The Importance of Change in Stories

If there is one thing that ALL stories have in common, it is change.

A story, pretty much by definition, describes a change. Indeed, every single scene does.

Within a story, what changes?

At the very least,

- one of the characters, usually the protagonist

- often other characters too

- sometimes the whole story-world

- who understands what – the perception of what is true or valuable

1 – The protagonist changes

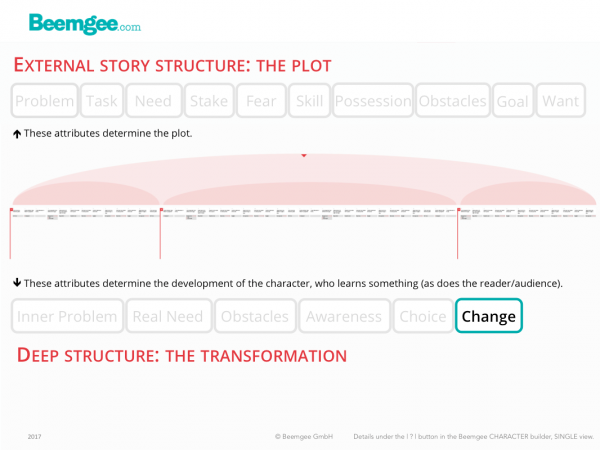

We have said before that a protagonist is usually wiser at the end of the story than at the beginning. We have seen that this has something to do with the want, which – whether the character achieves it or not – is usually only attainable by causing a change. Often the change involves the character’s solving the internal problem, so the change takes place within the character. This involves the recognition of the necessity for change, i.e. the acceptance of the real need, and the struggle to achieve it. So all the incidents and events in the plot, the hindrances and obstacles the characters deal with, are in themselves not so very interesting. What interests the audience more is how these events and obstacles change the character.

Having said that, a story may well show no more change than the solving of an external problem. A story world is disturbed, but at the end returns to a similar state. For instance in a detective story, where the crime is solved but the protagonist does not really develop.

2 – Several characters change

Characters don’t change in a vacuum. They learn through interactions with each other. Relationships cause change. In many stories, subplots will tell of the characters that surround the protagonist, and their changes and developments may well cast light on various aspects of the story’s theme. Or perhaps the story is an ensemble piece, where it is not easy (or even necessary) to identify a main protagonist. Or it is a romance, or buddy-story, which apparently has two main characters. Whichever – some level of change usually occurs in all the main characters as a result of how they interact with each other.

There is, by the way, one often neglected archetype who also typically changes. This role is sometimes referred to as foil. We call it the role of the contrastor. The contrastor mirrors and contrasts the protagonist, like Han Solo to Luke Skywalker in Star Wars or the mother to the boy in Boyhood.

3 – The whole world changes

Quite possibly, the entire story-world may be different by the end of the story than it was at the beginning. Story-world as a concept refers to the scope of the world presented in the story, so if the field of action of the characters is small, the story-world is small too. If the story is an epic, the story-world will be big, a version of an entire world.

As an aside on this last point, consider the classical genres. Epics – again, almost by definition – describe a change in a whole world. In a way, so does tragedy, for at the end of the tragedy the world will have lost one or more of its population, since tragedy deals with the change from life to death.

Comedy seeks to describe a different fundamental change in the story-world. The typical structure of comedy, whether we are talking about Aristophanes or modern TV sitcoms, has a stable situation at the beginning which is disturbed by some event or problem. The disturbance causes first a lot of messy but generally non-life-threatening chaos which is resolved by a return to the original undisturbed situation. Even if the main characters end up married, for example, the story-world is brought back to its stable state.

The very serious point of comedy is to demonstrate a fundamental truth: the cyclical nature of change in the universe. Spring always returns, no matter how bleak the winter. Day always comes, no matter how dark the night. Change does not have to be final. Change can be cyclical. Change is life.

4 – The Perception of Truth

The most fundamental change that stories tend to describe is one of recognition of truth. What is not known at the beginning of the story is recognised and thus becomes known at the end. This is obvious in crime stories, but holds true for almost all other stories too. The story therefore amounts to an act of learning. Often the learning curve is observable in the protagonist, who tends to be wiser at the end than at the beginning.

But the point is really that the recipient, the reader or viewer, is actually the one doing the learning – through experiencing the story.

The audience changes.

At least, that’s the general idea. The story provides a physical, emotional and intellectual experience – physical when your heart beats faster or your palms sweat, emotional when you feel for the characters, and perhaps intellectual too if the story gives you pause for thought. If the story achieves none of these responses, then it has failed. An experience, again pretty much by definition, changes you. We learn through experience; so if you have changed, chances are it’s because you have learnt something.

Hence it is not only within the story that a change takes place. It takes place outside of the story as well, in the recipient.

Within some stories one may argue that no real change occurs – Alice does not obviously change due to her experience in Wonderland. But the reader has been taken on a wild journey, and the experience is likely to have left some sort of mark.

How does a story provide an experience?

By allowing the recipient, the audience or reader, to understand and feel change and transformation throughout the story. Every scene describes a change. The entire narrative shows a difference between the “before and after”. Stories have a tendency to symmetry: The beginning of the story makes clear what the state of the protagonist or the story world is before the story journey commences, and the end of the story has a corresponding scene or event that shows what the state is after.

For the author, then, the task is to clearly know the state of things for the protagonist, the cast of characters, the story world, and the audience at the end of the tale, and the state of things at the beginning of the tale. The greater the contrast, the better. Once these two points of reference are known, the author works out the many steps needed to get the protagonist, the cast of characters, the story world, and the audience from one state to the other.

There is a paradox here. The change that occurs is also an expression of new equilibrium. At a very basic level, story structure can be described as follows:

- an external problem (a change in the ordinary world of the protagonist) disturbs the equilibrium of the initial situation

- the disturbance is explored, a struggle ensues in which obstacles must be overcome

- the problem is understood and dealt with, creating a new equilibrium or resolution

So change is all-pervasive in stories, within them in the form of character development, and without in the form of audience understanding. And that is not even to consider the transformational power of telling a story, when the act of telling the story brings about change in the author.

Read here how change is important for every single scene, though we prefer to call them plot events.

Related function in the Beemgee story development tool:

Character Developer

Not developing your story yet? Click here: