How to achieve meaning in stories

What does meaning mean? When is a tale meaningful? A few perspectives on imbuing your plot and characters with a subtext.

It’s no mean feat to make your audience feel they have learned something through your story.

Meaning is that which is intended or understood. The audience draws significance, relevance or profundity out of a story when it understands the deeper implications, reasonings and causes behind it. The meaning of a story depends on the standpoint. An author may mean something different from what the audience understands.

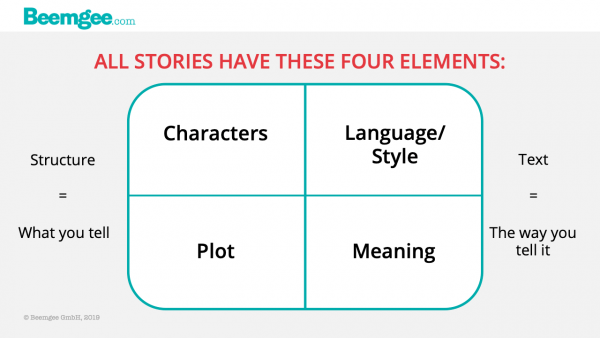

Let’s try to unravel this tricky but essential element of stories. We have noted that stories cannot help but exhibit four distinct elements:

- Characters

- Plot

- Style (aka language, or “voice”)

- Meaning

The interplay of characters and their actions form the plot, and all this is brought into a story structure, or narrative. Since there is always an author writing the novel or a team of people making the film, their stylistic choices determine the language of the work. In this post, we’ll skim the surface of the fourth element. Meaning is, of course, a broad term for something very hard to pinpoint.

We could add more story elements to the list. For instance, we have claimed that there is No Story Without Backstory. Furthermore, since the characters act within a time and place, there is always a story world. And in order to make the audience understand all this, there is always some measure of exposition. Then there is change or transformation, cause and effect, etc.

Let’s break down how we might look for the meaning of a story.

Academic Approaches

- For a start, there is the author’s intention as one frame of meaning. What was the storyteller trying to tell us? What did the writer mean by choosing exactly those words? What did the director want to get across with these particular images and sounds?

- Then there is the interpretation the recipient brings to bear. How does the reader or viewer understand the story? This can be based purely and solely on the work, where only the text of a novel (or the interplay of images and sounds of a film) is analysed and interpreted.

- Another approach is to examine the way a work is understood in a broader context. The meaning the work generates may be influenced by what is known about the author or the culture the work springs from. Parallels may be drawn to other works. That is to say, a work can be analysed in the context of the time and place it was produced and understood in relation to other works and to history.

All three are typical academic approaches to stories, while the third seems to be the most widespread.

While many ways to glean meaning from stories do not make as sharp a distinction between text and content as we do at Beemgee, innovative techniques of telling a story tend to excite professors of literature more than classically crafted tales told in modes that are established. Stories told in such a way that they push the boundary of familiar modes, genres or media tend to be considered more “meaningful”, at least in the history of particular media, such as the novel. So labels such as “literature” or “art” are more quickly bestowed on works that are less accessible because the authors are experimenting with unfamiliar techniques. Once these techniques become familiar they typically get a name ending in -ism, such as “post-modernism” or “magical realism”. And once the techniques are used by the mainstream or become very popular, academics no longer consider new works created in such a mode particularly artistic.

Industry Approaches

Also, what we are getting at with the term “meaning” has implications for the publishing or entertainment industries. At Beemgee, we consider differentiating between “commercial” versus “literary” fiction somewhat spurious. We are not concerned with terms such as mainstream versus arthouse. Hopefully our outlining tool and our articles on storytelling will convey that dramaturgy is equally important wherever in any such spectrum a story may be positioned.

We can divulge, however, that typical of the “commercial” or “mainstream” end is that the audience is not made to work as hard. Much “literary” or “arthouse” fiction is that because it is less direct, less obvious in meaning. It makes the audience work harder in that it poses more riddles. Rather than saying everything there is to know about the story or a scene outright, the authors may veil what is actually going on, giving hints and pointers rather than spelling things out. Pre-interpretation or direct statements of theme are avoided. Mainstream is easy to consume. Art challenges the audience to understand.

As a simple example, here is the opening line of The Sound And The Fury: “Through the fence, between the curling flower spaces, I could see them hitting.” William Faulkner deliberately chooses not to explicitly tell the audience that what is being described here is a game of golf. On the contrary, the word hitting misleads the reader because it connotes and even denotes violence. That it’s only about golf is a piece of information that the readers must work out for themselves through other clues given on the first page, such as the words “flag” and “caddie” (where Caddie, it soon transpires, is also the name of a character). Certainly it would have been quicker, so the reader recognises the action being described, if Faulkner had used the word golf. However, the opening pages achieve that the audience understands more about what the point of view character Benjy sees than he does himself, and learns about Benjy’s mental state. None of this is directly relayed. It is all in a form of code. The author’s choice of words determines meaning.

So “arthouse” and “literature” encodes stories and plot events more than commercial mainstream fiction might. Nonetheless, dramaturgy – the crafting of narrative – is no less relevant for such “encoded” stories. In novels like Nabokov’s Lolita or Faulkner’s The Sound And The Fury, the structures of the stories themselves – i.e. what the characters do when and why – are consciously composed rather than left to chance.

The degree of encoding in the telling of the story may determine how the publisher of a novel or the distributor of a movie chooses to package the product, as arthouse or commercial.

Beyond accessibility, on the level of subtext: Something that we know already feels less meaningful than a freshly experienced revelation or newly made epiphany. Hence original works are more likely to be considered art than derivative stories. Art takes us out of our comfort zone. It provokes people by disregarding conventions, pushing the boundaries of what is known or generally accepted, by breaking norms and taboos. Mainstream, on the other hand, confirms norms and reinforces widely held ideas, beliefs or views by reiterating standards in ever recurring variations (consider for example typical “damsel in distress” stories). Mainstream remains within the framework of what we typically think and feeds us the comfortable feeling that what we believe is indeed right and correct. Art jolts you into reappraisal.

It should be clear that art does not preclude commercial success. An original or creative work can be a bestseller or blockbuster. For example the movie Matrix pushed many boundaries, surprising audiences with philosophical ideas in an action movie full of new visual techniques and having the damsel rescue the male hero at his low point.

Individual Approaches

Whenever any individual is sucked into experiencing a story, probably a mixture of all the above takes place. In addition, there are all the associations this individual brings to bear. If you are reading a novel or watching a movie, the arrangement of words in a sentence or the composition of an image might resonate within you or remind you of something, consciously or unconsciously. Your brain will start to make connections unique to you, beyond any authorial intention.

These associations can be cultural or they may be utterly personal. It is difficult if not impossible to be sure how much of which is at play in any given association. To an American, we may hypothesise, the image of the American flag will awaken somewhat different associations than, for instance, to an inhabitant of Indonesia. This is a cultural aspect. On the other hand, a love story might awaken memories of “the one that got away”, or a fight scene might remind one of a punch-up you once had at school, and these are totally personal memories.

So there are layers of meaning that are specific to each member of the audience, and that are pretty much beyond the control of the author.

Note, however, how such layers of meaning seem to be evoked by the story in each recipient through the emotions they feel. So meaning is not necessarily as rational as we might like to think.

Meaning in Narrative

One more thing.

The diagram above seems to suggest that meaning is separate from the other three components, language, plot, and character. This is misleading for three reasons:

- As we have seen with the Faulkner example, meaning can be created by precise control of language.

- Secondly, a work as a whole tends to treat at least one theme. Theme is a bearer of meaning. It is achieved through the overall arrangement of the story, i.e. the composition of language, plot, and character.

- Finally, narrative is the arrangement of plot events into a form or structure that carries meaning. Narrative demonstrates causality. In between each plot event of a narrative you could place the words “because of that …”. If the cause of each scene is a preceding scene, and each scene determines how subsequent scenes are understood, then plot can be considered a motor of meaning.

So meaning is like conflict in that it soaks through stories, filling a story up in an all-pervasive way. It is unlike conflict in that it is impossible to write a story which has no meaning at all, while it may, at least in theory, be possible to write a story which has no conflict.

Deliberate and conscious

Authors are concerned with the conscious composition of dramatic narrative. By arranging character actions, structuring plot, and determining theme authors and storytellers convey meaning. Ultimately though, meaning is in the mind of the beholder.

Want to create a meaningful story?