The Evolution of Cause and Effect and the Cooperative Principle in Storytelling

Some theorists have posited that stories are all about problem-solving. And certainly – as we have seen – problems are at the very core of story. So by giving the audience a chance to vicariously experience protagonists dealing with problems, a story is in effect a sort of playground or simulation where we can experience what potential problems and solutions feel like – but without any real-life consequences.

An important consideration here is cause and effect. In real life, what we experience has so many causes that it is well-nigh impossible to accurately pinpoint them all. We constantly feel the effects, but it’s hard to pinpoint all the causes. Nonetheless, we really like to have explanations for what’s going on, it gives us a greater sense of control over our own lives. As a species, we seek agency, we’re always looking for what caused something to happen, for the why behind things being as they are. We find it very confusing when we don’t know the reason for the events we live through, and we build elaborate mental constructs to explain to ourselves the world as we perceive it. In this context, we sometimes speak of “narratives”.

In stories, every scene must be the result of a preceding plot event. As we have said before, in between each plot event of a narrative you should be able to place the words not “and then”, but “because of that …”.

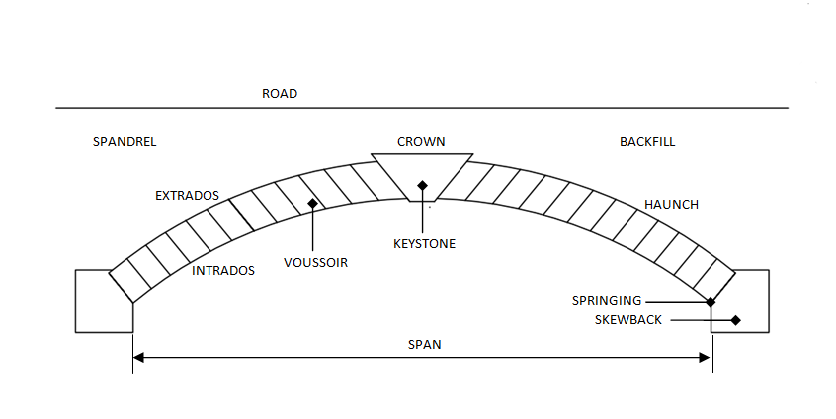

Each scene has a raison d’être; it tells the audience something new and moves the story forward. As a consequence, the story develops into an arc of cause and effect. Think of it like one of those Roman bridges. Every slightly tapered stone is chiselled to fit exactly into an arch, and all of the stones hold each other up.

Source: http://3.bp.blogspot.com/bridge.pngTake one scene/stone away, and the whole bridge/narrative becomes wobbly or collapses. Change the form of one scene/stone and you have to make adjustments to some or all of the others.

We have shown this image before as part of our explanation for why crime fiction is so popular. The point we’re repeating here is that stories exhibit cause and effect somewhat more than real life does. Therefore stories appear to make sense to us, and that means stories are satisfying – and comforting. They seem to teach us that “if we do something like this, then a potential result is something like that”.

Through the cause and effect pattern of stories we see potential outcomes of behaviours. For example, excessive pride leads to a fall. So the playground of story is, like real playgrounds, a space for learning.

What do we learn?

“The moral of the story is …” invariably about how self-centred or egoistic behaviour is bad whereas cooperative and selfless behaviour is good – for the character and for the community in which the character lives, and by extension for us and our community and society. This principle holds true for almost all stories, and if in a specific case it feels like cliché then the story was probably executed in a heavy-handed manner.

Why is this cooperative principle an almost universal trait of stories?

Because at root the whole reason why storytelling exists is because it teaches us humans about living together in a group. Social behaviour of group members helps a group or community (a clan, a tribe, a culture or a herd) to survive and thrive, whereas selfish and anti-social behaviour has negative effects for the well-being of the group.

There is, of course, no need to be clichéd and trite – as an author you don’t want to ladle out the moral too thickly. But these are the underlying reasons why the transformation of a character is the emotional keystone of so many stories. The flaw or internal problem of a character has anti-social effects – the change in the character’s nature by the end of the story shows the benefit of social behaviour.

And if you’re now thinking, “Wait a minute, what about all those stories in which the main character doesn’t become a better person or the baddy doesn’t get their comeuppance?” Well, cases like this can serve as a negative example. Take for instance Michael Corleone in The Godfather. We are fascinated by this character’s descent into emotional oblivion, and it is revealed at the end how he has not achieved what he intended (to stay out of his family’s mafia business), but on the contrary becomes the new don. We learn how easy it is to make mistakes that lead to awful consequences. Michael’s decisions (to protect, to avenge) were causes of the end effect of his losing his wife and perhaps his humanity. The lesson to the audience is conveyed by negative example.

Authors turn such character issues into plot events and shape these events to show transformation, making sure there is plenty of contrast between the characters. Contrast is important because it provides the potential for conflict. So authors try to give each character different internal problems, needs, etc.

All this is something to bear in the back of your mind when developing characters and composing your plot.

Photo by Bradyn Trollip on Unsplash

Arrange your story: