How perceptive a character is of her surroundings may have dramaturgical relevance.

A character who is good at noticing small details may make a good spy or detective, so if you are developing a detective or spy you may want to give your character this ability. But whatever your character’s profession, stop at least once per scene and ask yourself,

What is a detail that only this character might notice?

Why is this important? Because their perceptions can make characters more interesting and vivid.

If a certain plot event hinges on a character perceiving some small detail or other, it may be a good idea to plant a foreshadowing moment long before the scene, to heighten the impact of the act of perception.

Furthermore, a character’s perception may influence how your audience understands and enjoys the entire story. How exactly depends on two important factors:

- narrator

- point of view

(more…)

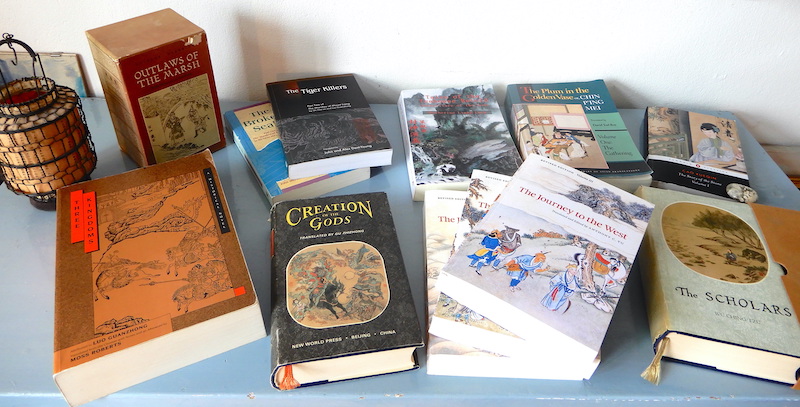

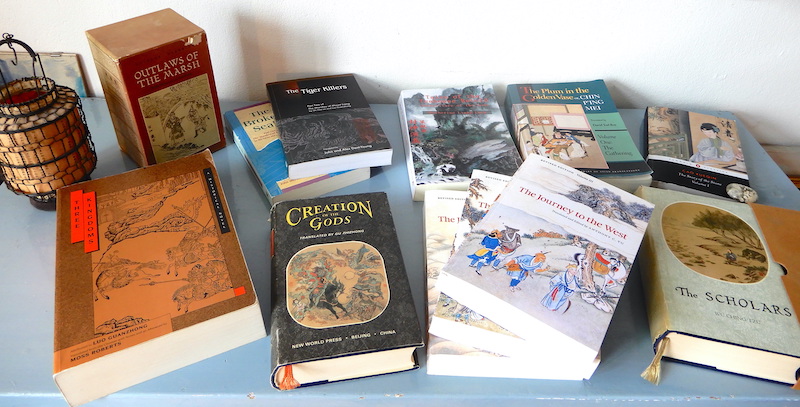

You have likely heard of The Divine Comedy, of Don Quixote, of Shakespeare – but have you heard of the Three Kingdoms? Of Sun Wukong? Of Cao Xueqin?

We asked ourselves, how are stories that had no contact with the western way of composing narratives different? Are the principles of storytelling really universal across cultures? Our idea was to find out by taking a look at classical Chinese literature. We discovered a number of interesting aspects to the Chinese way of telling stories, and have summarised them here.

In this post, we’ll tell you about the novels we read. Each was a revelation in its own way. The long-form novel came along quite suddenly in China just over 500 years ago. Generally recognised as the first great Chinese novel is Three Kingdoms, which appeared around 1494 CE. The most modern of the novels we’re considering here was published around 1760. That means we’re looking at Ming and Qing dynasty literature.

So which classical Chinese novels should you read? Here’s our list of favourites.

Our Top 7 Classical Chinese Novels

Nr 1

(more…)

One of the most far-reaching decisions an author must make is how to narrate the story. Or: Who is telling the story to whom under which circumstances?

To be fair, this question is a relatively new one for authors to ponder. In the pre-modern age, authors just grabbed their quills and started writing. But as novels became more sophisticated, technical questions became more explicit and relevant. Narrative voice – the matter of who is talking here, or what is this text we’re reading purporting to be – is a factor at the latest since James Joyce’ Ulysses and all the self-aware post-modern novels that followed. Previously, there had already been a difference between author and narrator. When in a novel by Charles Dickens you, dear reader, are directly addressed, then already there is some sort of discrepancy between the person saying “dear reader” to you and Charley Dickens the man. But this discrepancy didn’t become a popular topic to construct stories around until the twentieth century.

Anyway, while not a traditional archetype, and in many cases not even a participating character, the narrator is never really quite the same entity as the author either.

To begin with the basics, the standard narrator types are:

- first-person, where usually the protagonist tells his or her own story

- third-person limited, where a narrator tells a story from one character’s point of view only, meaning that the audience/reader is not told of any events that this character is unaware of

- third-person omniscient, where the narrator can relate what any of the characters are doing and thinking, and is not limited in what to present to the audience/reader

In film, first person and third-person limited effectively amount to the same thing: the audience gets one person’s perspective on the story per shot or scene (there is also the first-person “point of view” camera angle, but rarely is an entire film presented that way). In prose, first and third person is the difference between “I did this” and “she (or he) did that”. This is a stylistic choice. In the sense of what the narrator knows and tells, there is not necessarily much difference.

Close or Distant

But potentially there is big difference between narrative stance. A narrator who is limited to reporting in third person on only one character can do so “close” or “from a distance”.(more…)