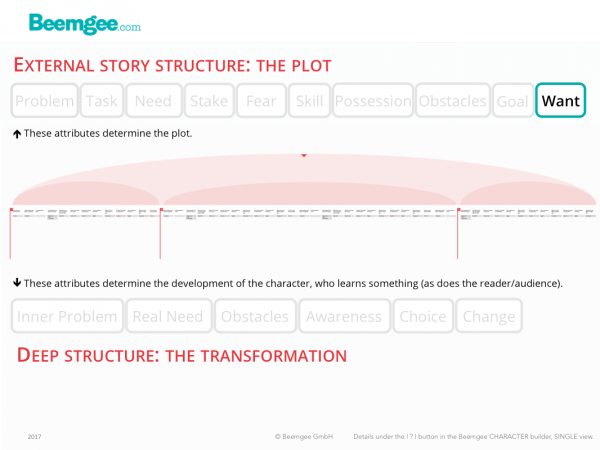

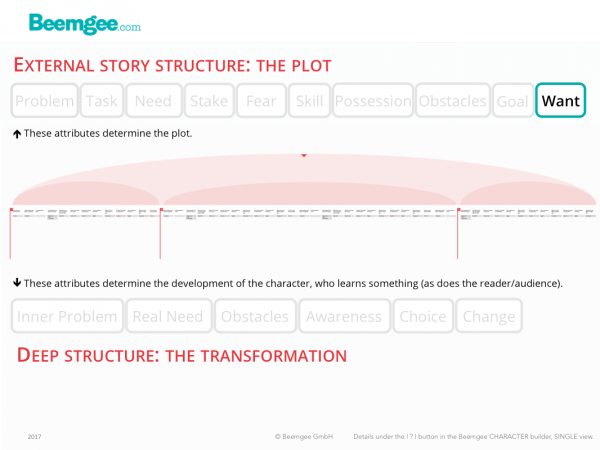

Stories are about people who want something.

We can distinguish between two different types of want:

- the wish, or character want

- the plot want

Marty McFly wishes to be a musician (character want). He also wants to get Back to the Future (plot want).

The wish or character want is a device which adds cohesion to the story, usually in the form of the set-up/pay-off. Marty is seen at the beginning of the film practicing the guitar; at the end of the film he plays at a concert. A character-inherent wish is a useful technique to make the character clearer to the audience, but it is not essential to composing a story.

Indispensable is what we have called the plot want. As a result of the external problem – the trigger event that sparks the chain of cause and effect which the bulk of the plot consists of –, the character feels an urge, which provides the motivation for the character’s actions in the story.

The want is the state for which the character strives, and is distinct from the goal.

In this post we’ll be talking about active vs. passive characters, motivation, the difference between a want and a goal, a couple of writer traps to avoid, and contradictory wants.

Active Characters

Characters have to be actively acting of their own volition. The want has to be urgent and strong enough for them to do things. If the want is missing or too weak, the character will lack motivation and appear passive. A passive character is usually not interesting enough to hold the audience’ or readers’ attention.

Why is this so?

Evolutionary explanations of stories attempt to shed light on the phenomenon. When characters react to events rather than cause them, they appear weak, as victims in a chaotic, uncontrolled world. Which means that there is not much we can learn from them. Humans try to see cause and effect in everything, not just in stories. And humans experience stories physically and emotionally (our hearts beat faster, our palms sweat), so there is really not much difference between how we experience a story and real life. Since we learn from experience, we instinctively prefer stories which provide us with experiences that benefit us in some way. In stories we vicariously experience or practice primarily social problem-solving, without suffering real-life consequences. We tend to learn more when we experience stories of self-motivated problem-solving.

Motivation

There is a good reason for that cliché about actors always asking about their motivation. It is motivation that prompts the characters in a story to do the things they do. Stories seem to work best not only when characters are active rather than passive, but often when they have comprehensible reasons for their activity.

The reason for what a character wants is usually comprehensible for the audience or reader because of the external problem. In simple terms, the character wants to solve the problem. Take the Cinderella story as an example. Her problem is that she is bound to the stepmother and her two nasty daughters.

