Why It’s Important to Understand Cause and Effect When Plotting Your Story

By Lucia Tang.

Lucia is a writer with Reedsy, a marketplace that connects authors with editors, designers, and marketers. In Lucia’s spare time, she enjoys drinking coffee and planning her historical fantasy novel.

Whether we’re piecing together the timeline for a homicide or puzzling out the intricacies of Newtonian mechanics, cause and effect are crucial to how we make sense of, well, everything. Of course, I say “we” loosely. As writers, most of us won’t actually be catching killers or solving the coefficient of fiction. But still, stories are no exception to this rule: without cause and effect, they fall apart.

At the end of the day, writers should have as tight a grasp on causality as any detective or physicist. It doesn’t matter if you’re working on a doorstopper to rival War and Peace, or a breezy picture book for baby bookworms: you’ll need to craft a storyline that makes sense. This makes your readers want to spend time in the world you’ve created — and ensures they’ll leave it feeling enlightened and satisfied.

Of course, you can get there haphazardly, writing juicy scenes as they come to mind and attacking the chaos of your draft with a merciless red pen. But if you want to save time during the editing process, keep cause and effect in mind as you plot.

Let’s try that process for a hypothetical novel, a quirky romance called Heart of Moss with a randomly generated plot. Our heroine, Princess Felicienne, grows attached to a hitman, codenamed “Moss,” who spends most of his time — when not assassinating the rich and powerful — as a mild-mannered florist named Alan Gill.

Ensuring the reader’s suspension of disbelief

Your readers might be razor-sharp connoisseurs of plot — the type who can spot a twist from a mile away and catalogue the clichés on every page with a sneer. But your job as a storyteller is to make them forget all that. You want to enthrall them so deeply they can’t do anything but turn the page, reading compulsively with slack-jawed awe.

Readers should approach your book as fans, not critics. The second they switch their brains to reviewer mode, you’ve already lost them. One guaranteed way to do that? Disrupting their fragile suspension of disbelief by introducing plot points from seemingly out of nowhere.

Remember Game of Thrones’ much-maligned last season? The conqueror-queen Daenerys spent much of her considerable screen-time insisting she refused to be a “queen of the ashes,” presiding over a wasteland of war dead and charred ground. But just when the city she strove so hard to take signals its surrender, she turns around and sprays it with dragon-fire.

There’s been lots of ink spilled on Daenerys’ apparent turn to the dark side, and maybe that’s a storytelling success in its own right. But as a plot point, there’s no denying it didn’t work for a lot of viewers. This unsatisfying plot twist forced them to step back from the story and watch the footage at a distance — as critics. That’s because the dragon-queen’s rampage seemed out of left field, an effect with no discernible cause.

Using Beemgee to keep track of cause and effect

Let’s try our hand at plotting out Heart of Moss without falling into Daenerys Syndrome, as we might call it. Our plot generator provided us with an opening: a meet-cute at a baseball stadium. A downpour furnished a perfect excuse for two strangers with great chemistry to get close to one another, huddling under the same umbrella.

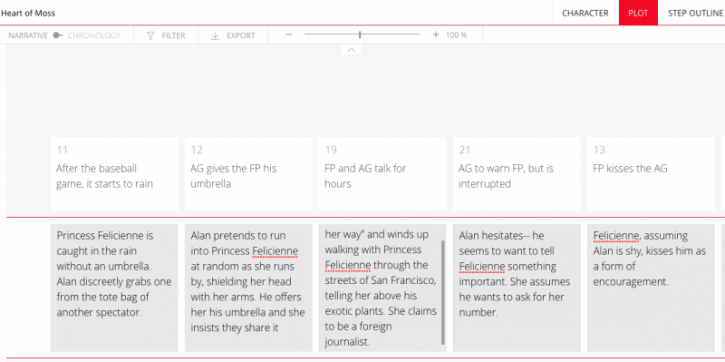

Beemgee’s Plot tool allows us to organize our story in narrative order: that is, the order in which it’s told. So let’s enter these first few plot points:

This setup is cute enough, but it’s also pretty implausible — even by the standards of a light, romcom-style read. How exactly do a princess and a hitman end up together at a baseball game, with enough privacy to end up on a quasi-date? What is the cause — or causes, plural — behind this seemingly bizarre set of circumstances?

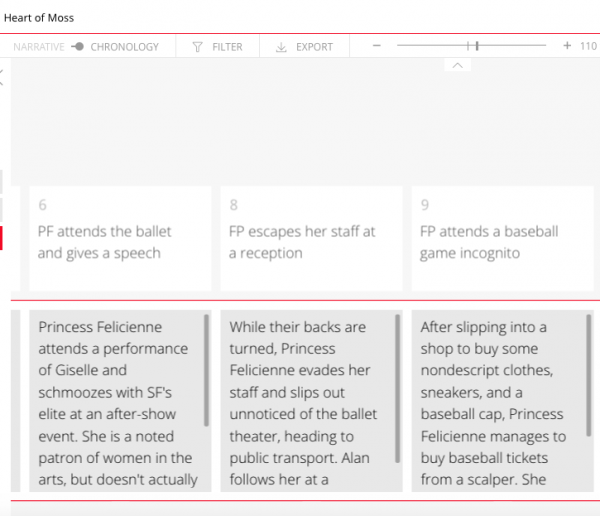

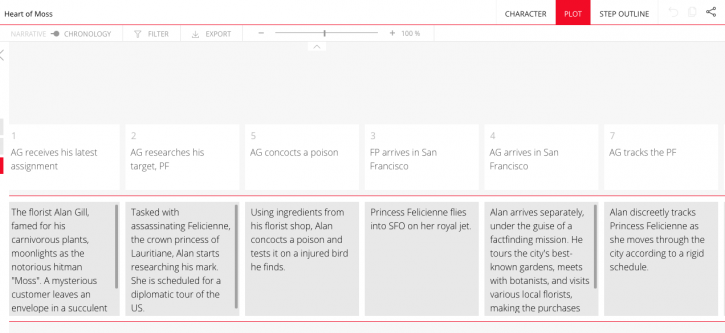

To figure that out, we’ll need to determine what happened before this rain-soaked meet cute. So let’s toggle over to Beemgee’s chronological view. This lets us order events according to when they happen, regardless of any flashbacks and flash forwards. How did Felicienne, a princess presumably supported by an enormous royal staff, end up at a baseball game unsupervised, without an umbrella?

And what about Alan? A hitman, cozying up to a foreign dignitary, feels awfully suspicious, even if she lied to him about her identity. Did he really offer her his umbrella because he thought she was cute, or did he have an ulterior motive? What was the actual cause behind his presence in the stadium?

When we return to the narrative view, we can decide when, in the story, to reveal that sweet-natured Alan, with his handy umbrella, is also the notorious hitman Moss. Do we clue the readers in before or after Felicienne herself finds out?

Either way, the cause and effect behind Alan’s appearance in the stadium should remain unchanged — and that should color how we write the scene. Even if we hold back some of the truth, we can’t make Alan do anything that will outright contradict the fact that he’s secretly also a hitman. If we do, readers will be frustrated when they reach the reveal.

By toggling between the chronological and narrative views, it’s easy to ensure that a story is plotted with impeccable causality, even if it’s told in an order that keeps the characters — or even the audience — in the dark. That way, your readers can enjoy your story as fans instead of critics, no matter how many twists you throw their way.

Ready to try the tool for your own story?