The Differences Between Authoring and Writing and How to Author a Story

Today’s guest post is by author Stefan Emunds.

Today’s guest post is by author Stefan Emunds.

Stefan’s favorite genre is visionary fiction – stories that have an enlightenment dimension. Enlightenment and storytelling have interesting parallels, which prompted Stefan to write a book about storytelling – The Eight Crafts of Writing.

Get a glimpse of his approach to story craft in his article.

Art and Craft

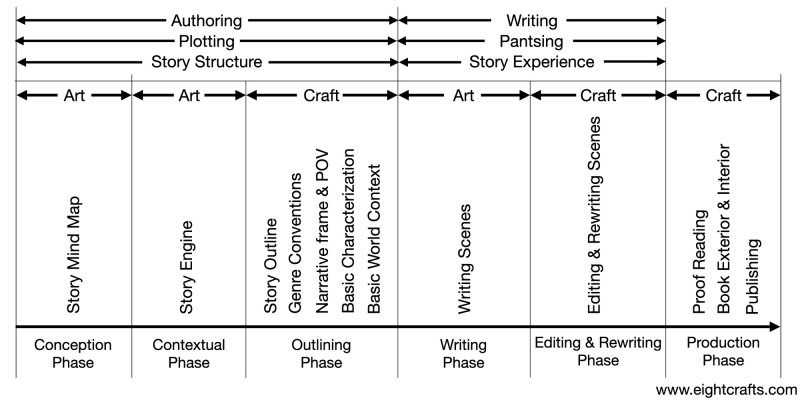

Storytelling is both art and craft, authoring and writing, plotting and pantsing.

1.1 Art and Authoring

Art is creativity. Creativity requires receptivity to the Muse and its inspirations.

Inspirations arrive as thought-images, which writers put into words. How to turn thought-images into words and assemble those into a structured story with vivid characters and an engrossing world is a matter of craft and skill.

1.2 Craft and Writing

The literal meaning of Kung Fu is a discipline achieved through hard work and persistent practice. Writing is Kung Fu.

Craft gives form to inspirations. Forms limit. Writers love the artistic side of writing, less so crafting, in particular, Story Outline. Writers are prone to procrastinate crafting.

But no limitations, no story. No canvas, no painting. No net, no tennis.

Understanding the difference between freedom and dominion helps to appreciate the constraints of craft. Freedom is a means to an end. We want to be free to do something, for example, to write a book. That’s all there is to freedom. Dominion, on the other hand, is mastery of structure.

1.3 The Authoring and Writing Phases

If a task is too complex, break it down into a series of small and manageable tasks. Allow me to break down storytelling into the following stages and phases:

In this article, we will have a closer look at the authoring stage.

2. How to Author a Story

The authoring stage comprises three phases:

- The conception phase

- The contextual phase

- The outlining phase

2.1 The Conception Phase

The Muse seduces a writer and gets him pregnant.

We conceive inspirations as fragments, or rather puzzle pieces, for example, an interesting what-if, the image of a quirky character, a cool inciting incident, a mind-blowing scene, or a riveting dialoguefragment.

Why don’t you capture those inspirations in a story overview? A story overview is a drone view of the most important story elements:

- Adversity

- Antagonist

- Protagonist

- Inciting incident

- Stakes

- Story goal

- Midpoint

- Key ability

- All-is-lost moment

- Climax

- Conclusion

You could summarize your story elements in a word or two and jot down additional thoughts below them.

The story elements make up your story engine. Upon completing and assembling your story engine, your story will run, meaning it will write itself.

2.2 The Contextual Phase

The purpose of the contextual phase: Finding the missing story elements.

While the first inspirations for your story came uninvited and effortless, requesting targeted inspirations from the Muse is a hard earned skill. Let’s call this skill focussed meditation. Focussed meditation synchronizes focus and receptivity, in this case the focus on a missing story element and the receptivity to the Muse.

The problem: During focussed meditation, subconsciousness will remind you of things you experienced, read in books, or watched in movies, things that aren’t original. Likely, you will have to ignore ten such memory diversions to receive original ideas. Some professional authors collect up to twenty options for each story element before choosing one.

Completing the story engine can take weeks, if not months. A notoriously difficult item to nail is the climax. Mind that many literary works that excel in prose and drama lack inspiring climaxes.

Sometimes, you won’t be able to hear the Muse. In this case, you need to fall back to your reservoir of personal experiences, books you read, or movies you watched and innovate or steal something. This is perfectly fine, and every artist does that.

Good artists copy. Great artists steal.

– Pablo Picasso

Great artists steal. They don’t do homages.

– Quentin Tarantino

2.4 The Outlining Phase

The tasks of the outlining phase are:

- Deciding on a genre

- Deciding on a narrative frame and/or POV)

- Accomplishing basic characterizations and world building

- Outlining the scenes

2.4.1 Genre

Genre manages readers’ expectations.

Stories have external and internal genres. Examples of external genres are thriller, romance, and adventure.

Examples of internal genres are redemption, education, and revelation.

2.4.2 Narrative

Narrative comprises three things:

- The author’s voice

- The narrative frame

- The POV

A narrative frame determines the angle from which a story is told: why, to whom, and when. For example, a narrative frame could be an interview or an interrogation. Epistolary novels and fictional diaries are narrative frames.

Persons can be narrative frames too, for example, Dr. Watson in The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. In such cases, the narrative frame and POV overlap.

2.4.3 Basic Characterization and World Building

Usually, the story world and characters reveal themselves while writing. But some characterizations and world building elements impact story outline, for example, the protagonist’s flaw and motivation determine the story’s midpoint. If you nail them prior to writing, it will help with the first draft and reduce the danger of rewriting.

An example of a world building element that affects story outline is the story world’s power structure that the protagonist and antagonist need to navigate.

2.4.4 Story and Scene Outline

The next step is structuring your story according to story outline principles and genre conventions.

For that, you can use the Hero’s Journey, the Virgin’s Promise, Robert McKee’s Five Commandments, or other story outline methods.

The key scenes from your story’s outline and the key scenes of the story’s genre will give you fifty to sixty scenes to write, et voilà, you got your story’s skeleton.

3. Take Your Time Authoring

In his book Story: Style, Structure, Substance, and the Principles of Screenwriting, Robert McKee suggests that successful screenplay writers spend two-thirds of storytelling time on authoring and one-third on writing.

In the case of fiction, the ratio is probably something like 50/50. Literary fiction writers need to demonstrate exceptional prose and may end up with 30/70.

This ratio is a time ratio, not an effort ratio. Let’s assume your story takes twelve months to write. This means that you will spend six months on authoring your story. Likely, you will author just an hour or two every day, sometimes not at all for a couple of days. While it takes six months to author your story, you may have only worked on it – accumulated – forty-five days. While the time ratio of authoring/writing is 50/50, effort-wise it is something like 20/80.

What to do with all that free time? You can promote your published books. Or you can author a new story while you are still writing your current one.

The Writing Phase

Sit at your laptop and bleed your fifty to sixty scenes.

Apply Stefan’s ideas to your story: