Making Facts Memorable: Structuring Non-Fiction

The Two Types of Non-Fiction Book.

Here at Beemgee, we know a lot about how stories work. We consider ourselves experts on dramaturgy and narrative. Fiction is our forte.

But we don’t claim to understand non-fiction anywhere near as well. That’s why we were very keen to attend a session on non-fiction by Yvonne Kraus at the author conference at this year’s Leipzig book fair.

Here’s a brief summary of what she taught us.

The Two Basic Structures of Non-Fiction Books

1. Reference and articles

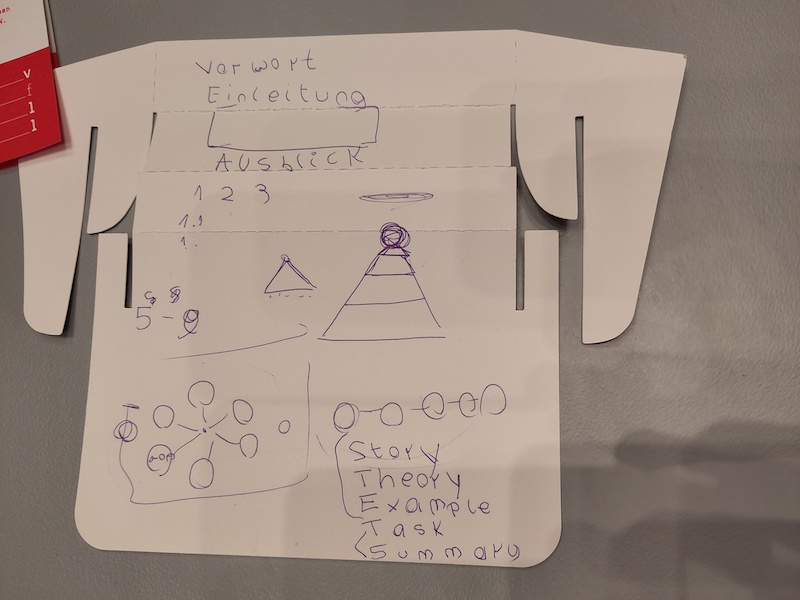

Look at the bottom left of the scribble in the photo and you’ll see circles arranged in a circle, with lines going from the individual circles into the center of the arrangement. Each individual circle stands for a unit of content, or a chapter. This representation is trying to express a way of reading a book. The reader can dip into any chapter at will, they each function independently of each other, it is not necessary to read them in sequence or to read all of them. Cookbooks are a good example. Each recipe constitutes a chapter, a unit, and can be consulted without knowing the other units.

If we are talking about content more complex than recipes, for example political articles, the units may contain information that is repetitious in the book as a whole if this information is necessary in order to understand the content of several individual chapters. I.e. it may well be the case that the same basic facts are stated in several of the chapters if they are requisite to know, because the author cannot assume that the reader will have read previous chapters in the book already. The chapters do not build on each other. Certain units of information may be referenced, for example a lasagne recipe may call for béchamel sauce, the making of which may not be described in the lasagne recipe but instead the lasagne recipe may simply say, “see the recipe for béchamel sauce on page 27 in the section ‘basic sauces'”.

The main body of the book may be subdivided into meaningful sections. The promise the book makes to the reader is that the reader will find specific information on a particular subtopic easily, and without having to read the entire book.

Furthermore, there may well be at least two units or chapters that stand apart, arranged “around” or “before and after” the main bulk of the book:

- an introductory section or prolog which explains, among other things, how to read the book

- a closing outro or epilog which might contain a summary or conclusion

2. Step by step from beginning to end

Look at the bottom right of the scribble in the photo and you’ll see circles arranged in a line. Again, each circle represents a unit of content and meaning, or a chapter. In this case, the author assumes the reader will read the book from beginning to end, so information will be structured in such a way as to be received by the reader starting on the first page and continuing on all the way through to the final page. The process described will be more long-term in comparison to the reference structure – compare instructions for building a complicated machine (or a Lego set) to recipes in a cook book. In a step by step guide or an indepth study, the reader is being informed on the topic concerned from A to Z. It may be necessary to know the contents of chapter one in order to fully understand chapter two, and so on.

It can be more difficult for the author to judge how much information she needs to supply to the readers at any point; that said, there will always be a degree of assumed knowledge in the readership or target group of the book. While the knowledge of the readers grows from chapter to chapter, repetitions are a service from the author to the reader, because one cannot expect the reader to remember every single detail transmitted in previous pages.

