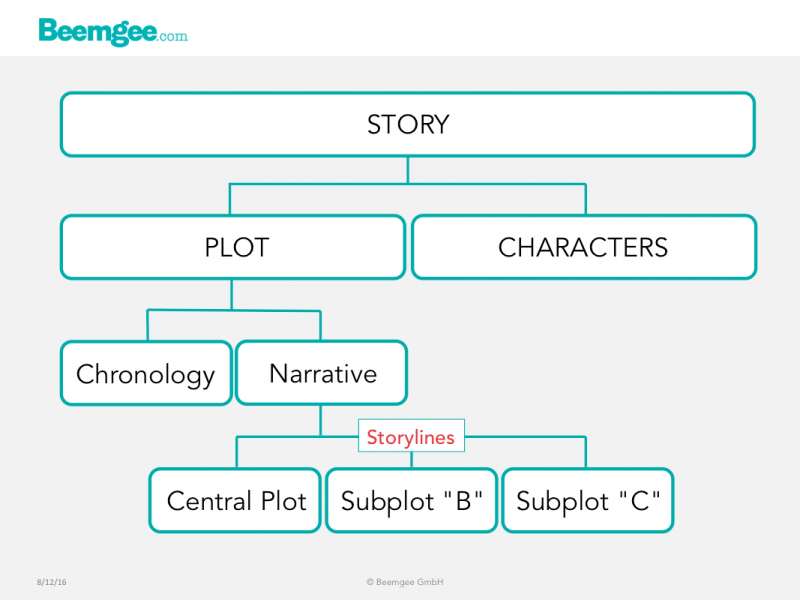

Storylines

A plot arises out of the actions and interactions of the characters.

On the whole, you need at least two characters to create a plot. Add even more characters to the mix, and you’ll have possibilities for more than one plot.

Most stories consist of more than one plot. Each such plot is a self-contained storyline.

The Central Plot

Often there is a central plot and at least one subplot. The central plot is usually the one that arcs across the entire narrative, from the onset of the external problem (the “inciting incident” for one character) to its resolution. This is the plot that is at the forefront of the story, on its most obvious, visible and therefore external layer. For instance, the central plot of a crime story traces the events to do with the detective solving the case. In an adventure story about the search for a treasure, the chain of events from the moment the treasure is first mentioned to its being placed in its final destination is the central plot. That’s why the central plot is often what a story is described as being about.

Subplot – The Love Story

There is likely to be at least one subplot. Classically, this begins around about the time the protagonist commits properly to the central plot – by devoting him or herself to solving the case or finding the treasure. In other words, once the hero has set off on the story journey. At about this point in the narrative, a particular character may appear or become suddenly more relevant.

Initial conflicts notwithstanding, this new interest is ultimately likely to help the protagonist on an emotional level. The conflicts and obstacles to be overcome may be hindrances that arise out of misunderstanding, rather than out of antagonism. And they may come to a head at a final moment of dilemma, where the protagonist has to make a moral choice which will have direct consequences for the central plot.

Though prone to cliché, this plotline has a vital role in making the story as a whole work, because it shows the protagonist growing as a human being, i.e. developing into a mature, self-aware and socially fully responsible person. This classic plotline is the love story.

Subplot – The B-Plot

If you look at TV series, especially the now somewhat old-fashioned type where each episode is a self-contained story (think sitcoms like The Simpsons or shows like The A-Team), you’ll notice that they almost invariably feature two parallel stories, the central plot and the B-plot. This design principle has several functions. For one thing, the viewer is less likely to grow bored – the variation creates liveliness and allows the authors to place cliffhangers. Having a B-plot also creates possibilities for contrast and juxtaposition, which makes for satisfying effects such as irony or humour.

The Power Of Four

The convention of telling a second plot “under”, or rather intertwined with, the central plot also has a lot to do with the power of four in storytelling. You may have observed that innumerable stories are built around four main characters – for example The Simpsons, The A-Team, Sex and the City, Stand By Me, When Harry Met Sally, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, and many more.

Constructing a story around four characters is by no means a rule, but it automatically entails that you have several parallel sets of relationships going on. In terms of scenes, while character A is interacting with character B, character C is free to interact with character D. This allows for “cross-cutting” effects to achieve interesting contrasts, variation and juxtaposition.

We’ll go into the reasons why the power of four is so pervasive in storytelling elsewhere.

Storylines And Plot Structure

In particularly well-crafted stories, each storyline echoes the others, for instance by treating the same overarching theme but showing it in a different light, from another perspective. If, for example, the theme is about the necessity for reform, then one plot may concentrate on the political reform of an organisation while another plot shows the reform process of an individual.

Furthermore, each storyline must go through the stages common to all plots. That is, a storyline must cover the entire range from the advent of a problem through commitment to the attempt to solve it, the task which arises out of that commitment, the story journey towards the goal with the aim of getting to the circumstance, situation, or state that is wanted, but first having to overcome various obstacles, and possibly having a moment of revelation leading to a learning effect. So a subplot may be less intricate than a central plot, but structurally it works along similar lines.

When children tell stories, they tend to string events together with “and then”. However, far more important than narrative sequence is the reason for the sequence. When you shape your story, put all the events of one filtered out storyline into the narrative order and link each causally. String the events of a storyline together with “because of that” instead of “and then”.

Subplot storylines are most satisfying when they cover the course of the story at roughly the same pace as the central plot, and overlap with it a key moments. When done really well, the final resolution will be one single plot event which brings each storyline to a conclusion. If that is not possible, then the subplots will come to their resolution very shortly after the climax of the central plot.

To give the protagonist’s main story, the central plot, depth, it pays to add other issues for her to deal with. These can be personal or family conflicts, or troubles typical to a particular phase of life that the character happens to be in (but heightened), or some sort of mystery as a recurring motif or even a running gag. Whatever it is, it should be established early in the narrative and carried through to the end.

Another idea is to create other characters going through some sort of parallel storyline. Here again the subplot should be established early, and in order for the audience to care about it be connected somehow (for instance through locations or combined scenes) to the central plot. If it is completely disconnected, it is harder for the audience to understand its purpose. Even if such a separate storyline is set in a different time or place with no direct connection to the main story, then parallels or juxtapositions should make clear why it is there. In the best case, the storylines support each other, increasing the audience’ interest in both.

Related function in the Beemgee story development tool:

Storylines