In other words, the want is a vision the character has of his or her situation without the problem. Hence what the character wants is actually a particular state of being. Such a state might mean being in a position of wealth, power or respect, or being in a happily ever after relationship. Cinderella wants merely to be free of her involuntary servitude, if only for a little while.

This makes the want distinct from the goal, which is the specific gateway to the wanted state of being, as perceived by the character. A story usually sets up a goal the character needs to reach or attain in order to achieve the want. In Cinderella’s case, it is attending the ball.

So, a story has its characters pursue their wants. These different wants oppose each other, causing conflicts of interest. The conflicting wants make the characters active, and the audience/readers like stories about actions, that is, about characters who do things.

Sounds simple.

And yet frequently stories seem to mess up on this vital point.

Next to passive characters without a strong enough want, lack of clear motivation is a huge writer trap. It is possible to write a whole story full of characters who are reactive instead of active, or who do things of their own volition but without that volition being clearly recognisable to the audience/reader. It is perhaps even tempting to write stories like that, because they seem more lifelike. In real life, people do not necessarily have distinct goals. Often, our wants are vague and not clearly definable. What about writing a realistic story about a character with a general sense of dissatisfaction, who, like so many of us, has lost sight of any clear objective in life?

It’s doable, certainly. But the audience/readers will probably start to look for the specific want of such a character. They would probably begin to expect the story to be about this character’s search for a clear objective in life. That might be the want the audience would tacitly ascribe to the character.

And if the story does not bear such motivation out, the risk is significant. Because stories in which the audience does not understand what the characters want lack emotional impact.

Contradictory Wants

A way of adding psychological depth and emotional complexity to characters is to give them several and even contradictory wants. Gollum in Lord Of The Rings wants the ring. Yet a part of him also wants to give up the ring and help Frodo. Next to solving the case, Marty Hart in True Detective wants to be a good husband and family man, but he also wants affairs with other women. That’s three wants for one character.

A want is not merely a yearning, it is an expression of values. What a character desires shows the audience something about that character. In this sense, two contradictory wants provide the basis for a powerful scene of choice. At a crisis point, the character may face a dilemma and have to choose between two courses. Both might lead to some state the character desires, but these desires prove to be mutually exclusive. For the audience, which choice is the right one might be obvious – they will be rooting for the character to go one way. But for the character there may be a strong pull the other way. The final choice shows the character’s moral fibre – and often expresses the story’s theme.

When not to want

Is it really always absolutely necessary for every character to have a clearly defined want?

Not entirely. Because, of course, there are exceptions.

In certain cases, the author might deliberately obfuscate the why of a character’s actions in order to inject mystery. Not knowing something keeps the audience/reader guessing and turning the pages or not switching the channel. Usually this mystery is cleared up at some point. The audience tends to expect that. Which implies that even if the want was not made clear to the audience early in the story, it was there in the character nonetheless – and certainly the author was aware of it.

Injecting mystery by keeping character motivations hidden is not in itself a writer trap. But nearly. When tempted to use such a device, an author should at least consider if it would not actually be more interesting for the audience to know the character’s motivation.

Having said that, there are rare cases where a character’s motivation does remain unexplained. And those cases can be powerful. Especially when it’s a baddy we don’t understand.

Think of Iago in Shakespeare’s Othello, who is simply bad to the bone and we’ll never really know why. Shakespeare – deliberately, one presumes – gives no hint as to what Iago hopes to achieve by ruining Othello. Shakespeare might easily have given Iago some clearly understandable motivation, such as revenge of a past wrong, envy of Othello’s success, desire to usurp Othello’s position, lust for Desdemona. But he didn’t. And Iago is one of the most superb villains ever.

Another possible exception are (fiction) memoirs in the first person, such as David Copperfield, The Catcher in the Rye, Saul Bellow’s The Adventures of Augie March, or William Boyd’s Any Human Heart. In such stories, the effect of the narrator telling his or her own story creates a disparity between the time of the story told and the implicit future time of the act of telling. The narrator is relating a past from the perspective of an older self. This older self has reached a state of being which is different from that of the character being told about – the narrator is wiser than his or her younger self. This creates an effect for the reader: the reader wants to know how the character reach this older, wiser state. With this device, it is possible to make character wants less obvious or direct and still maintain an emotional drive to the story.