The promise of such abeginning to end book is essentially a transformation; having read this book you will be more knowledgeable about its topic than beforehand. You will understand something you previously were unaware of. This means that the book has an argument, a case, an agenda. It wants to achieve something: a change in its readers. In order to do this, it will arrange the argumentation in a convincing way, providing more and more backing for its case.

Such step by step non-fiction books may also have an introduction and a conclusion, or a foreword and afterword. The epilog will point out how far the reader has come since the prolog, because the book has taken its readers on a journey of revelation – which is actually what fiction does too.

What both non-fiction approaches have in common

In both types of non-fiction book, the contents page(s) should be as clear as possible. Before buying a non-fiction book, most people will glance at the contents page to reassure themselves that the book actually contains what they want and expect it to, what the cover and blurb promise. Put the contents page at the front because certain internet book shop platforms offer a look inside the book which usually contains the first few pages and not necessarily the last.

If you divide your book into sections, each section title should be named so that its content is readily apparent. If there are subsections to the sections, try to keep the system of organisation clear and the levels distinct. Usually, more than two levels of subsection is not a good idea. As a rule of thumb, the number of chapters within a section or subsection should be between five and nine.

A foreword explains the why of the book, the reason you wrote it, the story behind why you felt compelled or were chosen to write the text that follows, and what makes you qualified. Many readers skip the foreword, so don’t place essential information here.

An introduction elucidates the structure of the book – whether it is to dip into or read from start to finish, as well as other specifics of arrangement or layout that the book may contain. The introduction defines the important recurring terms, to make sure that readers are really on the same page as you, the author. The introduction explains in what topic or field the book can help and how the book works, in what way it seeks to achieve its aim. The introduction provides expectation management. It supplies the promise, and may tease at the transformation that is to come.

In almost all non-fiction, clarity wins over beauty. Keep the text as simple as you can in order to ensure that readers will understand what you are trying to say. Unlike fiction, which often tries to lead readers astray or mystify or obfuscate what is actually going on until a moment of revelation, non-fiction tries to make readers understand at every stage. That the readers receive, process, and gain awareness through the information your book provides is probably more important than beauty of prose. Having said that, clear language is, of course, beautiful, and carefully worded prose is, of course, easier and more fun to read than shoddily written text.

The title of your book should preferably be memorable and enticing. It points to what the book is about, obviously, but may do so indirectly when it is accompanied by a pithy subtitle that makes the meaning of the title absolutely clear.

An Invitation

Consider your non-fiction book as an invitation. There are things the invitee expects and ought to receive.

This is the order:

- Topic or theme

- For whom is this book relevant?

- The elevator pitch – what this book is about, explained in just a few seconds, or two sentences at most.

- Foreword

- Introduction

- The bulk of the book – the chapters organised in one of the two ways outlined above.

- Outro or summary

- Final brief part, the delivery of the promise and more, the icing on the cake, the outlook into the future, and a pointing to what to do with the newly recognised transformation, what comes next after this revelation.

STETS

Finally, whether reference dipping in or argumentative step by step non-fiction, each chapter, possibly including parts such as the foreword or epilog, may be constructed in the following pattern:

S for Story – begin each chapter with an anecdote, because people relate to stories more than to factual reports

T for Theory – explain your point with the theory and the facts

E for Example – back up your point and make the theory clear with examples

T for Task – activate the readers, ask questions, perhaps even give them something to do which will help them understand the theory and experience an example themselves, rather than just read about it

S for Summary – repeat in few words what the reader has learned in this chapter

Now that we know how non-fiction works, we feel inspired to try it out ourselves. We may just write a book on

- Topic or theme: Dramaturgy and how to structure fiction

- Relevant for: Authors and storytellers, for page, stage or screen

- The elevator pitch:

The Beemgee handbook on the craft of developing stories focuses on the emotional responses of the audience and explains in depth and detail each aspect of dramaturgy, helping authors to outline compelling plots and develop engaging characters. - Foreword …

- Introduction …

- The bulk of the book – the chapters organised in one of the two ways outlined above.

- Outro or summary …

- Final brief part, the delivery of the promise and more, the icing on the cake, the outlook into the future, and a pointing to what to do with the newly recognised transformation, what comes next after this revelation. …

Try Beemgee for your non-fiction project: