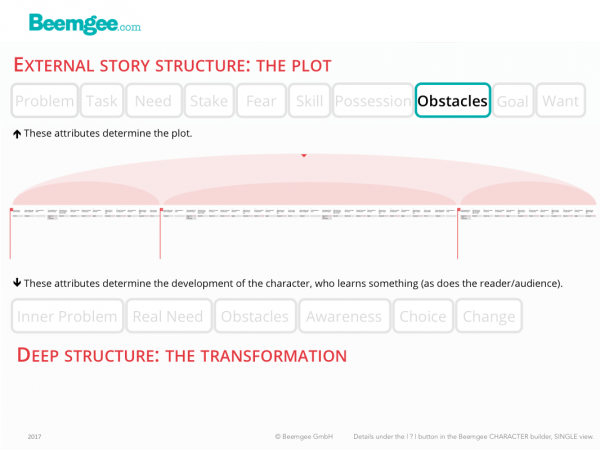

External Obstacles

In essence, there are three kinds of opposition a character in a work of fiction may have to deal with:

- Character vs. character

- Character vs. nature

- Character vs. society

However, this way of categorising types of opposition is not equivalent to internal, external and antagonistic obstacles. Any of the three kinds of opposition listed above may be internal, external, or antagonistic. It depends on the story structure.

External opposition

In any story, the cast of characters will likely be diverse in such a way as to highlight the differences and conflicts of interests between the individuals. In some cases, certain roles may be expected or necessary parts of the surroundings, i.e. of the story world. In the story of a prisoner, it is implicit that there will be jailors or wardens, whose interest it will be to keep the prisoner in prison, which is in opposition or conflict with the prisoner’s desire for freedom. In a jungle story, one may expect wild animals or other natural forces to hinder and obstruct the character in her or his story journey, i.e. in the way towards the goal this character has set. In both cases, in terms of dramatic structure, the obstacles are external to the character.

However, when the force of opposition becomes concentrated and specifically in opposition to the plan and goal of the protagonist(s), then it manifests itself as antagonism. Warden Samuel Norton in The Shawshank Redemption is not incidental or external, but is the main antagonist. In Deliverance, the river down which the characters canoe is not simply part of the story world, but is the representation of antagonism. Similarly, in The Revenant, nature as a force is antagonistic when it is working in opposition to what the character played by Leonardo DiCaprio wants (survival, for a start). Kafka in The Trial or in The Castle set up whole societies which for the characters stuck in them are antagonistic.

So, external obstacles arise out of the story world, not out of the character’s emotional makeup or dramatic function. Internal obstacles on the other hand are inherent in the character. Antagonistic obstacles at their best are aspects of the character’s dark shadow or polar opposite.

External Obstacles are generally part of the story world, not of the character.

External obstacles are more important to the plot than to the inner transformation of the character. Stories that rely heavily upon external factors to provide opposition do their best to load these obstacles with significance within the story world. In Lord Of The Rings, the heroes must overcome several topographical elements, such as mountains and marshes. J.R.R. Tolkien provides all sorts of hints and information about these features of the landscape long before the characters reach them, setting them up as forces of opposition to such an extent that they almost become antagonistic in themselves.

Ultimately, the boundaries between the kinds of obstacles are fuzzy – and in fact it is not so very important to be able to categorize them neatly. What is important is that the obstacles do provide real opposition to the character’s plan. Moreover, by overcoming an obstacle – or indeed by failing to –, the character must be a step further along her or his path of development.

Characters dealing with obstacles and opposition is what makes up the bulk of any story. In a narrative, each obstacle – whether it be external, internal or antagonistic – must be greater in intensity than the last. Ideally, the character will learn through having to deal with each one, and be better equipped to deal with the final great confrontation towards the end of the story. It is unlikely that this great final obstacle that marks what is often called the crisis will be an external obstacle. It is far more likely to be antagonistic, and at best may involve elements of external and internal opposition, uniting all the kinds of opposition in one great climax.

A potential writer’s trap in the external problem is what is sometimes referred to – in a considerable extension of John Ruskin’s original sense of the phrase – as the pathetic fallacy. Sometimes external forces are used in stories to highlight particularly dramatic moments or conflicts. The classic example is a thunderstorm that happens to occur at a moment of great emotional intensity. This sort of convergence of obstacles or forces of opposition runs the risk of turning into cliché.

Now read about:

Related function in the Beemgee story development tool:

Character Developer