Perhaps the most interesting thing about a character’s want is how it stands in conflict with what that character really needs.

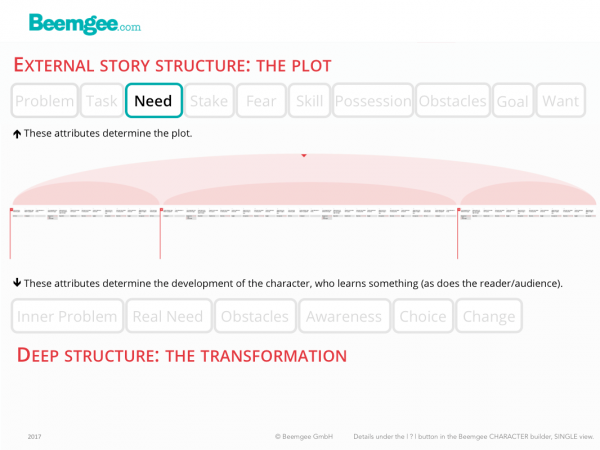

Related function in the Beemgee story development tool:

Character Developer

Click to open a new story project:

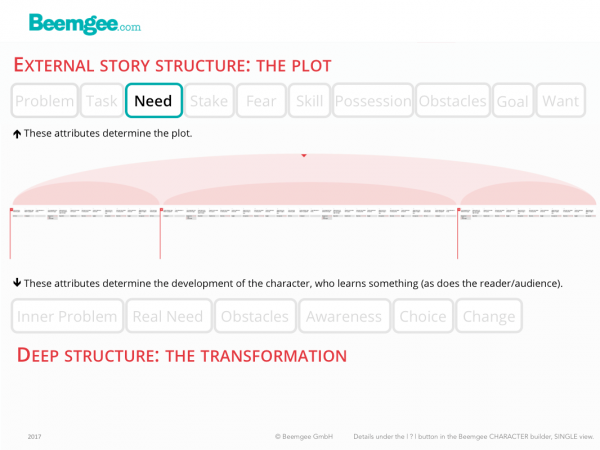

A character with a goal needs to do something in order to reach it.

The outward needs of a character – things she needs to acquire or achieve in order to reach the goal – divide the story journey into stages.

In storytelling, characters usually know they have a problem and there is usually something they want. They tend to set themselves a goal which they believe will solve their problem and get them what they want.

In order to get to the goal, the character will need something. Some examples: If the goal is a place, a means of transportation is necessary to get there. If we can’t rob the bank alone, we’ll have to persuade some allies to join our heist. If the goal is defeating a dragon, then some weapons would be helpful. If magic is needed, we’ll have to visit the magician to pick some up.

While the perceived need might be an object or a person, it usually requires an action. We’ll need a car, so do we buy one or steal one? We’ll need a sword, so do we pull one out of a stone or go to the blacksmith? If we need help, who do we ask and how do we talk them into joining us? We’ll need magic, but how do we find a magician? Ask an elf or go to the oracle for advice?

So, once the goal is set, a vision of the way to reach it opens up to the protagonist – and with that to the audience/reader. At the very least, the first step of the way presents itself. All this is what the character is conscious of.

In other words, the character forms a plan.

The plan is communicated more or less explicitly to the audience. The anticipation of how things will not go quite according to plan is part of the pleasure. There must always be surprises in store for the characters as well as for the audience.

Stages and Obstacles

The perceived needs are (more…)

We humans have a built-in predisposition to expect agency.

We look for the person or thing responsible for any action or phenomena we experience; we seek to ascribe “agency” to what we perceive. What this means is that when we notice that something happened, we tend to look for the cause of the event. This probably has a simple evolutionary explanation. If we hear a rustle in the bush behind us, we immediately turn around to see what moved. This reflex is a safety mechanism to detect threats. Before homo sapiens lived in houses, the individuals for whom this reflex worked most efficiently probably lived longer, and thus had better chances of passing on their genes. The point is, we assume that something or someone caused the phenomenon (the rustle) and seek to attribute it to an agent. If we are sitting in our living room and hear a floorboard creak in the hall, we would want to know what caused it too.

This safety mechanism has all sorts of ramifications. It influences(more…)